This is the second part of a two-part series. Part 1 examined the ecosystem and watershed joys of beavers. Part 2 examines the economics of using beavers to both mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Figure 8. Beavers are a family-friendly species. Source: Oregon Historical Society.

Beaver Potential for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation

Humans must address human-caused climate change through both mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation means eliminating human-caused emissions into the atmosphere of carbon dioxide and other global warming gases. It also means removing excess CO2from the air and putting it safely back into vegetation and soil. Beavers (Figure 8), by creating wet meadows that have lots of organic material, help sequester carbon in the ecosystem. As one example, in the Rocky Mountains a study found that dried-out beaver-created meadows contained 8 percent of total organic material in the landscape, while wet meadows—still wet because beavers were on the job—contained 23 percent of the total organic material.

The other side of climate change is adaptation. Western North America is losing its glaciers (Figure 9) and snowpacks due to a warming climate. Late-season stream flows in autumn—the most important flows of the year because they are scarce—will get scarcer. To provide for more late-season stream flows, some will propose engineering solutions of primarily concrete dams (Figure 10). Instead, we should rely on another kind of engineering solution. Yes, it still involves dams—many, many more than those that might be made of concrete—but these dams would be made by beavers, using locally sourced materials.

Figure 9. From the cover of the Oregon Global Warming Commission Biennial Report to the Legislature 2017. The late great Oregon photographer Gary Braaschtook these photos of Oregon’s Mount Hood in the late summers of 1984 (bottom) and 2013 (top). It’s not a case of a bad snow year but rather a bad glacier century. Original source: Braasch Environmental Photography.

Figure 10. An example of a bad beaver dam is the US Army Corps of Engineer’s Beaver Dam in Arkansas.Source: Christopher Ziemnowicz via Wikipedia.

We Need Millions of New Dams!

That’s right, the best way to adapt to less instream water due to climate change is to build new dams—millions of new dams! However, to keep the fiscal and economic costs down and the coincidental environmental and social benefits up, every one of these new dams needs to be made by beavers. A few of these dams may be quite large (Figure 11), but most will be modestly sized (Figure 12) and strategically placed, as beavers know best.

Figure 11. At ~850 meters in length, the world’s largest known beaver dam is in Alberta in Wood Buffalo National Park.Source: Parks Canada.

Figure 12. An example of a good beaver dam that is modestly sized. Source: Wikipedia.

Can Beaver Dams Replace the Lost Runoff from Melting Glaciers and Snowpacks?

Professor Joe Wheaton of Utah State University has developed a Beaver Restoration Assessment Tool (BRAT) in which watersheds at any scale can be modeled as to their potential for beaver restoration and all of the benefits that go with it. Macfarlane, Wheaton, et al. (2015) identified the following parameters that are important for successful beaver dams:

(1) reliable water source,

(2) riparian vegetation conducive to foraging and dam building,

(3) vegetation within 100 m of edge of stream to support expansion of dam complexes and maintain large colonies,

(4) the likelihood that channel-spanning dams could be built during low flows,

(5) the likelihood that a beaver dam can withstand typical floods,

(6) a suitable stream gradient that is neither too low to limit dam density nor too high to preclude the building or persistence of dams, and

(7) a suitable river that is not too large to restrict dam building or persistence.

Can enough beaver dams offset all the loss of runoff from melted glaciers and missing snowpacks? In some places yes, in some places no. In all places, somewhat to a lot. It’s worth doing in any case because whatever the increment of downstream flow, it’s a very cheap way to obtain/regain such flows and it also provides all those onsite ecosystem and watershed services.

Where beavers cannot totally offset the upstream losses of water (and even where they can), it is time to dial back the downstream wastes of water. Most municipal, industrial, and agricultural water users all waste water because it is too cheap to the consumer. Do we really need to grow cotton and rice in a desert? How about lining those irrigation ditches? How about drip irrigation? How about banning overhead sprinklers? How about fully recycling sewage effluent? How about dialing back on those lawns appropriate in the British Isles but not in arid climates? How about water-efficient domestic water fixtures? None are a silver bullet, but all (and more) are silver buckshot.

Goodbye Cows and Loggers, Hello Beavers

Throughout much of the arid American West, if beavers are to be brought back in a big way, domestic livestock will have to give way. A native species, beavers are known as nature’s engineers for their ability to positively affect ecosystems and watersheds. An alien species, domestic livestock are known as nature’s annihilators for their ability to negatively affect ecosystems and watersheds.

The damage to streams from the loss of beavers has been exacerbated by the introduction of domestic livestock. For beavers to do their job and make their best dams, there must be adequate large vegetation in the landscape. A cow-bombed stream has little riparian (streamside) vegetation due to heavy livestock use, and no large shrubs and trees out of which to make a proper dam.

On public lands, livestock grazing could be equitably ended. On private lands, grazing rights could be obtained to welcome back beavers. Better yet, such private lands could be acquired from willing sellers and reconverted to public lands so as to provide a full suite of ecosystem, watershed, and recreational services.

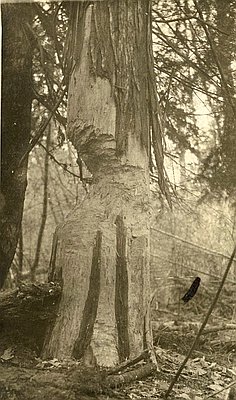

The best beaver dams have lots of large woody debris, which often comes from beavers converting large wood (a.k.a. trees) into debris. Willows and cottonwoods, both deciduous riparian species, make good beaver dam material, but so do conifers (Figure 13). Conifers can be valuable for commercial logging; thus there is an inherent conflict. Given the massive watershed, ecosystem, and climate adaptation benefits, and the climate mitigation benefits of bringing back beavers, and give the massive ecosystem, watershed, and climate damage of continuing logging, human loggers must give way to beaver loggers.

Figure 13. Timberrrrrrrr! Source: Oregon Historical Society.

The Solution: Leaving It to Beavers

An ever-expanding human population demanding more water combined with the loss of glaciers and snowpack due to a warming climate means that the further damnation of the American West is inevitable—unless society favors beaver dams and eschews more concrete dams. The State of Washington has identified six new “large storage” dams in the Columbia River basin that would cost (assuming no construction overruns) $2,184–$3,600 per acre-foot of storage, or $1 billion–$8 billion per dam for the largest four projects. Water reuse (drinking our treated effluent) costs $300–$1,300 per acre-foot, while desalination comes in at $2,000–$3,000 per acre-foot.

The estimated cost of one highly planned experiment to reintroduce beaver at three to five sites is $70,000 (or $14,000–$23,000 per reintroduction). Assuming each reintroduction results in 17.5 to 35 acre-feet of “storage,” this pencils out to a weighted average of ~$800/acre-foot. Doing this reintroduction at a large scale will result in significant cost reductions, so it is reasonable to assume ~$200–~$300/acre-foot of storage.

On top of providing relatively inexpensive new water storage, beaver dams, unlike human dams, create wetlands. Wetlands provide critical ecosystem services, which can be measured monetarily. Ecosystem services include flood attenuation, increase in water quality and quantity, recreational and commercial fishing, bird watching and hunting, wildlife habitat, storm amelioration, and other amenities. Economists have valued these services to society at $2,400–$4,800 per acre of wetland per year, which, capitalized at a conservative 3 percent interest rate, results in a net present value of between $80,000 and $160,000 per acre. To mitigate for wetland destruction due to development, a market in wetland credits has arisen, trading at as little as $4,000 to as much as $125,000 per acre.

Beaver reintroduction is increasingly being used at a local level to address water quantity, water quality, fish and wildlife habitat, and other issues, including micro-level adaptation to climate change. However, for a macro-level response—to actually move the needle on the continental water gauge—beaver reintroduction needs to scale up big time. It needs to be a national priority, comparable to creating the Interstate Highway System. However, in this case, it won’t be gray infrastructure but rather green infrastructure. All we need is enough beaver families spread across enough watersheds.

For More Information

Here are a few documents to start with:

• Beaver and Climate Change Adaptation in North America: A Simple, Cost-Effective Strategy. 2011. WildEarth Guardians, Grand Canyon Trust, and The Lands Council.

• Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter. 2018. Ben Goldfarb. Island Press.

• The Beaver Solution: An Innovative Solution for Water Storage and Increased Late Summer Flows in the Columbia River Basin. The Lands Council.