It has long been an ecological and hydrological truth that to save the lower Snake River salmon runs, four Army Corps of Engineers dams on the lower river in Washington State need to come out. A political opportunity may now be arising for a grand bargain that restores the salmon runs and at the same time makes existing economic interests whole or better and helps out federal taxpayers and regional electric ratepayers.

General and President Dwight D. Eisenhower said, “If a problem is unsolvable, enlarge it.” The military genius and Republican president may have first articulated it, but a Republican member of Congress from Idaho is seeking to operationalize this sage advice in regard to Pacific Northwest salmon and electric power.

A Dam(n) Crisis

In 1980, in recognition of the depleted and diminishing salmon runs in the Columbia River Basin and a boatload of other political issues, including but not limited to

• a predicted electricity supply shortage,

• predicted skyrocketing electric power costs,

• threats of California taking our power,

• aluminum companies needing even more subsidized power,

• cost overruns at five nuclear power plants, and

• the Bonneville Power Administration being in crisis,

Congress enacted the Pacific Northwest Electric Power Planning and Conservation Act (NW Power Act). It was a grand bargain in which particular special interests agreed to support the mutual relief of themselves and the other special interests. Also, the public interest in fish and wildlife was then to have “equitable treatment” with power, navigation, flood control, and other purposes of the Columbia River Basin system of electricity-producing, flood-controlling, and barge-floating dams (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Some dams block salmon migration. Others that don’t block it nonetheless lethally impede both upstream returning adults and downstream juvenile migrants. Source: The Economist.

As far as electric power planning and conservation, the NW Power Act has worked splendidly. As for fish and wildlife, some useful mitigation for losses associated with the dams has occurred (Figure 3) (more useful generally to wildlife than to fish). As that member of Congress from Idaho recently noted: “The salmon recovery efforts that we have been engaged in so far have probably kept the salmon off the extinction list.” But has the treatment been “equitable” with other uses? No.

Figure 3. Fish ladders only work, and not all that well, to pass returning adult salmon upstream past a dam. Source: Save Our Wild Salmon.

Five times, federal court judges have rejected the “biological opinions” issued by NOAA Fisheries pursuant to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) that pertain to the operation of the Columbia River Basin dams. Each time, a judge has found that the measures prescribed in the biological opinion will not save the salmon. The fifth judicial opinion was quite a tongue lashing and told the federal government to consider dam removal. A sixth biological opinion is in preparation.

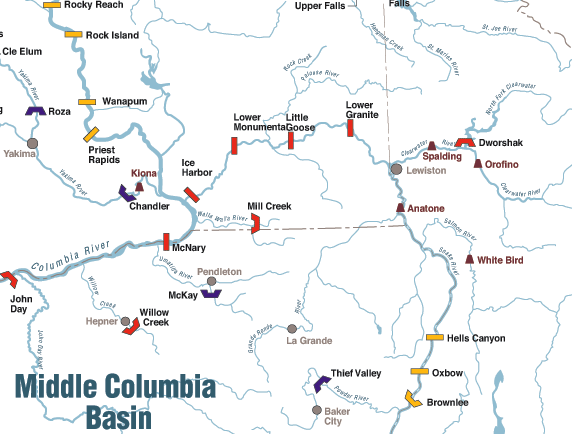

The federal agencies (mainly but not exclusively the Bonneville Power Administration or BPA) have billions and billions of dollars at the margin to save the salmon, but not on the only thing that will really save the salmon: removal of four dams on the lower Snake River in Washington State (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The four lower Snake River dams that need to come out now: Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose, and Lower Granite. (Red = Army Corps of Engineers, purple = Bureau of Reclamation, yellow = other. A rectangle image indicates a run-of-the-river dam, while the other dam(n) symbol means fluctuating level to accommodate flood control and/or irrigation downstream.) Source: Wikipedia.

All anadromous (born in fresh water, living in the ocean, and coming back to the same place to spawn) salmonid (salmon and steelhead) stocks in the Snake River are protected under the Endangered Species Act. Alas, while the Endangered Species Act requires preferred—not equitable—treatment for listed species, it cannot be used to force dam removal. Such will take an act of Congress.

The Death Spiral of the BPA

A lot of circumstances have changed since the NW Power Act was enacted in 1980. For example, the aluminum companies are gone, having gotten even better electricity subsidies in other parts of the world. And the BPA, the federal power marketing agency for thirty-one federal dams, no longer has the cheapest electricity.

The good news (at least for imperiled Snake River salmon) is that the BPA is in a death spiral. E&E News recently published a detailed story entitled “Hydropower giant Bonneville Power is going broke,” part of their series called “Bloodbath: Red Ink Pours over Northwest Dams.” In essence, the BPA’s business model is collapsing.

The BPA used to supply most of the region’s electricity and at cheap rates—cheap because the cost of power didn’t reflect the costs to fish and wildlife, and surplus power not needed by Pacific Northwest interests could be sold to the California market for a very profitable premium. California has moved on to solar and wind power, which is increasingly the lowest-cost source of new electricity production.

The BPA’s long-term contract with public utilities in the Northwest expires in 2028. Under those contracts, the utilities are paying BPA $36 per megawatt-hour. If they could, they would buy power on the open market at $22. The utilities are not rushing to renew their BPA contracts and likely won’t.

The BPA is losing money and not adequately maintaining and upgrading its infrastructure. As it loses customers, it must raise prices to cover its costs, making it lose more customers. It is likely that the BPA’s cap for borrowing from the federal treasury will be met by 2023. “If this were a private company, you would be shorting BPA,” said Tony Jones, an economist at consulting firm Rocky Mountain Econometrics. “If it was a private-sector company, it would restructure. Or this would be a good time to declare bankruptcy.”

The Last Best Chance for Snake River Salmon

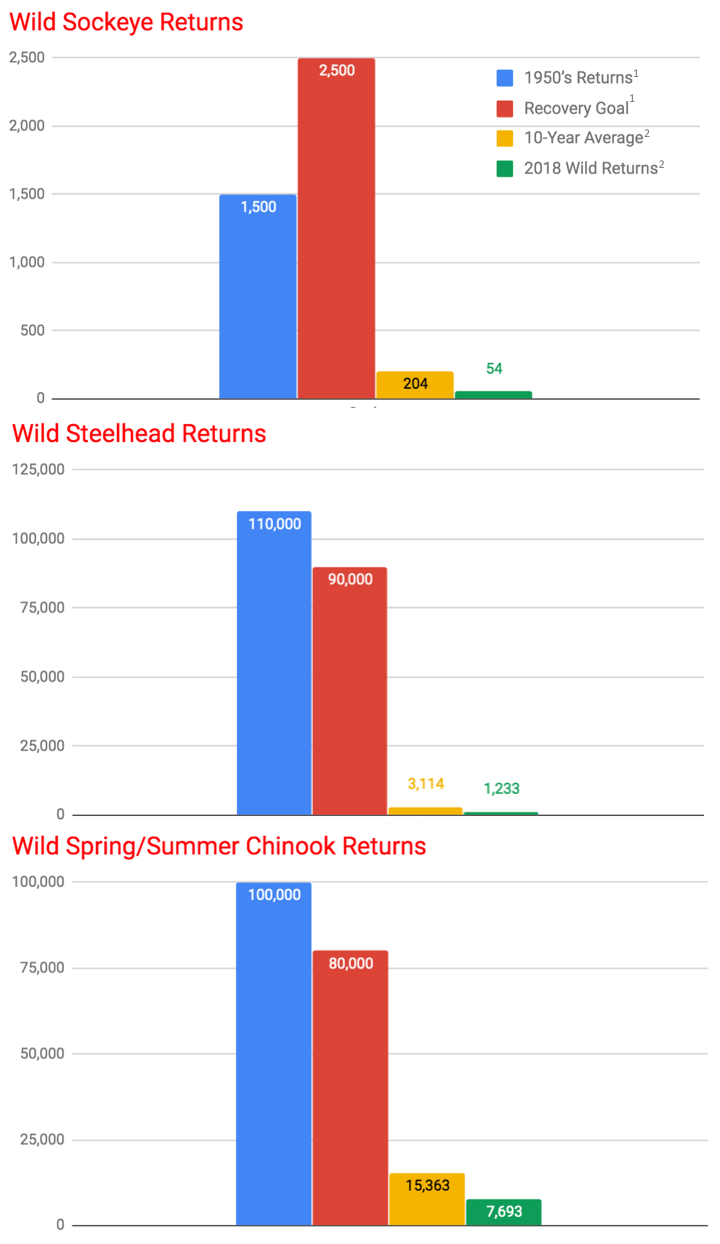

By any estimate, Snake River salmon stocks are nearing extinction (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Today’s wild sockeye, steelhead, and chinook returns to the Snake River are dwarfed by 1950s returns and estimated historic levels. Source: Save Our Wild Salmon.

According to Save Our Wild Salmon:

Snake River sockeye salmon—the region’s most endangered fish—spawn in the high-elevation lakes of central Idaho. Returns in 2018 were only about 25 percent of the ten-year average and 3 percent of what was seen in the 1950s. Historic runs (not represented in Figure 5) to Idaho’s high mountain lakes used to be 100,000+ fish a year.

Snake River wild steelhead returns in 2018 were 40 percent of the ten-year average. Not good, but better than sockeye, right? Unfortunately not, as this number is just 1 percent of levels in the 1950s. Historic runs (not represented in Figure 5) of steelhead to the Snake River Basin are estimated to have been approximately one million fish annually.

Spring/summer chinook were historically Idaho’s most prolific salmon. Now the river experiences 50 percent returns compared to the most recent ten-year average, but only 7 percent of 1950s/pre-dam-construction numbers. Historic returns (not represented in Figure 5) of Snake River spring/summer chinook are estimated to have been approximately two million fish annually.

Save Our Wild Salmon (SOS) has compiled a compelling biological and economic case for removal of the four lower Snake River dams. The Fish Passage Center, a creature of the NW Power Act funded by various entities, estimates that removing the four lower Snake River dams would increase fish survival fourfold. NOAA Fisheries says mere dam removal is not enough, and they are right.

Wild salmon runs in the Columbia Basin have been affected by the four H’s:

• hydropower impairment (dams, most that produce power, but also some that don’t)

• harvest diminishment (fought over by Native American, sport, and commercial fishing interests)

• habitat destruction of spawning, rearing area

• hatchery pollution (displacing the wild gene pool with inferior but voluminous numbers of hatchery frankenfish)

Hatcheries were invented to mitigate the massive loss of habitat (due to mining, roading, logging, grazing, agriculture, cities, and such), massive harvest pressure, and massive concrete barriers barring or impeding the comings and goings of salmon. Hatcheries need to be phased out and habitat restoration phased back in, and harvest needs to be adequately restricted to give stock a chance to recover. But addressing only three H’s and not all four H’s results in a fifth H—in the words of legendary salmon scientist and activist Ed Chaney, horseshit.

In the science and politics of salmon it may be horseshit, but in the science of politics the functional equivalent is bullshit.

An Eisenhoweresque Grand Bargain: Northwest Power Act 2.0

That aforementioned member of Congress from Idaho is pledging an all-out effort to cut through the political bullshit and save his beloved “Idaho salmon” (Figure 6). (Given the hydrogeography, removing the four lower Snake River dams to save those salmon in Idaho will also save salmon in the Grande Ronde and Imnaha Basins of northeast Oregon.)

Figure 6. A salmon stream in central Idaho. Source: Save Our Wild Salmon.

The member of Congress who is suggesting that a grand bargain can be made that will return wild salmon to Idaho (and parts west) by removing four Army dams is Republican Mike Simpson. Simpson, sixty-eight, is in his eleventh term in the House of Representatives and is ranking member (the most senior member of the minority party) of the Subcommittee on Energy and Water Development of the House Appropriations Committee. He is also on the Interior and Environment Committee.

In June 2019, Simpson gave a remarkable speech at the Andrus Center for Public Policy at Boise State University, in which he said:

The [political] reality is [that] you cannot write a new BPA act, you cannot write a new Northwest Power Planning Act without addressing the salmon issue. You can’t address the salmon issue without addressing dams. And you cannot address the salmon issues without addressing the challenges that the BPA has—they are interwoven. So perhaps this challenging time gives us the opportunity to both address the power challenges that we face and the salmon crisis.

While I disagree with Mike Simpson on most issues (see below), in this case he’s on the right track to come up with an Eisenhoweresque political solution to a problem that so far has been unsolvable. He’s calling it the Northwest Power Act 2.0. Simpson’s speech is part of the beginnings of a conversation he is insisting that the various powers centered on the Columbia and Snake Rivers have. He hasn’t offered legislation yet. He knows it will be an incredibly heavy lift. If he succeeds, it will be an enduring legacy to the benefit of this and future generations of both sapien Idahoans and salmonid Idahoans.

Mike Simpson?!

Mike Simpson (Figure 7) has earned an A+ rating from the National Rifle Association, a 100 percent lifetime rating from National Right to Life, and annual recognition from the American Conservative Union. He proudly voted to repeal Obamacare more than fifty times. He loves to cut the budget of the Environmental Protection Agency. He wants to “reform” the Endangered Species Act (well, so do I, but in the opposite way). He wants to break up the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, hoping that a new circuit including Idaho will be more conservative. He helped delist the gray wolf from the Endangered Species Act. He loves nuclear power. His lifetime rating with the League of Conservation Voters is 8 percent.

Figure 7. Representative Mike Simpson (R-ID). Source: Simpson for Congress.

However, Simpson successfully shepherded legislation through Congress that established additional wilderness areas in Idaho (not as much as I’d like, but I’m rather politically insatiable when it comes to wilderness). Most important, that legislation was accompanied by a provision facilitating the voluntary relinquishment by willing sellers of federal grazing permits in and near the new wilderness areas.

At the Andrus Center, Simpson spoke from his heart on the importance of wild salmon:

I went last year with some of my staff up to Marsh Creek up by Stanley to watch a salmon come back, create its redd, lay its eggs, and die. It was the end of a cycle and the beginning of a new one. These are the most incredible creatures I think that God’s created. It’s a cycle that God created. We shouldn’t mess with it.

When you think of what these salmon go through when they came back—and I say salmon, not salmons. We saw one. One. She swam nine hundred miles after swimming around in the ocean for five years, after being flushed through dams and out into the ocean. She swam nine hundred miles to get back to Marsh Creek‚ increased in elevation about one and a quarter miles, all to lay her eggs for the next generation of salmon.

And you gotta ask yourself after spending sixteen billion dollars on salmon recovery over the last however many years, Is it working? All of Idaho’s salmon are either threatened or endangered. Look at the number of returning salmon, and the trend line is not going up—it’s going down. And yeah, we have blips. Few years pass and you see numbers kinda come back up, then they go down again—but the overall trend is down.

The salmon recovery efforts that we have been engaged in so far have probably kept the salmon off the extinction list. But we should not manage just to keep these salmon off the extinction list. We should manage them to bring back healthy sustainable salmon populations in Idaho.

If only Nixon could go to China, perhaps only Simpson can save the salmon.

Special Interests That Must Be Made Whole

The bad news is that hundreds of millions of dollars are being spent annually by the federal government in mostly bad ways to prevent extinction of the salmon runs. The good news is that the same hundreds of millions of dollars could be spent annually in mostly good ways to restore the salmon runs to healthy, harvestable, and sustainable levels. Rather than spending the money propping up unsustainable economic activities, the government could spend the money compensating the vested economic interests to go peaceably into a mid-twenty-first-century southeast Washington–northern Idaho economy that isn’t based on salmon-killing activities.

The “port” of Lewiston, Idaho. Portland, at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers, is 111 miles upstream from the Pacific Ocean, and constant dredging is required to keep the port open. The natural deepwater ports of Seattle, Long Beach, and San Francisco don’t have a treacherous bar between them and the ocean. As a result of these factors and bigger vessels, container shipping is much diminished in Portland. Many of the good people of Lewiston in the northern portion of the landlocked state of Idaho seem to believe that there is an Eleventh Commandment (and/or a Twenty-Eighth Amendment) that specifies that Idaho should have a seaport. While Idaho does have a seaport, it comes at great expense to the federal taxpayers and the salmon stocks of the Snake River. Lewiston is 465 miles from—and 736 feet above—the Pacific Ocean, requiring ships to go through eight locks. The Port of Lewiston should be compensated for the loss of its assets that will be stranded by the end of Idaho’s only seaport. And Lewiston should be helped in retooling itself for the rest of the twenty-first century.

Barge companies. No locks (Figure 8), no reservoirs, no barges. The Snake River barge business will be kaput and the interests should be compensated for their assets stranded by a change in federal policy.

Figure 8. A barge and a tugboat in a navigation lock. Source: Save Our Wild Salmon.

Irrigators. Some farmers pump irrigation water out of some of the reservoirs on the lower Snake River. When the reservoirs are gone, they will have to lower their pumps to get their water out of the restored river. The higher one has to pump, the higher the cost. The irrigators should be compensated for their losses due to a change in federal policy.

The Great Northwest Railroad. When the barging option is removed, the sole shipper will be a spur line that connects Lewiston with the Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Union Pacific lines at Ayer Junction, Washington. In theory, the GNRR will make out like bandits—monopolies usually do.

Farmers. Farmers are understandably worried that they will be held hostage by the lack of competition to ship their products to market. In acknowledgment of a change in federal policy, the federal government should acquire the spur line and sell it on favorable terms to a consortium of shippers of agricultural products who will be their own customers.

Conservationists Need to Pivot

The multiple legal battles over the decades have been vital to helping salmon avoid extinction (yay! Earthjustice) and must continue. However, the conservation community should seize this Simpsonian opportunity for a grand bargain. Although such a bargain will mean swallowing some things we don’t like, it is the last best chance for lower Snake River salmon and could also be an opportunity to address other Pacific Northwest imperiled salmon stocks.

Sometimes one has to rise above principle to achieve the goal.

Figure 9. “I would love—I don’t think I can stay alive this long though—to see why they called Redfish Lake, Redfish Lake. I don’t know if we can do that during my lifetime. But we need to do it for our future generations.”—Rep. Mike Simpson. Redfish are returning Snake River sockeye salmon that spawn only in high mountain lakes. Source: Save Our Wild Salmon.

For More Information and How to Help

The best book on the subject is Recovering a Lost River: Removing Dams, Rewilding Salmon, Revitalizing Communities by Steven Hawley (Beacon Press, 2011).

For more than two decades, Save Our Wild Salmon has striven to take out the four Army Corps of Engineers locks and dams damning the Snake River. SOS is “a coalition of Northwest and national conservation organizations, commercial and sportsfishing associations, businesses, river groups and clean energy advocates working together to protect and restore self-sustaining, abundant, and harvestable populations of salmon and steelhead to the rivers, streams and marine waters of the Pacific Salmon states for the benefit of people and ecosystems.” Besides their Snake River restoration efforts, SOS also works on the climate emergency from the perspective of wild salmon, on conserving the Pacific Northwest southern resident orcas by working to give the killer whales enough wild salmon to again live on, and on modernizing the US-Canada Columbia River Treaty to make the Columbia more riverlike by requiring that a new coequal purpose of river health be added to the treaty’s current purposes of flood control and power production.

Send Save Our Wild Salmon some money and become a supporter and activist.