Top Line: Glaciers are history, in Oregon and everywhere.

Figure 1. The late Lathrop Glacier on the north side of Mount Thielsen. Source: W. E. Scott (Wikipedia).

In 1850, in what is now Glacier National Park in Montana (est. 1910) there were ~150 glaciers. In 2019, there were 25. Scientists project in 2030 there will be zero. Congressional legislation is in order to rename the protected area Glacierless National Park. The same goes for Glacierless Bay National Park and Preserve in Alaska, not to mention the 1,220 geographic features in the United States that include “glacier” in their names.

Due to climate change, the American West is dramatically warming. Glaciers are dying and snowpacks are declining as well. Ironically, this rapid melting is artificially keeping stream flows up in basins served by glaciers. When the glaciers no long melt because there is nothing else to melt, stream flows will precipitously decline.

Researching this Public Lands Blog post was akin to mourning the death of loved ones now gone and fearing the death of loved ones now here. Oregon’s glaciers, like the rest of the glaciers in the American West, and indeed the world, are doomed. At current rates of global warming, it is not a matter of whether but rather of when all the glaciers will be gone.

Fair Warning: The Oregon Glaciers Institute

We need more Oregonians like Anders Eskil Carlson. Carlson is a glacier evangelist warning us of what we have lost, are losing, and will lose. He is the president and founder of the Oregon Glaciers Institute (OGI) as well as an accomplished academic with masters and doctorate degrees in glacial geology. He has authored or coauthored (so far) seventy-seven scientific papers and recently formed Carlson Climate Consulting to advise industry (including insurance companies, enterprises based on summer and/or winter recreation, and those concerned with agriculture, fisheries, and forestry) and government on what climate disruption is and what it will do to them.

Carlson founded OGI in 2020 to “document and study the causes of glacier change in Oregon” and “produce projections of each glacier’s future to aid in environmental and economic planning for the citizens of Oregon.” Among other things, OGI is keeping a systematic deathwatch over Oregon’s glaciers.

According to OGI, “Depending on the model used, Western North America could lose 60 to 90% of its glaciers by 2100” (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. The end of glaciers in western North America: not whether but when. All scientific models project their demise but differ as to the date of extinction. Source: Oregon Glaciers Institute.

Figure 3. Glacier country in the American West. Source: Glaciers of the American West.

Just What Is (or Was) a Glacier?

Rather than attempt to explain the basic physics and hydrology of a glacier, I shamelessly quote verbatim from a very informative page on the Oregon Glaciers Institute website.

A glacier is an ice body that deforms under its own weight. To do this, the ice must be at least 30 m (100 feet) thick so that its weight causes the bottom ice to deform like toothpaste.

A glacier forms when snow lasts through the summer for many summers. Over time, that snow compacts into ice and the ice turns into a glacier once it is over 30 m thick. At that point, the ice then flows downslope to a lower and warmer elevation where it melts.

A glacier is divided into two zones: the accumulation and ablation zones. The accumulation zone is where snow survives through the summer, which will eventually turn into ice and feed the glacier. The accumulation zone is where the glacier gains mass.

The ablation zone is the region where all prior winter snow is melted and the underlying glacial ice is also melted (and sublimated directly into the atmosphere). If there is a lake in front of the glacier, then it can calve off icebergs as well. The ablation zone is where the glacier loses mass.

The dividing line between the accumulation and ablation zones is called the equilibrium line. The equilibrium line altitude (ELA) roughly corresponds with the summer snow line as well as the elevation where the mean annual temperature is 0 degrees Celsius (32 degrees Fahrenheit).

When a glacier gains more mass in its accumulation zone than loses in its ablation zone, its mass balance is positive. After several years of positive mass balance, the glacier will grow and advance downslope, increasing in size and length. If a glacier loses more mass than it accumulates, then it will retreat.

Figure 4. The accumulation and ablation zones on a glacier, separated by the equilibrium line (shown here as a dashed line). Source: Oregon Glaciers Institute.

Table 1 is my grossly simple attempt to explain what distinguishes a glacier from a mere stagnant ice body or snowfield. A glacier is a living body, while a stagnant ice body is but a corpse that will soon be consumed by elements.

The Decline of Glaciers in Oregon

Forty-three Oregon place-names include “glacier.” Most are named glaciers, but “glacier” is included in the name of a lake (in Union County), a pass (Wallowa County), a ditch (Hood River County), two mountains (Baker and Wallowa Counties), a creek (Lane County), and a headwall (Clackamas County).

If we go back 20,000 years to the last serious ice age, in addition to the Cascade Range and the Wallowa Mountains, glaciers also grew in what we now call the Strawberry Mountains, the Blue Mountains, and Steens Mountain in what we now call Oregon. But for about as long as there has been a State of Oregon (since 1859), Oregon glaciers have been in retreat. Many Oregon glaciers are already extinct.

OGI has determined that at the end of the Little Ice Age (~1300 to ~1850), Oregon had fifty-one glaciers. (What helped end the Little Ice Age was a massive increase in fossil fuel consumption, which contributes atmosphere-warming carbon dioxide.) Today, twenty-seven glaciers remain on eleven mountains (actually, it recently went down to ten).

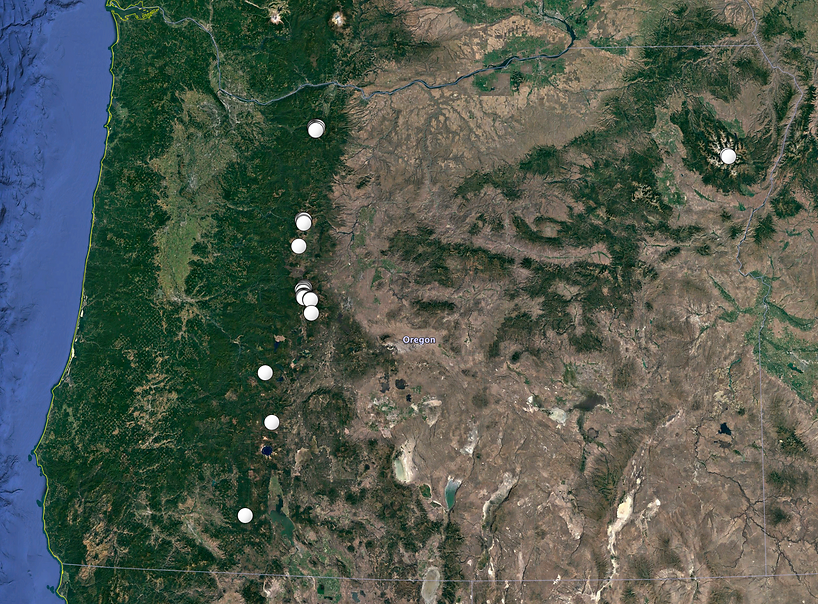

Can you name the Oregon mountains with still extant glaciers? (See Figure 5 for clues.)

Figure 5. Mountains in Oregon that still have glaciers. Source: Oregon Glaciers Institute.

In 1993, I spent six weeks hiking the Oregon section of the Pacific Crest National Scenic Trail and took note of many glaciers along the way. One was Lathrop Glacier (Figure 1) on the north side of Mount Thielsen. It was small even then, consisting of two bodies of ice at 8,500 feet elevation that were “discovered” in 1966 as the then southernmost glacier in Oregon.

I was vaguely aware that glaciers were generally in decline, but I didn’t know why. I did know that Lathrop Glacier was a small glacier. Thanks to OGI, I now know that Lathrop still had crevasses in 2013, which are indicative of glaciers, but as of 2020 Lathrop Glacier was no more.

In the late 1890s, Sholes Glacier on Mount McLoughlin held the title of Oregon’s southernmost glacier. With the demise of Lathrop Glacier on Mount Thielsen, the southernmost glacier in Oregon is now Crook Glacier on the south side of Broken Top, 66 miles north of Mount Thielsen. Alas, as OGI notes:

Crook Glacier is a very small glacier on the south side of Broken Top. It resides in a very deep cirque and receives large amounts of accumulation from avalanches. It is this shaded setting with additional avalanched snow that allows the glacier to persist as the southernmost glacier in Oregon. That said, it lacked an accumulation zone in 2021. If such phenomena persist into the future, then Crook Glacier will thin and stagnate.

It likely won’t be long before the southernmost glacier in Oregon is on the north side of Mount Hood (Figure 6).

Another Hydrological Havoc

Coincidental with the loss of glaciers is another hydrological havoc: the loss of beavers. Beavers used to inhabit almost every water body in North America, but between trapping and watershed destruction by activities such urbanization, agriculture, logging and grazing, the great riparian sponge offered by streams and lakes has been greatly diminished.

Anders Carlson writes:

Nowadays, with low snowfall winters and summer heatwaves, the snowpack either begins the summer already depleted, rapidly vanishes during the summer, or both, as was the case in the summer of 2021. Glaciers therefore play an outsized role in keeping streams flowing that would otherwise run dry. And those streams that had only snowfields in their catchment? They cease to flow.

The return of beavers at scale to watersheds can somewhat mitigate the loss of stream flow from the loss of glaciers and snowpacks (see the Public Lands Blog posts “Leave It to Beavers: Good for the Climate, Ecosystems, Watersheds, Ratepayers, and Taxpayers (Part 1)” and “Leave It to Beavers: Good for the Climate, Ecosystems, Watersheds, Ratepayers, and Taxpayers (Part 2)”).

Giving Glaciers a Chance

Only if we rapidly decarbonize our economy—in most particular, by first ending fossil fuel leasing and production on federal public lands (see the Public Lands Blog post “Keep It in the Ground”)—do any glaciers have a chance. We also need to remove excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. A great start would be to allow mature and old-growth forests and trees to grow even older and store even more carbon (see the Public Lands Blog posts “Biden’s Executive Order on Forests, Part 1: A Great Opportunity” and “Biden’s Executive Order on Forests, Part 2: Seize the Day!).

OGI should annually publish a list of current formally and informally named glaciers with a projected date of glacial death (conversion to a stagnant ice body on its way to a no-ice body), not unlike the Doomsday Clock published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Knowing the projected extinction date of Oregon glaciers can help society adapt to their loss.

One must never forget to never forget. I recommend you make a donation to OGI (I am). Besides money, OGI is interested in receiving photographs of Oregon glaciers pre-2010 to aid in documenting glacier loss. If you have any, please send them along.

For More Information

• Carlson, Anders E. 2021. “What Is a Glacier?” Mazama Bulletin 103:6.

• Glaciers of the American West (website) and Glaciers of Oregon (web page)

• O’Connor, Jim E. 2013. “Our Vanishing Glaciers: One Hundred Years of Glacier Retreat in Three Sisters Area, Oregon Cascade Range.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 114:4.

• Oregon Glaciers Institute (website)

Figure 6. Mirror Lake and Mount Hood. In a few decades Mount Hood will no longer be snow-capped in summer. Source: Wikipedia.

Bottom Line: Glacial extinction can be somewhat mitigated by addressing global warming, and the loss of stream flow from the loss of glaciers can be somewhat mitigated by introducing beavers at scale.