The excesses of the executive branch will need to be checked by the judicial branch, the legislative branch, and/or the people.

Read MoreTrump 2.0 and the Nation’s Federal Forestlands

The excesses of the executive branch will need to be checked by the judicial branch, the legislative branch, and/or the people.

Read MoreLike bankruptcy, the death of the Northwest Forest Plan has proceeded slowly and might end quickly.

Read MoreThe new administration believes that unless it can be sold or collateralized, it has no value.

Read MoreTop Line: America’s national forests have lost the greatest inside champion they’ve ever had.

Figure 1. Jim Furnish, 1945–2025. Source: LinkedIn.

I’ve interacted with hundreds of Forest Service employees since I began agitating for wilderness designation of national forest roadless areas in 1975. Of all those hundreds of Forest Service employees, only two really impressed me. Both were forest supervisors on national forests in Oregon. Both were one of a kind. In the end, the Forest Service bureaucracy rejected both.

One was Bob Chadwick, whose star shone brightest while he was supervisor of the Winema National Forest in south-central Oregon in the late 1970s. Bob died in 2015.

The other was Jim Furnish, retired (not really by his choice) deputy chief of the Forest Service. Furnish died on January 11 at his home in New Mexico at age seventy-nine. I knew he was sick but didn’t know how sick. He was on my list to do a “preremembrance” for, essentially a eulogy that the eulogized can read themselves. Alas, procrastination and denial on my part prevented me from telling Jim how much he moved the conservation needle during his life and career, so this remembrance will belatedly honor his enormous contribution.

Backdrop: The Forest Service Culture

When I started my wilderness activism, almost all Forest Service employees I met wore metaphorical green underwear underneath their green uniforms. They believed in the agency’s mission at the time: converting “decadent” and “overmature” old-growth forests into thrifty and vigorous monoculture plantations. (I’m pretty confident today that green underwear is a thing of the past in that it is rare to see Forest Service line officers wearing their green outerwear at all.)

The way one advanced in the Forest Service as a line officer (a district ranger reported to a national forest supervisor who reported to a regional forester who reported to “the chief”) was to “get the cut out.” When a “smokey” (Forest Service employee) said “the chief,” their tone of voice changed perceptibly to invoke reverence. Just about every district ranger secretly saw themselves as “the chief,” and all figured they had a good chance of being a regional forester someday.

There is a change that occurs among Forest Service line officers when they realize they won’t ever become “the chief.” Most respond by caring less and riding out their years in the Forest Service until pension time. A few (alas, very few), however, find the realization freeing.

One Exceptional Forester: Bob Chadwick

One of those exceptions was Bob Chadwick. On the Winema, Chadwick acted upon four major matters: empowering women in the agency, treating the Klamath Tribes (from whom much of the Winema was purchased) better, reintroducing fire into fire-dependent ecosystems, and—most dangerously—lowering “the cut” (the planned-for annual timber volume sold). In re the latter, Chadwick sought to protect roadless areas and dramatically lower logging levels.

Alas, this very bright star was soon extinguished. For “the good of the service,” Forest Supervisor Chadwick was “promoted” to be an “executive assistant” to the regional forester in Portland, a position that did not exist before or after Chadwick’s tenure. He was basically told to count paper clips and keep quiet. Instead, Chadwick continued to promote his idea of consensus as a better way to manage public land. He soon left the Forest Service and continued on as a consultant until he died in 2015. Bob was way ahead of his time and the Forest Service crushed him.

Another Exceptional Forester: Jim Furnish

Jim Furnish was in charge of the National Forest System from 1999 to 2002. During his tenure, he was the primary author of the Roadless Area Conservation Rule, over the objections of almost every Forest Service line officer save the top line officer, who was the only one who counted, Chief Mike Dombeck. The roadless rule, covering 58 million acres of the National Forest System’s 193 million acres, prohibits road building and almost all kinds of logging there. (Alas, some loopholes exist.) Before becoming deputy chief, Furnish transformed the Siuslaw National Forest in Oregon’s Coast Range from one of the most heavily logged national forests anywhere to one of the least logged.

Born in Tyler, Texas, Furnish got his first Forest Service job as a seasonal on the Tiller Ranger District of the Umpqua National Forest. As it was 1965 and I was in the fourth grade, our paths didn’t cross until later, when he became forest supervisor of the Siuslaw National Forest, headquartered in Corvallis, from 1991 to 1999.

In between he was a forester on the Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota, a district ranger on the Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming, a staff officer on the San Juan National Forest in Colorado, and appeals coordinator in the chief’s office in Washington, DC. After supervising the Siuslaw, Furnish was appointed deputy chief over the heads and objections of all nine regional foresters, who figured the job should have gone to them.

Furnish’s Tenure on the Siuslaw as an Agency Reformer

Furnish first came to the Siuslaw as deputy supervisor in 1991 and soon was appointed supervisor. The Siuslaw, like most national forests, was in turmoil. It was the home of both reformers who could see the forest beyond the logs-to-be and some severely unreconstructed timber beasts who sang “Timber über alles” coming and going from work, during work, and in their dreams. One Siuslaw wildlife biologist told me in the late 1980s that the only good biologists in the Forest Service were assholes. (Charlie was one of them; I loved him for it.)

Soon after becoming supervisor, Furnish forced four of the biggest timber assholes out of his office; three were given early retirement and one took a demotion.

Things began to change on the Siuslaw. The reformer Furnish soon benefited from a huge tailwind in the form of a federal court injunction against essentially all federal logging within the range of the northern spotted owl. The Pacific Northwest forest wars had gone from guerilla skirmishes to epic set-piece battles.

It was a good time to be an agency reformer. As Furnish later wrote in his memoir, Toward a Natural Forest: The Forest Service in Transition:

Prior to Judge Dwyer’s ruling, the Forest Service had inexorably, incrementally sought to tame the vast and valuable forests of the Pacific Northwest. Aggressive logging of public land rested on a foundation of a growing nation’s demand for wood. And the nation trusted the Forest Service as long as its policies seemed consistent with public values. But public values can change. Distrust can grow.

Following the war in Vietnam, a new generation viewed government with increasing skepticism and cynicism. Fewer and fewer people accepted sweeping vistas dominated by clear-cuts and new roads. Instead, they valued naturalness, clean water, abundant fish and wildlife, and a deep sense of connection with the land. They were anguished at what the Forest Service was taking from the forest at the expense of future generations.

You can plant all the trees you want, but you can’t make a forest. That’s God’s business.

Figure 2. Any reforming Forest Service employee today should read Furnish’s memoir. So too should the reconstructed (no longer unreconstructed, but still) timber beasts, who should ask themselves if anyone would bother to read their memoir if they bothered to write one. Source: Oregon State University Press.

By the way, most retired line officers in the Forest Service hated Jim Furnish, as they had made their careers by being timber beasts. Furnish was a messenger they wanted to shoot before, during, and after a district court judge and a US president told the Forest Service to obey the law.

During his tenure on the Siuslaw, Furnish did many remarkable things, but we shall focus here on timber, roads, and fish.

Changing Timber Targets

When Furnish got to the Siuslaw, the new forest plan set a target of 215 million board feet (mmbf) annually, down from 320 mamba throughout the 1980s.

(A programmed timber target was one thing; the agency was in the habit of even more logging in the name of salvage, etc. I remember the actual annual losses reaching in excess of 450 mamba. I remember that particular number because it was what Congress required the Forest Service to annually sell from the Tongass National Forest in Alaska under a law passed in 1980. The Siuslaw has 623,000 acres, while the Tongass has more than 15 million acres—equal to all national forest land in Oregon.)

President Clinton’s Northwest Forest Plan dropped the timber target on the Siuslaw to 23 mmbf from 215 mmbf. A later remapping of riparian reserves (no-cut stream buffers with a minimum of 300 feet on each side) found there were significantly more highly dissected streams in the Oregon Coast Range than first thought, and this new analysis reduced the possible timber target to ~8 mmbf. Between the ESA-protected northern spotted owl and marbled murrelet and various imperiled stocks of Pacific salmon, almost all of the Siuslaw National Forest was protected as either late-successional (mature and old-growth forest) reserves or riparian reserves, respectively.

Furnish directed the logging that could be done on the Siuslaw to focus on 120,000 acres of plantations that were established after the mature and old-growth forest was clear-cut. On those plantations, only one species, Douglas-fir, had been planted, and herbicides were often used to ensure nothing competed. The result was Douglas-fir plantations of even height and even spacing, more akin to a cornfield than a forest.

Under Furnish the Siuslaw went big on variable-density thinning, which had the objective of putting the plantations on a path to once again become mature and old-growth forests. As trees in Oregon’s Coast Range grow almost all year and generally in good soils, the logs that came from such thinning were commercially valuable to those mills that had retooled away from old growth. Most had. Not as profitable as liquidating old growth, but that ship had sailed.

Closing Roads and Helping Fish

By the time the spotted owl hit the fan in 1990 and the injunction was imposed, the Siuslaw had 2,700 miles of roads—2.7 miles of road for every square mile of land. Under Furnish, two-thirds of all the roads were closed to the public, relieving the federal treasury of the road maintenance burden and relieving wildlife of all those intrusions on what they called home.

Most Siuslaw timber roads were engineered enough to get the big logs out and to the mill but not to endure during massive storm events. Their damned culverts were engineered to allow big logs to pass over them but neither large amounts of water and large woody debris during big storm events nor fish to pass through them.

Under Furnish, the Siuslaw embarked on a massive program of making the roads hydrologically invisible to the watershed, primarily by doing two things: (1) ripping out undersized culverts to allow water and debris to flow freely, and (2) water barring the roads so the water falling on the road very soon was flowing downhill off the road and not into undersized ditches that fed those undersized culverts. The Siuslaw staff compared water-barred and un-water-barred roads, and the barred roads didn’t erode into huge landslides into creeks.

The result was improved water quality, restored fish passage, and enhanced fish habitat.

After the Fall

After leaving the Forest Service, Furnish continued to agitate from without as he had done from within. In his “retirement,” he served on the boards of several organizations, including WildEarth Guardians, Wildlands CPR, Geos Institute, and Evangelical Environmental Coalition. He was also a close advisor of the Climate Forest Campaign. He helped focus media attention on mature and old-growth forests everywhere and in particular on the Forest Service mismanaging (overcutting) his beloved Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota.

Furnish summed up his tenure at the Forest Service thusly: “The spotted owl crisis, and my years on the Siuslaw National Forest, offered many circumstances and opportunities to confront troubling realities and foster profound change.”

Thank you, Jim.

Bottom Line: Jim Furnish illustrated that although it is far too rare, a person can enter the federal bureaucracy and lease as a public servant who changed it for the better.

For More Information

American Forests. February 2, 2016. Jim Furnish, retired deputy chief, USDA Forest Service (web page).

Family of Jim Furnish. 2025. Official Obituary of James “Jim” Richards Furnish.

Furnish, Jim. 2015. Toward a Natural Forest: The Forest Service in Transition. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis.

Heller, Marc. January 14, 2025. “Logging limits pioneer dies at 79.” Greenwire.

While the election of Donald Trump is a setback for the conservation of mature and old-growth forests, such can be overcome.

Read MoreKelp forests are extraordinarily important concentrations of biodiversity and are extremely threatened, along the Oregon coast and around the world.

Read MoreTop Line: Many bitter lemons can make quite fine lemonade, but only if the conservation community reinvents itself.

Figure 1. President Biden can proclaim an Owyhee Canyonlands National Monument on his way out the door—but only if US Senator Ron Wyden asks him to. Source: Mark List.

As I sat down the morning after the election to pen some thoughts about the existential threat that Americans just elected to a second term, I went back and reviewed my Public Lands Blog post from eight years ago entitled “The November 2016 Election: Processing the Five Stages, Then Moving On.” I wish I could be as optimistic this time.

While I fear for the atmosphere, the biosphere, the hydrosphere, global humanity, and American society, I will limit my thoughts here to the conservation of nature and the protection of the environment—most especially federal public lands. Such lands were not a significant issue in the elections but will be severely affected by the results. Unfortunately, the fate of public lands has become tied to the fate of Democrats, and the Democratic Party is likely out of power in both houses of Congress and the White House. While the election results were not a mandate to further industrialize or privatize federal public lands, more of such will nonetheless be the consequence.

In this post, I shall first analyze the policy and political landscape of the nation’s federal public lands. Second, I shall make two recommendations to the lame-duck Biden administration about what to do and not do before leaving office. Finally, and most important, I shall suggest that the American conservation community fundamentally reinvent itself to become politically relevant once again.

The Forthcoming Political Landscape

The political landscape for public lands conservation during the second Trump administration will be a combination clear-cut, toxic waste dump, and minefield. Public lands conservationists will no longer be able to rely on the rule of law—neither in making, carrying out, nor interpreting the law.

The Administration

Trump 2.0 will be exponentially more awful than Trump 1.0. Trump’s mistake during his first rampage was that he appointed at least some people both smarter than him and (most important) loyal to the Constitution. They thwarted many of the dumb, mean, and/or unconstitutional things Trump wanted to do. That will not be the case this time around. In addition, the Supreme Court has since then granted a president immunity from criminal prosecution for any official act and has thus removed another restraint against abuse of power.

Much of the public lands conservation community’s work has been to use administrative processes to seek more protection for public lands. The effectiveness of this approach peaked during the Clinton administration (1993–2001) for land and the Obama administration (2009–2017) for oceans. The first Trump administration (2017–2021) was a very large negative. The Biden administration (2021–2025) wasn’t any great shakes.

The Courts

This activist Supreme Court is increasingly making it up as they go along. If a majority doesn’t like a law as a matter of substance, they creatively reason it away despite any precedence or traditional jurisprudence. Cases are before the court that could spell the end of the National Environmental Policy Act as we have known it. Other cases that similarly jeopardize the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, the National Forest Management Act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, and others are likely to get the Supreme treatment.

The Congress

In re the conservation of public lands, Congress has been getting worse. Affirmative land conservation is down, while affirmative land degradation is up by even more. Almost all of the land conservation is attributable to Democrats, while the land degradation is firmly bipartisan. The main reasons for this are money in politics and gerrymandering of congressional districts.

Gerrymandering, while a bipartisan plague, is done most effectively by Republicans. The result is that most members of Congress of both parties have extremely safe seats and are easily elected in the general election. If a seat is threatened, it’s only in a partisan primary. The Democrats take the public lands conservation community for granted, and the Republicans take us to the cleaners.

Earth to Biden Administration: For the Love of Nature, Do Nothing except One Thing

The Biden administration is set to finalize several policy initiatives that pertain to public lands, wildlife, the climate, and/or the environment. Among these are initiatives regarding old growth in the national forests, greater sage-grouse, and management of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The Biden administration should not finalize any of them. Put down the policy pen and step away.

Do Nothing!

You may be thinking, Is not half a loaf better than none? Actually, no.

Across the board, the conservation policy initiatives I’ve mentioned are very weak tea, if not bitter pills. For example, the Biden administration proposals for old-growth forests and greater sage-grouse would be a net loss for their conservation. In re the former, unbelievably, the Forest Service proposal to amend its forest management plans will result in a loss in both quality and quantity of old-growth forests. In re the latter, the prospective Biden 2024 sage-grouse plan is worse than the 2015 Obama sage-grouse plan and may not be much better the 2019 Trump sage-grouse plan.

Lest you believe such stale heels are better than half a loaf, let me tell you about the Congressional Review Act (CRA). The Congressional Research Service describes the CRA as “a tool Congress can use to overturn certain federal agency actions.” The CRA disapproval process can apply to almost any federal “rule” (including federal land and/or resource management plans) that is finalized within a specified period. For this 118th Congress, any rule finalized after August 1, 2024, is subject to a “lookback” provision when the 119th Congress convenes in January. If it were President Harris, she’d veto any joint resolution of disapproval (JRD) of a Biden rule. But it’s not.

If a CRA JRD is filed, it may receive special consideration in the House of Representatives and must receive such in the Senate. The procedure calls for a clean (no amendments) up-or-down vote in the House and Senate (where it is not subject to a filibuster that requires sixty votes to overcome). If a JRD passes both houses, it is presented to the president for signature or veto.

The Congressional Research Service explains the noose and the salting of the earth that applies to a disapproved rule:

A rule that is the subject of an enacted CRA joint resolution of disapproval goes out of effect immediately if the rule has already taken effect when the resolution of disapproval is enacted and “shall be treated as though such rule had never taken effect.” If the rule has not yet gone into effect when the resolution of disapproval is enacted, it will not take effect.

In addition, a rule subject to an enacted joint resolution of disapproval “may not be reissued in substantially the same form, and a new rule that is substantially the same . . . may not be issued, unless the reissued or new rule is specifically authorized by a law enacted after the date of the joint resolution.” [emphasis added]

So not only do we not want the Biden administration issuing weak and lame environmental rules, we also sure as hell don’t want Congress disapproving such rules and forbidding any future administration from doing another rule that is “in substantially the same form.”

Except One Thing: National Monuments

Proclamations by the president of new or expanded national monuments with the authority granted by Congress pursuant to the Antiquities Act of 1906 are not rules subject to the Congressional Review Act. Biden needs to proclaim a boatload of new national monuments. And not just a few, but severalfold more than he was contemplating before the election, with some zeros added to the acreages.

While not subject to the CRA, national monument proclamations are subject to an activist Supreme Court. Chief Justice John Roberts has written that he’s fishing for a case to gut the Antiquities Act (as the Supreme Court has gutted the Voting Rights Act and others).

If failing to act is the right course for Biden’s (wimpy) environmental rules to not get CRAed, is it not the same with national monuments? No. National monuments are quite popular, and it would be unpopular even for a popularly elected president to reverse national monument designations. If Trump is going to reverse Biden’s monuments (or the Supremes are going to gut them), they need to be made to do it out loud and in public.

Earth to Conservation Organizations: Restructure for a Changed Political Landscape

Continuing to rely on the administration, the courts, or Congress as they are now constituted to elevate the conservation status of public lands is a fool’s errand. What used to work well for the conservation community no longer does and will not again until the makeup of these federal branches changes. Such change can only come with better election results.

If I were in charge, I would institute a plethora of reforms regarding election to government office and the operation of government.

See Public Lands Blog post: “Small-d Democratic Reforms to Revive Our Republican Form of Government”

Since I’m not in charge, please permit me to suggest that conservation organizations need to fundamentally reorganize themselves to become politically relevant once again.

To conserve federal public lands, it’s now all about elections. It’s no longer about commenting on draft environmental impact statements. But due to some quirks of conservation history, most conservation organizations are organized under federal tax law in ways that prevent their effective engagement in political and election advocacy.

Most conservation organizations are organized under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. This tax status allows the organization to avoid paying taxes on its income and allows the donor to take a tax deduction for contributions to the organization. The cost of these two benefits is that the organization can only seek to influence legislation in very limited ways and cannot seek to influence elections in any way. To avoid income taxes, these organizations waive part of their First Amendment rights and most of their effectiveness.

There is another tax status, 501(c)(4), that allows the organization to avoid taxation on its income but does not give the donor a tax deduction for contributions to the organization. A “c4” can use all its funds for lobbying or influencing elections. In addition, a c4 doesn’t have to disclose the names of its donors.

While some c3s have affiliated c4s, those c4s are always much smaller than the c3 and are dusted off only briefly every two to four years for elections. In the rest of the public interest advocacy universe, organizations have a c4 as their mothership and a smaller affiliated c3 for taking in foundation money and/or large contributions from donors who insist on getting a tax deduction.

You may want to ask any conservation organization you contribute to if it is a c3 or a c4—or both. Increasingly, I’m no longer contributing to c3s but rather to c4s.

See Public Lands Blog post: “The Public Lands Conservation Movement: Mis-organized for Job #1”

In Conclusion

Here are a few excerpts from what I wrote in November 2016, followed by my thoughts today.

On this day-after I am working through my five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, grieving and acceptance. The thing about these stages is they don’t have to come in a particular order and can be repeated.

Nothing has changed eight years later.

I’m going to take a long walk with my dog and ponder next steps. A bad election outcome will cause one to change strategies and tactics, but not goals.

I took that walk but with a new puppy (that looks quite a bit like the old one) and it was 8.2 miles that day as Lucy needed wearing out and I needed refreshing.

I’ve been around long enough to remember the dark days of the Reagan Administration and the dark days of the G.W. Bush Administration. The days of Trump may be darker. In previous dark times, the Democrats generally held at least one house of Congress and served as a check on the excesses of Reagan and Bush, as did the federal courts.

This time a Republican President can sign legislation passed by a Republican House of Representatives and a Republican Senate. The only check is the Senate rule that requires 60 out of their 100 votes to end debate (aka filibuster).

Trump 1.0 was hell for the conservation of public lands. Trump 2.0 will likely be as bad or worse.

I’m willing to bet that if the House also goes Republican, as is expected, the Senate filibuster will go away. As we have been taught once again, elections matter.

In two years, there’s another election. All House members and one-third of senators will be on the ballot.

Bottom Line: The conservation community needs to fundamentally reorganize itself to matter in elections.

Utah’s lawsuit against the United States is an existential threat to more than 200 million acres of federal public lands.

Read MoreThe most ecologically rational and fiscally prudent course is to eschew thinning before reintroducing fire into fire-dependent forests.

Read MoreTop Line: The Forest Service is blowing President Biden’s chance of saving mature and old-growth forest for this and future generations.

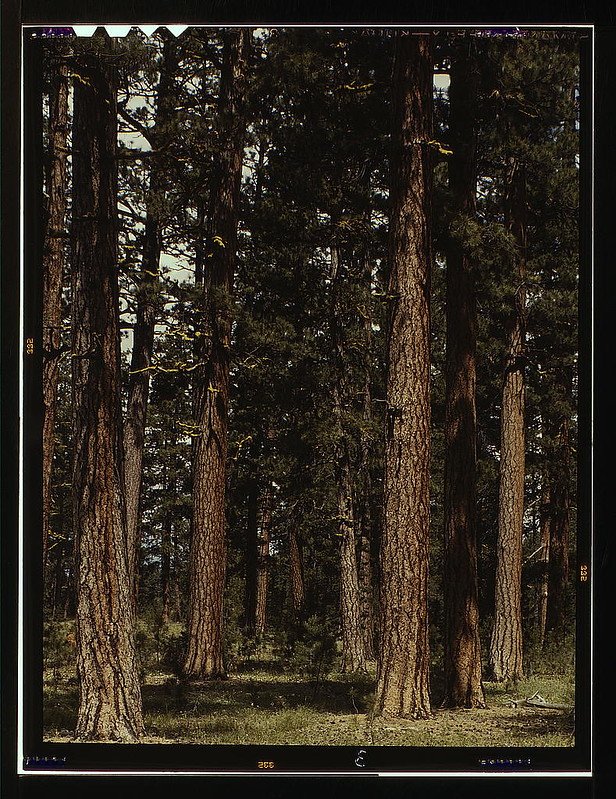

Figure 1. Cover photo, and the only photo, in the Forest Service’s National Old-Growth Amendment Draft Environmental Impact Statement. If there ever were stands of old-growth forest that don’t need any kind of “restoration” management, it’s those in the temperate rainforest of the Oregon Coast Range, in this case the Siuslaw National Forest. Source: USDA Forest Service.

In 2022, President Joe Biden issued an executive order that required the US Forest Service (USFS) to, among other things, “develop . . . conservation strategies that address threats to mature and old-growth forests on Federal lands.” The USFS has responded by issuing a draft National Old-Growth Amendment (NOGA) that would amend nearly all national forest land management plans. The NOGA has enough loopholes to drive lots of log trucks through. Public comments are urgently needed by midnight Pacific Time on September 19, 2024, to influence the Biden administration to overrule the USFS in this matter.

NOGA Background

Before issuing the NOGA, the USFS (and the Bureau of Land Management) prepared an inventory of mature and old-growth (MOG) forests. (See my Public Lands Blog post “How Much Mature and Old-Growth Forest Does the US Have Left?”) A deficiency of the MOG inventory is that while it can tell us how much mature and old-growth forest remains on federal public lands, it can only tell us where the MOG forests are at the coarsest of scales (Figure 2). (At this end of this Public Lands Blog post are regional maps of where generally the mature and old-growth forests are in the National Forest System.)

Figure 2. Where old growth is found in the National Forest System. Source: US Forest Service.

After they published their inventory, the USFS and the BLM issued an “Analysis of Threats” to MOG forests, which found that logging by the agencies is not a significant threat. Rather, MOG forests are threatened mostly by too much fire, not enough fire, insects and disease, extreme weather events, and/or climate change. Contrary to reality, the agencies don’t view themselves as a threat to mature and old-growth forests but rather as the saviors of old-growth forests. With a straight face, the USFS notes that “the lack of large log milling may hinder restoration and other vegetation management activities to improve ecological conditions in or near old-growth forests.”

In the NOGA, the USFS generally contends that judicious logging of old growth can save said old growth. Readers in my age cohort might remember those who argued during the Vietnam War that villages needed to be bombed to save said villages.

Figure 3. Old-growth forest on the Fremont-Winema National Forest in Oregon. Source: US Forest Service.

What the NOGA Would Do

Not much, really. Each national forest plan would be amended by the inclusion of nationally mandated language that sets a goal; prescribes management approaches; lists desired conditions, objectives, standards, and guidelines; outlines plan monitoring requirements; and includes a “statement of distinctive roles and contributions” for old-growth forests.

The NOGA considers a no-action alternative and three action alternatives that are identical save for the “standards” they include. Of course, the draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) is written to justify the preferred alternative, Alt 2, which includes the full suite of standards. Alt 3 would expand one of the standards to say: “Proactive stewardship in old-growth forests shall not result in commercial timber harvest.” (This is why EIS’s should be written by the Environmental Protection Agency or another federal agency that doesn’t have the biases any action agency does.)

If you wade through all the proposed verbiage (I did, but I’m not afraid of anything I can wash off or throw up), you will come away disappointed. In essence, the USFS is saying in the NOGA

• it cares about old growth,

• it will give more lip service to old growth, but

• the only way to save old growth from all those threats is to manage (the USFS likes the term steward, which means log in this case) old growth.

Better Than Nothing, or Nothing Is Better?

A happy take on the USFS NOGA is that the agency is recognizing for the first time the importance of old-growth forests, and such is, well, a start. A pessimistic (pronounced “realistic”) take is that no NOGA is better than this NOGA. Unless the USFS drastically changes its proposed action in the NOGA, the best thing for MOG on the national forests is for the final NOGA never to see the light of day.

If there is a stand of old-growth forest that has stood for a millennium, there is nothing in the USFS’s proposed new management direction that forbids the agency from logging it (of course, in the name of saving it). There is no age of old-growth forest that is too old for the Forest Service to “save.”

If the Forest Service definition of old growth for a particular forest type is a minimum of eight large trees per acre, then an acre that includes twelve such large trees can be shorn of four of those large trees and still be classified as old growth. If an acre has only seven large trees, then screw it, according to the Forest Service.

Figure 4. Cover photo, and the only photo, in the Forest Service’s “Technical Guidance for Standardized Silvicultural Prescriptions for Managing Old-Growth Forests.” If there ever were stands of old-growth forest that don’t need any kind of “restoration” management, it’s those in the temperate rainforest of the Oregon Coast Range, in this case the Siuslaw National Forest. Source: USDA Forest Service.

Why the Forest Service Is Such a Disservice

The Forest Service, an agency of the US Department of Agriculture, historically treated any forests of commercial value as a row crop: harvest, plant, harvest, plant, harvest . . . I guess it’s progress that the agency now views forests as more like an orchard, which cannot be sustained without a lot of management.

Like all bureaucracies, the USFS is made up of bureaucrats. If there is one thing all bureaucrats hate, it is to have their discretion limited. Truly saving old-growth forests and trees for this and future generations means limiting the discretion of USFS bureaucrats to manage or choose between competing uses (where many actually are abuses).

The Biden executive order addressed both “mature” and “old-growth” forests and trees equally. Conservation strategies were to address the threats to both. However, the USFS has failed to address mature forests in the NOGA, other than to note that some mature forests might later be drafted to become old growth. In essence, the agency choked on the M in MOG when it discovered how much M forest exists. Saving mature forests would mean the agency’s logging sandbox would be substantially diminished. The USFS is also banking on the public placing less value on mature as compared to old-growth forests.

As far as the NOGA goes, to the USFS old growth is never a place nor an ecosystem but merely a silvicultural state. If a fire converts an old-growth forest to a preforest (aka early seral forest, quite the ecosystem in itself), the “protections of the NOGA” no longer apply. The USFS will likely want to salvage log the old dead trees and quickly plant new ones so the site can, over silvicultural time, become “old growth” again. (See my Public Lands Blog posts: “Preforests in the American West, Part 1: Understanding Forest Succession.” and “Preforests in the American West, Part 2: “Reforestation,” By Gawd?”.)

Concurrent with the NOGA, the Forest Service is updating Forest Service Manual 2470: Silvicultural Practices. Silviculture is the “growing and cultivation of trees.” This NOGA is the product of a silvicultural circle jerk. (Lest you are aware only of the definition of this term offered second in my Apple Dictionary, permit me to offer up the first definition:

1 informal a situation in which a group of people engage in self-indulgent or self-gratifying behavior, especially by reinforcing each other’s views or attitudes: “those award ceremonies are big circle jerks.”

Figure 5. Old-growth forest on the Bitterroot National Forest in Montana. Source: US Forest Service.

The USFS view is generally that old growth cannot be left to nature but must be actively stewarded by foresters. While this is depressing, don’t be depressed. The Biden administration can save the old-growth forests from the Forest Service. Part of Joe Biden’s legacy can be actually saving the old-growth forests for this and future generations.

How You Can Help

For the conservation community to make the case for the Biden administration to act decisively and overrule the Forest Service before the new president takes office on January 20, hundreds of thousands of comments must be submitted on the NOGA. That’s where you come in. The USFS (actually the White House) needs to hear from you!

You can send an official comment to the USFS through the Climate Forests Campaign (CFC) action webpage. After you submit your comment through that portal, the CFC will bundle it with others’ comments and submit the lot through the official USFS web portal. (The CFC will also be making sure the White House knows of your and all that other public support to really protect old-growth forests.)

It is vital that you send your comment for the official record by midnight Pacific Time on September 19, 2024.

The CFC offers suggested language for your comment. Please delete the language in the comment box and then copy and paste the following language (much of which is the same, but with some important additions):

The Forest Service should adopt a record of decision that is a strengthened version of Alternative 3 in the Draft Environmental Impact Statement—modified as recommended in detailed joint comments you are receiving from a coalition of national, regional, and local conservation and public interest organizations.

Mature and old-growth trees and forests protect our climate by absorbing and storing carbon, boost resilience to fire, help regulate temperatures, filter drinking water and shelter wildlife. Logging them deprives us of the benefits and beauty of our largest, oldest trees.

The proposal allows old-growth trees to be sent to the mill and allows agency staff to manage old-growth out of existence in pursuit of “proactive stewardship” goals. The draft also contains ambiguous language that could be used to justify continued commercial logging of old growth in the Tongass.

The final record of decision should:

1. End the cutting of old-growth trees in all national forests and forest types and end the cutting of any trees in old-growth stands in moist forest types.

2. End any commercial exchange of old-growth trees. Even in the rare circumstances where an old-growth tree is cut (e.g. public safety), that tree should not be sent to the mill.

Cutting down old-growth trees to save them from potential threats is a false solution. They are worth more standing.

Mature forests and trees–future old growth–must be protected from the threat of commercial logging in order to recover old growth that has been lost to past mismanagement. They must be protected to aid in the fight against worsening climate change and biodiversity loss. And they must be protected to ensure that our children are able to experience and enjoy old growth.

Failure to protect our oldest trees and forests undermines the objectives of this amendment, contravenes the direction of EO 14072, and ignores 500,000+ public comments the agency previously received.

The vague language at the end of the first paragraph is because the referenced comments have yet to be finalized and sent. Rest assured they are going in, and they will be good. (I’m helping to draft them.)

Don’t delay. Please act now before you forget or get distracted. Here’s the link again.

Figure 6. A tiny sequoia in front of a giant sequoia on a national forest in the Sierra Nevada of California. Source: US Forest Service.

Bottom Line: Send your comment now! It won’t persuade the Forest Service, but it could help persuade the White House.

Figure 7. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Northern Region (Region 1). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 8. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Rocky Mountain Region (Region 2). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 9. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Southwestern Region (Region 3). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 10. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Intermountain Region (Region 4). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 11. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Pacific Southwest Region (Region 5). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 12. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Pacific Northwest Region (Region 6). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 13. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Southern Region (Region 8). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 14. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Eastern Region (Region 9). Source: US Forest Service.

Figure 15. Percent of old growth in forests in the USFS Alaska Region (Region 10). Source: US Forest Service.

This is the first in a series of two Public Lands Blog posts regarding the idea that commercial thinning of frequent-fire-type forests should take place before reintroducing fire. Part 1 sets the stage with a review of past thinking about thinning. Part 2 will examine the new science and its implications for policy.

Top Line: A new scientific review of many scientific papers suggests it is not necessary to thin before reintroducing fire into fire-dependent forests.

Figure 1. Prescribed burn in ponderosa pine forest near Black Butte, Oregon. Source: Oregon Wild.

I have long been on record (egad, I sound like a politician) in favor of limited logging in certain degraded forest types to aid in the conservation or restoration of old-growth forests. Until very recently, scientific papers have generally confirmed both the problem and the solution to degraded (roaded, high-grade-logged, livestock-grazed, and/or fire-excluded) frequent-fire (aka dry) forest types. Coincidentally, the thesis has also been supported by political science (aka politics). But of late, the conservation science of dry forest restoration has changed—and politics must follow.

When Belief in Thinning Held Sway

Here’s the abstract from a white paper I did in 2007:

Politics makes for strange bedfellows and that is particularly the case today with the restoration of Oregon’s public forests. Conservationists must work with cooperative elements of the timber industry to achieve ecological restoration of certain forest types exhibiting certain stand conditions. Significant amounts of this forest restoration will require some commercial logging—“thinning”—albeit only for a few decades and taking much smaller diameter trees than in the past. Logging for ecological restoration will produce much less timber than was historically removed from federal forests, but significantly more timber than has been removed in recent years. Carefully controlled thinning projects in certain forest types with certain stand conditions must be a part of a scientifically justified program of forest restoration that includes protecting all old growth trees, creating more old growth trees, preserving roadless areas, removing roads, removing livestock and/or reintroducing natural fire to forest ecosystems. [emphasis added]

My white paper was based on the best conservation science available at the time. In 2010 my belief in thinning caused me to testify, along with John Shelk of Ochoco (aka Malheur) Lumber Company, in support of legislation developed by Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) and cosponsored by Senator Jeff Merkley (D-OR). The proposed “Oregon Eastside Forests Restoration, Old Growth Protection, and Jobs Act of 2009” would have been a serious net gain for the conservation of federal forests in eastern Oregon. It would also have been a supply lifeline to the local mills throughout the east side. Unfortunately, not all of Big Timber was on board. At that time, Big Timber held less economic and political power than at its peak in 1990, but its power was still quite considerable. Today, it’s far less so.

Figure 2. Senator Ron Wyden’s bill S.2895, 111th Congress. It would have been a net gain for conservation while also aiding the timber industry, but not enough of Big Timber could see the light. Source: Congress.gov.

First there were the mills in eastern Oregon that would have benefited from a larger and more secure supply of timber, but these operators opposed the bill anyway. More problematic was the vast majority of the timber industry in Oregon that is based west of the Cascade Crest. These mills feared that a congressional grand bargain for Oregon eastside forests would harm their efforts to have everyone believe that the Oregon and California Lands Act of 1937—which applied to approximately two million acres in western Oregon administered by the Bureau of Land Management—was in fact not a combination 11th Commandment and 28th Amendment but merely a congressional statute that could be amended or repealed.

The upshot was that the grand bargain for Oregon eastside forests did not become law. Nonetheless, elements of this grand bargain were generally implemented by the Forest Service. Operating under the Eastside Screens, the agency was no longer logging old-growth trees but instead was putting up timber sales that thinned the forest with an eye to preventing the relic big trees from succumbing to insects or disease exacerbated by thickening forests caused by fire exclusion. The mills that had retooled for smaller logs were getting their timber supply and without significant controversy or delay.

Figure 3. Pile burning on the Deschutes National Forest, Oregon. Under pile burns is often scorched earth, and the small fuels across the site are left untreated. Source: USDA Forest Service.

Forest Service Reversion to Bad Habits

Yet, the longer the time since the implementation of the Eastside Screens in 1995, the more the Forest Service was drifting into cutting very large trees. The mills did not complain. In fact, in 2022 the Forest Service abandoned the Eastside Screens in favor of a far less protective regime to “conserve” old-growth forests and trees. Fortunately, the nefarious replacement was found to be illegal by a federal court judge in 2024. While the Forest Service is licking its wounds, the agency hasn’t seen the light.

Since the Forest Service has lost its social license to log old-growth forests to supply mills with logs, it has invented many a creative “reason” that old-growth trees should be turned into large logs. The Forest Service says it must log the mature and old-growth forest to save it. From fire, from insects, from disease, from windstorms, and from climate change—and actually from any kind of change including that of natural ecological succession.

To whatever question or challenge the Forest Service faces, its answer is logging. When your only tool is a chainsaw, every tree looks like a standing log.

The Forest Service continues to log in the name of “forest health,” “resiliency,” “fuels reduction,” or any other “reason” to such a degree that it is now shipping logs from California, where none of the local mills want them, to a mill in Wyoming near the Black Hills National Forest. The Forest Service has so overcut/raped the Black Hills National Forest that the local mills have no choice but to accept the essentially free logs (your tax dollars at work) from national forests in California.

Shifts in the Policy Equation and Conservation Science

The political/policy equation has shifted. The Forest Service is full-on crazing again to log old-growth forests and trees—albeit in the name of “saving” them. Big Timber can no longer be relied upon to live on smaller ecologically surplus logs. As the timber industry has shrunk in eastern Oregon, the bureaucratic business model of selling or giving away logs to Big Timber in exchange for taking smaller logs and also doing restoration work such as culvert and/or road improvement or removal is no longer working as it did.

Most important, the conservation science on reducing wildfire severity has shifted. The general concern is that many frequent-fire-type forests are overgrown or far more densely stocked than was the case before natural fire cycles were interrupted. This overgrowth is due to

• high-grade logging (logging out the most fire-resistant old-growth trees in the stand),

• fire exclusion (disrupting the relatively frequent but low-severity fire cycle by suppressing fires), and

• livestock grazing (eliminating fine fuels—aka “grass”—that carry beneficial fire).

Frequent-fire-type forests burn, as the name suggests, frequently, but characteristically at low to mixed intensities. While stand-replacing fires can occur in frequent-fire-type forests, they are far from the norm. The thinking was (for me) and still is (for many) that such forests need to be thinned first, with “fuel loads” being reduced by logging and removal of wood to the mill, before fire can safely be reintroduced.

The problem is that ecologically disrupted frequent-fire forests are far more subject to “uncharacteristic” fire—that is, stand-replacing fire. While stand-replacing fire did occur naturally, it was not characteristic of the forest type.

Figure 4. Prescribed burns often kill younger, smaller trees, but not often larger, older trees. Source: USDA Forest Service.

Next week in Part 2, I will suggest that the Forest Service eschew thinning and embrace fire.

The reduction of surplus production capacity continues to result in lumber mill shutdowns, though the contributing factors cited have changed as times have changed.

Read MoreTop Line: Senator Wyden is cosponsoring legislation that would give blank checks and get-out-of-jail-free cards to all BLM grazing permittees and lessees.

Figure 1. A bovine on public lands crapping in the same stream from which it drinks. In the absence of domestic livestock, this stream would be colder and deeper, well shaded by willows if not also cottonwoods, and likely full of trout. Source: George Wuerthner.

Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) is the sole cosponsor of a bill by Senator John Barrasso (R-WY) that would give Bureau of Land Management (BLM) grazing permittees and lessees even more free rein than they have now to (ab)use the public lands. The Barrasso-Wyden bill, the Operational Flexibility Grazing Management Program Act (S.4454, 118th Congress), would effectively remove any administrative control the BLM has over the grazing of livestock on 155 million acres of federal public lands.

As a senator from Wyoming, Barrasso has long carried any and all water requested of him by public lands grazing permittees and lessees. The Barrasso-Wyden bill is the latest in a long line.

Wyden’s Proposed Owyhee Canyonlands Bill: Quid Pro Quo

This is not Wyden’s first legislative attempt on behalf of grazing “flexibility.”

For the past several years, Senator Wyden and his staff have labored long and hard to bring forth legislation to address public land management issues in Malheur County, Oregon. The latest incarnation of his Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act, would primarily do two things on BLM holdings in Malheur County:

• Establish ~1.1 million acres of new wilderness areas.

• Authorize “flexible” livestock grazing on BLM lands in Malheur County.

The bill would do other things, but most of the verbiage pertains to wilderness and livestock grazing.

Wyden’s bill proposing a wilderness–livestock grazing grand bargain in the Owyhee Canyonlands (S.1890; 118th Congress), was introduced in the Senate in June 2023, reported out of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee in December 2023. A vote of the full Senate has not been scheduled. Most, but not all, of the conservation community supports S.1890 and they feel it is—despite a grazing “flexibility” provision—a significant net gain for public lands conservation.

Figure 2. Land near Kemmerer, Wyoming. On one side of the fence, the land is ungrazed. Guess which side. Source: George Wuerthner.

Here are two political givens:

• Conservationists love wilderness and hate livestock grazing.

• Public lands ranchers love livestock grazing and hate wilderness.

However, there is a place where these two sets overlap (picture a Venn diagram), and Wyden has found it in his Owyhee bill. Public lands ranchers really want “flexibility” language and are willing to give 1.1 million acres of wilderness to get it. Conservationists really want 1.1 million acres of wilderness and are willing to give a carefully worded and constrained version of grazing “flexibility.”

In the crafting and politics of legislation, such is known as a quid pro quo. One faction gets something they want more by accepting something they want less. Happens all the time.

The proposed wilderness boundaries and grazing language were long debated and fought over, but Wyden’s latest bill seems to thread a political needle.

In cosponsoring S.4454, Wyden has tossed aside the delicate compromise offered in his Owyhee legislation and embraced a unilateral and far more damaging giveaway to the public lands livestock industry.

Figure 3. Livestock in the Sonoran Desert National Monument in Arizona. Source: George Wuerthner.

The Entrails of the Barrasso-Wyden Bill: Quid Pro Nihilo

“Flexible” grazing is not bovines practicing their yoga cow pose.

It would be bad enough if Wyden had taken his Owyhee “flexibility” language national and offered it without any corresponding conservation (a.k.a. “wilderness”) offset. However, the Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language is arguably ten times worse in effect than the Wyden (Owyhee) “flexibility” language.

The Wyden (Owyhee) version of “flexible” grazing contains sideboards and leaves public lands managers with their ability to manage grazing on public lands. The Barrasso-Wyden (national) version of “flexible” grazing means that public lands ranchers get to do even more of what they want on public lands, with the public lands managers no longer having a say, with no analysis and stewardship requirements.

The Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language is a total giveaway of blank checks and get-out-of-jail-free cards to grazing permittees and lessees on public lands administered by the BLM.

Figure 4. Livestock near the Paria River in the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument in Utah. I honestly don’t know what they are eating. Source: George Wuerthner.

The public policy director for the Western Watersheds Project (WWP), Josh Osher (my go-to guy for all matters of public lands grazing policy), submitted testimony (on behalf also of Kettle Range Conservation, Oregon Natural Desert Association, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, and Wilderness Watch) in opposition to the Barrasso-Wyden bill (WWP et al.). The bottom line:

S. 4454 is an attempted end around to virtually eliminate NEPA requirements and public involvement in grazing management on public lands. This bill puts all of the power in the permittee’s hands and removes nearly all discretion from the Secretary to manage grazed lands for multiple use. Passage of S. 4454 would lead to continued failure of BLM managed lands to meet even the most basic standards for land health and eliminate the few remaining tools at the BLM’s discretion to address problematic livestock grazing. [emphasis added]

How does the Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language compare to the Wyden (Owyhee) “flexibility” language? The WWP letter notes:

Furthermore, this legislation is a significant departure from the current pilot program initiated by the BLM and the operational flexibility language in S. 1890, the Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act. S. 4454 dramatically expands the purposes for modifying the terms and conditions of grazing permit from responses to environmental factors and ecological conditions to now include producer preferences and responsiveness to market conditions. [emphasis added]

The Barrasso-Wyden “flexibility” language would make a complete sham of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) by requiring the BLM to always choose the “flexible” grazing alternative. The WWP letter notes:

The bill language states that the “Secretary shall develop and authorize at least 1 alternative” for operational flexibility. It is unclear if “authorize” means that alternative must be chosen or simply analyzed with the discretion remaining with the Secretary to determine which alternative to implement. If the former, this a complete usurpation of the Secretary’s authority to manage public lands according to multiple use principles. [emphasis in original]

The WWP letter further notes:

The final section that prohibits termination of a grazing permit due to the use of operational flexibility functions to fully insulate the permittee from any consequences of bad management choices for which the Secretary had no discretion to modify or deny. [emphasis added]

In reading legislation, I always try to follow two principles:

• Read the language as if you are paranoid. Read the language in a way that the forces of darkness could/would interpret it if they were in charge. Just because one is paranoid, it doesn’t mean that one is not being followed.

• Clearly discern what is being done for you and what is being done to you in the legislative language. The Barrasso-Wyden bill is all the latter and none of the former.

Rather than an acceptable quid pro quo, the Barrasso-Wyden “flexibility” language is a quid pro nihilo (something for nothing). Something for public lands ranchers, nothing for conservationists.

Figure 5. Livestock in the Eagletail Mountains in Arizona. Source: George Wuerthner.

A Benign Bovine: No Such Animal

Let’s take a moment to remind ourselves why livestock production—especially on public lands—is problematic.

Domestic livestock have done, and are doing, more damage to Earth than the chainsaw and bulldozer combined.

Livestock production—primarily cows—accounts for 14.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions (a few sources say less, most sources say more), most in the form of methane emitted by belching bovines. A molecule of methane has a global warming potential at least 28 times greater than that of a molecule of carbon dioxide. Animal agriculture also produces 65 percent of the world’s emissions of nitrous oxide (yes, laughing gas, but no laughing matter here), which has a global warming potential 296 times greater than that of carbon dioxide. In addition, 70 percent of the world’s agricultural lands are dedicated to livestock—lands that were formerly forests, grasslands, and/or wetlands.

Locally—and most especially on public lands—livestock cause chronic and grievous environmental harm. Most streams flowing through public lands have been cow-bombed to such an extent that water quality is horrendous and water quantity is diminished.

Figure 6. Fresh cow shit on rocks in a stream on public lands. If it were deposited on land, many would call it a cow pie. I do not. Unlike pie, cow shit is neither sweet nor savory. Source: George Wuerthner.

The public land forage now consumed by one cow and one calf could be allocated instead to sustain either one bison, seven to eight deer, more than two elk, nearly eleven pronghorn, nearly seven bighorn sheep, or more than one moose—not to mention that it could serve as hiding cover for sage-grouse and a buffet for butterflies and other pollinators.

Fewer domestic livestock on public lands would mean fewer wolves killed to protect livestock.

As a fraction of the nation’s beef supply, the contribution of public lands is very minor, and the market wouldn’t miss anything if livestock grazing ended on public lands.

Figure 7. Livestock near Beatty Butte in Oregon. The average full-grown cow (left) weighs ~1,400 pounds. On BLM land, the calves dine for free. Source: George Wuerthner.

A Fair Quid for the Quo

In Wyden’s Owyhee bill, the price local public lands ranchers would to pay for their “flexible” grazing language is 1.1 million acres of wilderness. In the Barrasso-Wyden flexible grazing bill, the price public lands ranchers have to pay is nada, zero, zip, zilch.

Were the Wyden site-specific (Owyhee) quid pro quo expanded nationally in the same proportion, public lands ranchers would have to accept 34,937,664 acres (but who’s counting?) of new wilderness areas. However, the Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language is at least ten times worse than the Wyden (Owyhee) “flexibility” language, so make that 349,376,649 acres of new congressional conservation designations.

Alternatively, the quid for the quo (or the quo for the quid, depending upon your point of view) could be a new title for S.4454 that provides for a nationwide voluntary grazing permit relinquishment program. (See my three Public Lands Blog posts on the subject under “For More Information” below.) There is such legislation pending in the House of Representatives, the Voluntary Grazing Permit Retirement Act (H.R.6314, 118th Congress). Wyden has successfully legislated voluntary grazing permit retirement language in legislation establishing the Soda Mountain Wilderness and expanding the Oregon Caves National Monument.

If I were one of those twenty-two elite federal grazing permittees in Malheur County, I’d be urging my buds to walk away from Wyden’s wilderness–flexible grazing bill and run toward his national flexible grazing bill. Why pay when one doesn’t have to? Especially since it would be ten times better at zero cost.

The Wyden (Owyhee) “flexible” grazing language is acceptable to much of the conservation community in the context of a quid pro quo for wilderness designation. The Barrasso-Wyden “flexible” grazing language is not accompanied by even 1 acre of congressional conservation designations such as wilderness, national monuments, national parks, national wildlife refuges, or national conservation areas. Wyden should walk away from this quid pro nihilo.

Figure 8. Livestock in the Agua Fria (“Cold Water”) National Monument in Arizona. To an untrained eye, the foreground might look “natural.” Actually, it is quite cow-bombed. Source: George Wuerthner.

For More Information

Kerr, Andy. December 2, 2016. A Federal Public Lands Grazing “Right”: No Such Animal. Public Lands Blog.

———. May 26, 2017. The High Cost of Cheap Grazing. Public Lands Blog.

———. August 13, 2021. Where’s the Beef? Public Lands Blog.

———. October 3, 2022. Senator Wyden’s Owyhee Wilderness, and More, Legislation. Public Lands Blog.

———. September 4, 2023. Retiring Grazing Permits, Part 1: Context and Case for the Voluntary Retirement Option. Public Lands Blog.

———. September 12, 2023. Retiring Grazing Permits, Part 2: History of the Voluntary Retirement Option. Public Lands Blog.

———. September 12, 2023. Retiring Grazing Permits, Part 3: Future of the Voluntary Retirement Option. Public Lands Blog.

Western Watersheds Project et al. June 26, 2024. Letter to Subcommittee on Public Lands, Forests and Mining in re S.3322 and S.4454 (118th Congress).

Bottom Line: Senator Wyden should remove his name as a cosponsor of S.4454.

Figure 9. Dead livestock in the Sonoran Desert National Monument in Arizona. Source: George Wuerthner.

The White House is very interested in protecting Oregon’s Owyhee Canyonlands as a national monument before the end of Biden’s first administration. However, President Biden won’t proceed without the all-clear from Oregon’s two US senators. Your help needed. Now.

Read MoreWhen political realities come up against ecological realities, the former must be changed because the latter cannot.

Read MoreThe O&C Lands Act of 1937 should be repealed by Congress and all BLM lands in western Oregon to either the Forest Service or the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Read MoreBLM lands in western Oregon are special in fact, but not in law. The Clearcut’s Conspiracy’s gambit to exalt the O&C lands for timber above all else failed.

Read MoreBy letting stand two federal appeals court decisions, the US Supreme Court dealt a body blow—fatal, we can hope—to the Clearcut Conspiracy’s fantasy of holtz über alles (“timber above everything else”) on ~2.1 million acres of federal public forestland in western Oregon.

Read MoreThis is the first in a series of four Public Lands Blog posts regarding the infamous “O&C” lands, a variant of public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management in western Oregon. Part 1 sets the stage with a brief history and description of recent epochal events. Part 2 examines a recent ruling by the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Part 3 examines a recent ruling by the US District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals. Part 4 recommends repeal of the O&C Lands Act of 1937 and transferring administration of all BLM lands in western Oregon to either the Forest Service or the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Top Line: By letting stand two federal appeals court decisions, the US Supreme Court dealt a body blow—fatal, we can hope—to the Clearcut Conspiracy’s fantasy of holtz über alles (“timber above everything else”) on ~2.1 million acres of federal public forestland in western Oregon.

Figure 1. A rather small locomotive of the Oregon and California Railroad. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Ever since I began my public lands conservation career during the Ford administration, a congressional statute enacted in 1937 “relating to the revested Oregon and California Railroad and reconveyed Coos Bay Wagon Road grant lands situated in the State of Oregon” has been the bane of my existence. In the mid-1970s, I discovered that the low-elevation old-growth-forested federal public lands just a few miles from where I grew up—and another 2.1 million acres administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in western Oregon—were not just your run-of-the-mill federal public lands but rather were exalted “O&C” lands.

According to my sources at the time, the O&C lands were the result of an Act of Congress so special that it effectively served as an 11th Commandment and a 26th (now 28th) Amendment. In all matters, the timber supremacy of the Oregon and California Lands Act (OCLA) of 1937 ruled! My sources of this information were the BLM, Big Timber, the western Oregon counties that received three-quarters of the timber revenues from the clear-cutting of old-growth forests (hereafter Addicted Counties), and all of Oregon’s congressional delegation (all collectively hereafter the Clearcut Conspiracy). Notice that I don’t list the judiciary as a source at that time—more on that later.

From 1937 until 1990, the Clearcut Conspiracy was successful with its holtz über alles narrative. Since the 1990s, especially during Democratic administrations, the BLM is no longer part of the conspiracy, but the agency still loves to log mature and old-growth forests and uses the OCLA as both a sword and a shield. Today, most members of the Oregon congressional delegation are not members of the Clearcut Conspiracy. The two unreconstructed holdouts are Representatives Cliff Bentz (R-OR-2nd) and Val Hoyle (D-OR-4th). (As to the latter, see this C-SPAN video [starting at 1:17:50] where Hoyle parrots the Clearcut Conspiracy’s talking points.)

Figure 2. The bane of my existence. Source: United States of America.

A Brief Synopsis of the O&C Lands

In 1866 Congress granted 3.7 million acres of public domain lands in western Oregon to facilitate the construction of a railroad from Portland to the California border. The Oregon and California Railroad line was built south as far as Medford before running out of money, at which point Southern Pacific Railroad took it over and finished the line into California.

Southern Pacific also sold huge blocks of the granted land to timber speculators. This violated the terms of the land grant, which specified the land could be sold only to bona fide settlers in 160-acre parcels for no more than $2.50 per acre. A series of lawsuits ensued, and eventually the Supreme Court directed that the granted lands that had not already been sold by the railroad into private ownership be returned to the government.

In 1916, Congress took back (after paying the Southern Pacific for them) the unsold 2.8 million acres of granted land and placed them under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office of the Department of the Interior. It further required that the General Land Office clear-cut these “Oregon and California Railroad Revested Lands” (a.k.a. O&C lands) as rapidly as possible and then sell first the timber and then the logged-off lands at auction.

Mostly the lands just remained in political and policy limbo, and in 1937 Congress enacted the Oregon and California Revested Lands Act (OCLA), a statute to retain in federal ownership the 2.7 million acres of land that were still unsold and manage them for multiple forest products (not just timber). The law also compensated sixteen western Oregon counties that could no longer collect property taxes on these again-federal lands.

The stage was set. Between 1937 and 1989, the Bureau of Land Management, successor to the General Land Office, and the rest of the Clearcut Conspiracy interpreted the 1937 statute as holtz über alles. Vast swaths of generally low-elevation old-growth forest were clear-cut and replaced with monoculture plantations of Douglas-fir.

Map 1. O&C lands administered by the BLM (dark orange), mostly in a checkerboard pattern with private timberland (white), some in a checkerboard pattern with BLM public domain land (yellow); “controverted” O&C lands administered by the US Forest Service (dark green), mostly in a checkerboard pattern with regular USFS lands (light green); Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands administered by the BLM (burgundy). Source: Congressional Research Service.

In the early 1990s, multiple lawsuits to protect the northern spotted owl and other species resulted in dramatic drop-offs in O&C logging levels and payments to counties.

In 1995, President Clinton issued the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP), which kept logging levels relatively low.

In 2016, the BLM abandoned the NWFP and continued with a management regime that resulted in the loss of mature and old-growth forests and trees but also kept logging levels relatively low compared to historical levels. The Clearcut Conspiracy (which the BLM and much of the Oregon congressional delegation were no longer a part of) sued.

In 2000, President Clinton proclaimed, pursuant to the Antiquities Act of 1906, the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, which included some infamous O&C lands. The Clearcut Conspiracy did not challenge the proclamation. In 2017, President Obama expanded the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument to include more O&C lands. This time, the Clearcut Conspiracy did sue.

In 2024, the US Supreme Court let stand two 2023 decisions from two federal courts of appeal that found the Clearcut Conspiracy’s lawsuits to reimpose holtz über alles were without merit because that interpretation of the OCLA was wrong all along.

For more details on the history of the infamous O&C lands, see my Public Lands Blog post “Another Northwest Forest War in the Offing? Part 1: A Sordid Tale of Environmental Destruction, Greed, and Political Malfeasance.”

Figure 3. Old-growth logs are still coming off BLM holdings in western Oregon. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

The Lands at Issue

There are three variants of the “O&C” lands (Map 1):

1. O&C lands administered by the BLM, mostly in a checkerboard pattern with private timberland, some in a checkerboard pattern with BLM public domain land.

2. “Controverted” O&C lands administered by the US Forest Service (USFS), mostly in a checkerboard pattern with regular USFS lands.

3. Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands administered by the BLM.

Under contention in the Clearcut Conspiracy suits were 2,084,884 acres of BLM O&C lands, lands revested from the land-grant-violating railroad. Also contested were the 74,547 acres of CBWR lands (Map 2), similarly reconveyed to the federal government for similar reasons at a similar time and administered the same as the O&C lands.

Map 2. The Coos Bay Wagon Road Lands, an even more obscure variant of federal public lands administered by the BLM.Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Somewhat in the mix, as they are intermixed with BLM O&C lands, were 394,578 acres of BLM generally forested public domain lands in western Oregon, lands that have never left the federal estate. For a long while, the BLM treated these western Oregon public domain lands the same as it treated its O&C lands.

Not under legal contention were the 492,000 acres of Forest Service O&C land shown in Map 1, which are national forest lands in every way except that counties benefit from these lands according to the O&C revenue-sharing formula rather than the regular national forest revenue-sharing formula.

Timber Above All Else?

It has long been the contention of the Clearcut Conspiracy that the OCLA outranks any other congressional statute, enacted prior or subsequent to 1937. Let’s drill down on that contention and see how the judiciary has responded. A basic rule of judicial interpretation of statutory construction is that if Congress intended a new statute to negate an existing statute, it would either repeal the older statute or explicitly say that it didn’t apply where the new statute applied. In a series of court cases from 1990 through the present, the judiciary has found that the OCLA doesn’t outrank other laws—especially, but not exclusively, those congressional statutes enacted after 1937.

Take, for example, these statutes subsequent to the OCLA of 1937: the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 (APA), the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 (NEPA), the Clean Water Act of 1970 (CWA), and the Endangered Species Act of 1972 (ESA) (all as amended). If Congress had meant to exempt the O&C lands from those later statutes, it would have said so when it enacted those statutes. Congress did not. Yet it took a series of court cases, starting in 1989, to conclude that APA, NEPA, CWA, and ESA all apply to O&C lands.

As for laws enacted prior to 1937, let’s consider the Antiquities Act of 1906, in which Congress granted power to the president to proclaim national monuments on federal lands. The Clearcut Conspiracy claimed that the OCLA precluded the proclamation of national monuments on any O&C lands that had any timber on them. Most recently, the courts found that the Antiquities Act does indeed apply to O&C lands. (See my previous Public Lands Blog post, “Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument: Safe from Big Timber, Threatened by the BLM.)

In only one statute, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) (as amended), did Congress address how that statute and the OCLA were to be reconciled. Section 701(b) of FLPMA says that the OCLA prevails over FLPMA “in the event of conflict with or inconsistency between this act and [the OCLA] . . . insofar as they relate to management of timber resources.” Then senior Oregon US senator Mark O. Hatfield (see my Public Lands Blog post “Mark Odom Hatfield, Part 1: Oregon Forest Destroyer”) made sure that this clause was included in FLPMA. Hatfield won and old forests lost.

Figure 4. The northern spotted owl, which requires old-growth forests for its survival. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

What Does the OCLA Actually Require?

What does the OCLA require of the BLM insofar as the 1937 statute relates to the “management of timber” on O&C lands? Remarkably, the courts had never clearly ruled on whether the OCLA itself contains an holtz über alles mandate. Between the BLM’s revising of western Oregon resource management plans in 2016 and President Obama’s expanding the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument in 2017, the Clearcut Conspiracy went all in on a judicial strategy to, once and for all, determine that (1) the OCLA is exalted above all other statutes, and (2) the OCLA is understood as stipulating that logging should reign supreme over all other uses.

Over the many decades since 1937, the BLM’s own lawyers (“solicitors”) have opined to varying degrees at various times that the OLCA is a “dominant use” statute where logging is superior to other uses, rather than a multiple use statute where timber supply is one use equal to the other named uses of protecting watersheds, regulating stream flow, contributing to local economic stability, and recreation. In its 2016 plan revisions, the BLM essentially still interpreted the OCLA as timber first—but tempered by all those other congressional statutes, in particular ESA and CWA (but not FLPMA).

The Clearcut Conspiracy’s legal blitzkrieg consisted of a total of six lawsuits, five of which were filed in the US District Court for the District of Columbia. As the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit explains:

The appeals arise from three sets of cases filed by an association of fifteen Oregon counties and various trade associations and timber companies. Two of the cases challenge Proclamation 9564, through which the President expanded the boundaries of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Two others challenge resource management plans that the United States Bureau of Land Management (BLM), a bureau within the United States Department of the Interior (Interior), developed to govern the use of the forest land. The final case seeks an order compelling the Interior Secretary to offer a certain amount of the forest’s timber for sale each year.

The Clearcut Conspiracy won all five cases filed in the District of Columbia at the district court level, where the conspiracy had successfully shopped for a favorable judge, but then lost all on appeal to the appeals court.

As for the sixth lawsuit, the Murphy Company and Murphy Timber Investments, LLC, filed suit in the US District Court for the District of Oregon contesting the expansion of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Murphy lost at the district court level and also in the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Clearcut Conspiracy was left with just one more option: a hail-Mary pass to the nine members of the US Supreme Court seeking review of the six cases it lost. The Supremes declined. As I speculated previously, perhaps the destructive majority on the court felt that this O&C matter was small beer compared to all the other potential damage they want to do.