Like bankruptcy, the death of the Northwest Forest Plan has proceeded slowly and might end quickly.

Read MoreThe Demise of Northwest Forest Plan

Federal Lands

Like bankruptcy, the death of the Northwest Forest Plan has proceeded slowly and might end quickly.

Read MoreThe new administration believes that unless it can be sold or collateralized, it has no value.

Read MoreTop Line: America’s national forests have lost the greatest inside champion they’ve ever had.

Figure 1. Jim Furnish, 1945–2025. Source: LinkedIn.

I’ve interacted with hundreds of Forest Service employees since I began agitating for wilderness designation of national forest roadless areas in 1975. Of all those hundreds of Forest Service employees, only two really impressed me. Both were forest supervisors on national forests in Oregon. Both were one of a kind. In the end, the Forest Service bureaucracy rejected both.

One was Bob Chadwick, whose star shone brightest while he was supervisor of the Winema National Forest in south-central Oregon in the late 1970s. Bob died in 2015.

The other was Jim Furnish, retired (not really by his choice) deputy chief of the Forest Service. Furnish died on January 11 at his home in New Mexico at age seventy-nine. I knew he was sick but didn’t know how sick. He was on my list to do a “preremembrance” for, essentially a eulogy that the eulogized can read themselves. Alas, procrastination and denial on my part prevented me from telling Jim how much he moved the conservation needle during his life and career, so this remembrance will belatedly honor his enormous contribution.

Backdrop: The Forest Service Culture

When I started my wilderness activism, almost all Forest Service employees I met wore metaphorical green underwear underneath their green uniforms. They believed in the agency’s mission at the time: converting “decadent” and “overmature” old-growth forests into thrifty and vigorous monoculture plantations. (I’m pretty confident today that green underwear is a thing of the past in that it is rare to see Forest Service line officers wearing their green outerwear at all.)

The way one advanced in the Forest Service as a line officer (a district ranger reported to a national forest supervisor who reported to a regional forester who reported to “the chief”) was to “get the cut out.” When a “smokey” (Forest Service employee) said “the chief,” their tone of voice changed perceptibly to invoke reverence. Just about every district ranger secretly saw themselves as “the chief,” and all figured they had a good chance of being a regional forester someday.

There is a change that occurs among Forest Service line officers when they realize they won’t ever become “the chief.” Most respond by caring less and riding out their years in the Forest Service until pension time. A few (alas, very few), however, find the realization freeing.

One Exceptional Forester: Bob Chadwick

One of those exceptions was Bob Chadwick. On the Winema, Chadwick acted upon four major matters: empowering women in the agency, treating the Klamath Tribes (from whom much of the Winema was purchased) better, reintroducing fire into fire-dependent ecosystems, and—most dangerously—lowering “the cut” (the planned-for annual timber volume sold). In re the latter, Chadwick sought to protect roadless areas and dramatically lower logging levels.

Alas, this very bright star was soon extinguished. For “the good of the service,” Forest Supervisor Chadwick was “promoted” to be an “executive assistant” to the regional forester in Portland, a position that did not exist before or after Chadwick’s tenure. He was basically told to count paper clips and keep quiet. Instead, Chadwick continued to promote his idea of consensus as a better way to manage public land. He soon left the Forest Service and continued on as a consultant until he died in 2015. Bob was way ahead of his time and the Forest Service crushed him.

Another Exceptional Forester: Jim Furnish

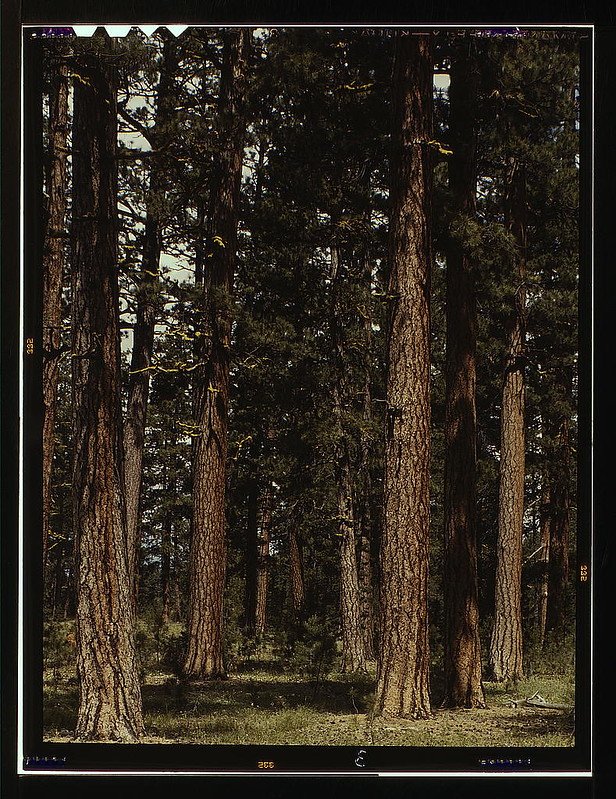

Jim Furnish was in charge of the National Forest System from 1999 to 2002. During his tenure, he was the primary author of the Roadless Area Conservation Rule, over the objections of almost every Forest Service line officer save the top line officer, who was the only one who counted, Chief Mike Dombeck. The roadless rule, covering 58 million acres of the National Forest System’s 193 million acres, prohibits road building and almost all kinds of logging there. (Alas, some loopholes exist.) Before becoming deputy chief, Furnish transformed the Siuslaw National Forest in Oregon’s Coast Range from one of the most heavily logged national forests anywhere to one of the least logged.

Born in Tyler, Texas, Furnish got his first Forest Service job as a seasonal on the Tiller Ranger District of the Umpqua National Forest. As it was 1965 and I was in the fourth grade, our paths didn’t cross until later, when he became forest supervisor of the Siuslaw National Forest, headquartered in Corvallis, from 1991 to 1999.

In between he was a forester on the Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota, a district ranger on the Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming, a staff officer on the San Juan National Forest in Colorado, and appeals coordinator in the chief’s office in Washington, DC. After supervising the Siuslaw, Furnish was appointed deputy chief over the heads and objections of all nine regional foresters, who figured the job should have gone to them.

Furnish’s Tenure on the Siuslaw as an Agency Reformer

Furnish first came to the Siuslaw as deputy supervisor in 1991 and soon was appointed supervisor. The Siuslaw, like most national forests, was in turmoil. It was the home of both reformers who could see the forest beyond the logs-to-be and some severely unreconstructed timber beasts who sang “Timber über alles” coming and going from work, during work, and in their dreams. One Siuslaw wildlife biologist told me in the late 1980s that the only good biologists in the Forest Service were assholes. (Charlie was one of them; I loved him for it.)

Soon after becoming supervisor, Furnish forced four of the biggest timber assholes out of his office; three were given early retirement and one took a demotion.

Things began to change on the Siuslaw. The reformer Furnish soon benefited from a huge tailwind in the form of a federal court injunction against essentially all federal logging within the range of the northern spotted owl. The Pacific Northwest forest wars had gone from guerilla skirmishes to epic set-piece battles.

It was a good time to be an agency reformer. As Furnish later wrote in his memoir, Toward a Natural Forest: The Forest Service in Transition:

Prior to Judge Dwyer’s ruling, the Forest Service had inexorably, incrementally sought to tame the vast and valuable forests of the Pacific Northwest. Aggressive logging of public land rested on a foundation of a growing nation’s demand for wood. And the nation trusted the Forest Service as long as its policies seemed consistent with public values. But public values can change. Distrust can grow.

Following the war in Vietnam, a new generation viewed government with increasing skepticism and cynicism. Fewer and fewer people accepted sweeping vistas dominated by clear-cuts and new roads. Instead, they valued naturalness, clean water, abundant fish and wildlife, and a deep sense of connection with the land. They were anguished at what the Forest Service was taking from the forest at the expense of future generations.

You can plant all the trees you want, but you can’t make a forest. That’s God’s business.

Figure 2. Any reforming Forest Service employee today should read Furnish’s memoir. So too should the reconstructed (no longer unreconstructed, but still) timber beasts, who should ask themselves if anyone would bother to read their memoir if they bothered to write one. Source: Oregon State University Press.

By the way, most retired line officers in the Forest Service hated Jim Furnish, as they had made their careers by being timber beasts. Furnish was a messenger they wanted to shoot before, during, and after a district court judge and a US president told the Forest Service to obey the law.

During his tenure on the Siuslaw, Furnish did many remarkable things, but we shall focus here on timber, roads, and fish.

Changing Timber Targets

When Furnish got to the Siuslaw, the new forest plan set a target of 215 million board feet (mmbf) annually, down from 320 mamba throughout the 1980s.

(A programmed timber target was one thing; the agency was in the habit of even more logging in the name of salvage, etc. I remember the actual annual losses reaching in excess of 450 mamba. I remember that particular number because it was what Congress required the Forest Service to annually sell from the Tongass National Forest in Alaska under a law passed in 1980. The Siuslaw has 623,000 acres, while the Tongass has more than 15 million acres—equal to all national forest land in Oregon.)

President Clinton’s Northwest Forest Plan dropped the timber target on the Siuslaw to 23 mmbf from 215 mmbf. A later remapping of riparian reserves (no-cut stream buffers with a minimum of 300 feet on each side) found there were significantly more highly dissected streams in the Oregon Coast Range than first thought, and this new analysis reduced the possible timber target to ~8 mmbf. Between the ESA-protected northern spotted owl and marbled murrelet and various imperiled stocks of Pacific salmon, almost all of the Siuslaw National Forest was protected as either late-successional (mature and old-growth forest) reserves or riparian reserves, respectively.

Furnish directed the logging that could be done on the Siuslaw to focus on 120,000 acres of plantations that were established after the mature and old-growth forest was clear-cut. On those plantations, only one species, Douglas-fir, had been planted, and herbicides were often used to ensure nothing competed. The result was Douglas-fir plantations of even height and even spacing, more akin to a cornfield than a forest.

Under Furnish the Siuslaw went big on variable-density thinning, which had the objective of putting the plantations on a path to once again become mature and old-growth forests. As trees in Oregon’s Coast Range grow almost all year and generally in good soils, the logs that came from such thinning were commercially valuable to those mills that had retooled away from old growth. Most had. Not as profitable as liquidating old growth, but that ship had sailed.

Closing Roads and Helping Fish

By the time the spotted owl hit the fan in 1990 and the injunction was imposed, the Siuslaw had 2,700 miles of roads—2.7 miles of road for every square mile of land. Under Furnish, two-thirds of all the roads were closed to the public, relieving the federal treasury of the road maintenance burden and relieving wildlife of all those intrusions on what they called home.

Most Siuslaw timber roads were engineered enough to get the big logs out and to the mill but not to endure during massive storm events. Their damned culverts were engineered to allow big logs to pass over them but neither large amounts of water and large woody debris during big storm events nor fish to pass through them.

Under Furnish, the Siuslaw embarked on a massive program of making the roads hydrologically invisible to the watershed, primarily by doing two things: (1) ripping out undersized culverts to allow water and debris to flow freely, and (2) water barring the roads so the water falling on the road very soon was flowing downhill off the road and not into undersized ditches that fed those undersized culverts. The Siuslaw staff compared water-barred and un-water-barred roads, and the barred roads didn’t erode into huge landslides into creeks.

The result was improved water quality, restored fish passage, and enhanced fish habitat.

After the Fall

After leaving the Forest Service, Furnish continued to agitate from without as he had done from within. In his “retirement,” he served on the boards of several organizations, including WildEarth Guardians, Wildlands CPR, Geos Institute, and Evangelical Environmental Coalition. He was also a close advisor of the Climate Forest Campaign. He helped focus media attention on mature and old-growth forests everywhere and in particular on the Forest Service mismanaging (overcutting) his beloved Black Hills National Forest in South Dakota.

Furnish summed up his tenure at the Forest Service thusly: “The spotted owl crisis, and my years on the Siuslaw National Forest, offered many circumstances and opportunities to confront troubling realities and foster profound change.”

Thank you, Jim.

Bottom Line: Jim Furnish illustrated that although it is far too rare, a person can enter the federal bureaucracy and lease as a public servant who changed it for the better.

For More Information

American Forests. February 2, 2016. Jim Furnish, retired deputy chief, USDA Forest Service (web page).

Family of Jim Furnish. 2025. Official Obituary of James “Jim” Richards Furnish.

Furnish, Jim. 2015. Toward a Natural Forest: The Forest Service in Transition. Oregon State University Press, Corvallis.

Heller, Marc. January 14, 2025. “Logging limits pioneer dies at 79.” Greenwire.

Utah’s lawsuit against the United States is an existential threat to more than 200 million acres of federal public lands.

Read MoreThe reduction of surplus production capacity continues to result in lumber mill shutdowns, though the contributing factors cited have changed as times have changed.

Read MoreTop Line: Senator Wyden is cosponsoring legislation that would give blank checks and get-out-of-jail-free cards to all BLM grazing permittees and lessees.

Figure 1. A bovine on public lands crapping in the same stream from which it drinks. In the absence of domestic livestock, this stream would be colder and deeper, well shaded by willows if not also cottonwoods, and likely full of trout. Source: George Wuerthner.

Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) is the sole cosponsor of a bill by Senator John Barrasso (R-WY) that would give Bureau of Land Management (BLM) grazing permittees and lessees even more free rein than they have now to (ab)use the public lands. The Barrasso-Wyden bill, the Operational Flexibility Grazing Management Program Act (S.4454, 118th Congress), would effectively remove any administrative control the BLM has over the grazing of livestock on 155 million acres of federal public lands.

As a senator from Wyoming, Barrasso has long carried any and all water requested of him by public lands grazing permittees and lessees. The Barrasso-Wyden bill is the latest in a long line.

Wyden’s Proposed Owyhee Canyonlands Bill: Quid Pro Quo

This is not Wyden’s first legislative attempt on behalf of grazing “flexibility.”

For the past several years, Senator Wyden and his staff have labored long and hard to bring forth legislation to address public land management issues in Malheur County, Oregon. The latest incarnation of his Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act, would primarily do two things on BLM holdings in Malheur County:

• Establish ~1.1 million acres of new wilderness areas.

• Authorize “flexible” livestock grazing on BLM lands in Malheur County.

The bill would do other things, but most of the verbiage pertains to wilderness and livestock grazing.

Wyden’s bill proposing a wilderness–livestock grazing grand bargain in the Owyhee Canyonlands (S.1890; 118th Congress), was introduced in the Senate in June 2023, reported out of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee in December 2023. A vote of the full Senate has not been scheduled. Most, but not all, of the conservation community supports S.1890 and they feel it is—despite a grazing “flexibility” provision—a significant net gain for public lands conservation.

Figure 2. Land near Kemmerer, Wyoming. On one side of the fence, the land is ungrazed. Guess which side. Source: George Wuerthner.

Here are two political givens:

• Conservationists love wilderness and hate livestock grazing.

• Public lands ranchers love livestock grazing and hate wilderness.

However, there is a place where these two sets overlap (picture a Venn diagram), and Wyden has found it in his Owyhee bill. Public lands ranchers really want “flexibility” language and are willing to give 1.1 million acres of wilderness to get it. Conservationists really want 1.1 million acres of wilderness and are willing to give a carefully worded and constrained version of grazing “flexibility.”

In the crafting and politics of legislation, such is known as a quid pro quo. One faction gets something they want more by accepting something they want less. Happens all the time.

The proposed wilderness boundaries and grazing language were long debated and fought over, but Wyden’s latest bill seems to thread a political needle.

In cosponsoring S.4454, Wyden has tossed aside the delicate compromise offered in his Owyhee legislation and embraced a unilateral and far more damaging giveaway to the public lands livestock industry.

Figure 3. Livestock in the Sonoran Desert National Monument in Arizona. Source: George Wuerthner.

The Entrails of the Barrasso-Wyden Bill: Quid Pro Nihilo

“Flexible” grazing is not bovines practicing their yoga cow pose.

It would be bad enough if Wyden had taken his Owyhee “flexibility” language national and offered it without any corresponding conservation (a.k.a. “wilderness”) offset. However, the Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language is arguably ten times worse in effect than the Wyden (Owyhee) “flexibility” language.

The Wyden (Owyhee) version of “flexible” grazing contains sideboards and leaves public lands managers with their ability to manage grazing on public lands. The Barrasso-Wyden (national) version of “flexible” grazing means that public lands ranchers get to do even more of what they want on public lands, with the public lands managers no longer having a say, with no analysis and stewardship requirements.

The Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language is a total giveaway of blank checks and get-out-of-jail-free cards to grazing permittees and lessees on public lands administered by the BLM.

Figure 4. Livestock near the Paria River in the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument in Utah. I honestly don’t know what they are eating. Source: George Wuerthner.

The public policy director for the Western Watersheds Project (WWP), Josh Osher (my go-to guy for all matters of public lands grazing policy), submitted testimony (on behalf also of Kettle Range Conservation, Oregon Natural Desert Association, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, and Wilderness Watch) in opposition to the Barrasso-Wyden bill (WWP et al.). The bottom line:

S. 4454 is an attempted end around to virtually eliminate NEPA requirements and public involvement in grazing management on public lands. This bill puts all of the power in the permittee’s hands and removes nearly all discretion from the Secretary to manage grazed lands for multiple use. Passage of S. 4454 would lead to continued failure of BLM managed lands to meet even the most basic standards for land health and eliminate the few remaining tools at the BLM’s discretion to address problematic livestock grazing. [emphasis added]

How does the Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language compare to the Wyden (Owyhee) “flexibility” language? The WWP letter notes:

Furthermore, this legislation is a significant departure from the current pilot program initiated by the BLM and the operational flexibility language in S. 1890, the Malheur Community Empowerment for the Owyhee Act. S. 4454 dramatically expands the purposes for modifying the terms and conditions of grazing permit from responses to environmental factors and ecological conditions to now include producer preferences and responsiveness to market conditions. [emphasis added]

The Barrasso-Wyden “flexibility” language would make a complete sham of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) by requiring the BLM to always choose the “flexible” grazing alternative. The WWP letter notes:

The bill language states that the “Secretary shall develop and authorize at least 1 alternative” for operational flexibility. It is unclear if “authorize” means that alternative must be chosen or simply analyzed with the discretion remaining with the Secretary to determine which alternative to implement. If the former, this a complete usurpation of the Secretary’s authority to manage public lands according to multiple use principles. [emphasis in original]

The WWP letter further notes:

The final section that prohibits termination of a grazing permit due to the use of operational flexibility functions to fully insulate the permittee from any consequences of bad management choices for which the Secretary had no discretion to modify or deny. [emphasis added]

In reading legislation, I always try to follow two principles:

• Read the language as if you are paranoid. Read the language in a way that the forces of darkness could/would interpret it if they were in charge. Just because one is paranoid, it doesn’t mean that one is not being followed.

• Clearly discern what is being done for you and what is being done to you in the legislative language. The Barrasso-Wyden bill is all the latter and none of the former.

Rather than an acceptable quid pro quo, the Barrasso-Wyden “flexibility” language is a quid pro nihilo (something for nothing). Something for public lands ranchers, nothing for conservationists.

Figure 5. Livestock in the Eagletail Mountains in Arizona. Source: George Wuerthner.

A Benign Bovine: No Such Animal

Let’s take a moment to remind ourselves why livestock production—especially on public lands—is problematic.

Domestic livestock have done, and are doing, more damage to Earth than the chainsaw and bulldozer combined.

Livestock production—primarily cows—accounts for 14.5 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions (a few sources say less, most sources say more), most in the form of methane emitted by belching bovines. A molecule of methane has a global warming potential at least 28 times greater than that of a molecule of carbon dioxide. Animal agriculture also produces 65 percent of the world’s emissions of nitrous oxide (yes, laughing gas, but no laughing matter here), which has a global warming potential 296 times greater than that of carbon dioxide. In addition, 70 percent of the world’s agricultural lands are dedicated to livestock—lands that were formerly forests, grasslands, and/or wetlands.

Locally—and most especially on public lands—livestock cause chronic and grievous environmental harm. Most streams flowing through public lands have been cow-bombed to such an extent that water quality is horrendous and water quantity is diminished.

Figure 6. Fresh cow shit on rocks in a stream on public lands. If it were deposited on land, many would call it a cow pie. I do not. Unlike pie, cow shit is neither sweet nor savory. Source: George Wuerthner.

The public land forage now consumed by one cow and one calf could be allocated instead to sustain either one bison, seven to eight deer, more than two elk, nearly eleven pronghorn, nearly seven bighorn sheep, or more than one moose—not to mention that it could serve as hiding cover for sage-grouse and a buffet for butterflies and other pollinators.

Fewer domestic livestock on public lands would mean fewer wolves killed to protect livestock.

As a fraction of the nation’s beef supply, the contribution of public lands is very minor, and the market wouldn’t miss anything if livestock grazing ended on public lands.

Figure 7. Livestock near Beatty Butte in Oregon. The average full-grown cow (left) weighs ~1,400 pounds. On BLM land, the calves dine for free. Source: George Wuerthner.

A Fair Quid for the Quo

In Wyden’s Owyhee bill, the price local public lands ranchers would to pay for their “flexible” grazing language is 1.1 million acres of wilderness. In the Barrasso-Wyden flexible grazing bill, the price public lands ranchers have to pay is nada, zero, zip, zilch.

Were the Wyden site-specific (Owyhee) quid pro quo expanded nationally in the same proportion, public lands ranchers would have to accept 34,937,664 acres (but who’s counting?) of new wilderness areas. However, the Barrasso-Wyden (national) “flexibility” language is at least ten times worse than the Wyden (Owyhee) “flexibility” language, so make that 349,376,649 acres of new congressional conservation designations.

Alternatively, the quid for the quo (or the quo for the quid, depending upon your point of view) could be a new title for S.4454 that provides for a nationwide voluntary grazing permit relinquishment program. (See my three Public Lands Blog posts on the subject under “For More Information” below.) There is such legislation pending in the House of Representatives, the Voluntary Grazing Permit Retirement Act (H.R.6314, 118th Congress). Wyden has successfully legislated voluntary grazing permit retirement language in legislation establishing the Soda Mountain Wilderness and expanding the Oregon Caves National Monument.

If I were one of those twenty-two elite federal grazing permittees in Malheur County, I’d be urging my buds to walk away from Wyden’s wilderness–flexible grazing bill and run toward his national flexible grazing bill. Why pay when one doesn’t have to? Especially since it would be ten times better at zero cost.

The Wyden (Owyhee) “flexible” grazing language is acceptable to much of the conservation community in the context of a quid pro quo for wilderness designation. The Barrasso-Wyden “flexible” grazing language is not accompanied by even 1 acre of congressional conservation designations such as wilderness, national monuments, national parks, national wildlife refuges, or national conservation areas. Wyden should walk away from this quid pro nihilo.

Figure 8. Livestock in the Agua Fria (“Cold Water”) National Monument in Arizona. To an untrained eye, the foreground might look “natural.” Actually, it is quite cow-bombed. Source: George Wuerthner.

For More Information

Kerr, Andy. December 2, 2016. A Federal Public Lands Grazing “Right”: No Such Animal. Public Lands Blog.

———. May 26, 2017. The High Cost of Cheap Grazing. Public Lands Blog.

———. August 13, 2021. Where’s the Beef? Public Lands Blog.

———. October 3, 2022. Senator Wyden’s Owyhee Wilderness, and More, Legislation. Public Lands Blog.

———. September 4, 2023. Retiring Grazing Permits, Part 1: Context and Case for the Voluntary Retirement Option. Public Lands Blog.

———. September 12, 2023. Retiring Grazing Permits, Part 2: History of the Voluntary Retirement Option. Public Lands Blog.

———. September 12, 2023. Retiring Grazing Permits, Part 3: Future of the Voluntary Retirement Option. Public Lands Blog.

Western Watersheds Project et al. June 26, 2024. Letter to Subcommittee on Public Lands, Forests and Mining in re S.3322 and S.4454 (118th Congress).

Bottom Line: Senator Wyden should remove his name as a cosponsor of S.4454.

Figure 9. Dead livestock in the Sonoran Desert National Monument in Arizona. Source: George Wuerthner.

The O&C Lands Act of 1937 should be repealed by Congress and all BLM lands in western Oregon to either the Forest Service or the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Read MoreBLM lands in western Oregon are special in fact, but not in law. The Clearcut’s Conspiracy’s gambit to exalt the O&C lands for timber above all else failed.

Read MoreThis is the first in a series of four Public Lands Blog posts regarding the infamous “O&C” lands, a variant of public lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management in western Oregon. Part 1 sets the stage with a brief history and description of recent epochal events. Part 2 examines a recent ruling by the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Part 3 examines a recent ruling by the US District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals. Part 4 recommends repeal of the O&C Lands Act of 1937 and transferring administration of all BLM lands in western Oregon to either the Forest Service or the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Top Line: By letting stand two federal appeals court decisions, the US Supreme Court dealt a body blow—fatal, we can hope—to the Clearcut Conspiracy’s fantasy of holtz über alles (“timber above everything else”) on ~2.1 million acres of federal public forestland in western Oregon.

Figure 1. A rather small locomotive of the Oregon and California Railroad. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Ever since I began my public lands conservation career during the Ford administration, a congressional statute enacted in 1937 “relating to the revested Oregon and California Railroad and reconveyed Coos Bay Wagon Road grant lands situated in the State of Oregon” has been the bane of my existence. In the mid-1970s, I discovered that the low-elevation old-growth-forested federal public lands just a few miles from where I grew up—and another 2.1 million acres administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in western Oregon—were not just your run-of-the-mill federal public lands but rather were exalted “O&C” lands.

According to my sources at the time, the O&C lands were the result of an Act of Congress so special that it effectively served as an 11th Commandment and a 26th (now 28th) Amendment. In all matters, the timber supremacy of the Oregon and California Lands Act (OCLA) of 1937 ruled! My sources of this information were the BLM, Big Timber, the western Oregon counties that received three-quarters of the timber revenues from the clear-cutting of old-growth forests (hereafter Addicted Counties), and all of Oregon’s congressional delegation (all collectively hereafter the Clearcut Conspiracy). Notice that I don’t list the judiciary as a source at that time—more on that later.

From 1937 until 1990, the Clearcut Conspiracy was successful with its holtz über alles narrative. Since the 1990s, especially during Democratic administrations, the BLM is no longer part of the conspiracy, but the agency still loves to log mature and old-growth forests and uses the OCLA as both a sword and a shield. Today, most members of the Oregon congressional delegation are not members of the Clearcut Conspiracy. The two unreconstructed holdouts are Representatives Cliff Bentz (R-OR-2nd) and Val Hoyle (D-OR-4th). (As to the latter, see this C-SPAN video [starting at 1:17:50] where Hoyle parrots the Clearcut Conspiracy’s talking points.)

Figure 2. The bane of my existence. Source: United States of America.

A Brief Synopsis of the O&C Lands

In 1866 Congress granted 3.7 million acres of public domain lands in western Oregon to facilitate the construction of a railroad from Portland to the California border. The Oregon and California Railroad line was built south as far as Medford before running out of money, at which point Southern Pacific Railroad took it over and finished the line into California.

Southern Pacific also sold huge blocks of the granted land to timber speculators. This violated the terms of the land grant, which specified the land could be sold only to bona fide settlers in 160-acre parcels for no more than $2.50 per acre. A series of lawsuits ensued, and eventually the Supreme Court directed that the granted lands that had not already been sold by the railroad into private ownership be returned to the government.

In 1916, Congress took back (after paying the Southern Pacific for them) the unsold 2.8 million acres of granted land and placed them under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office of the Department of the Interior. It further required that the General Land Office clear-cut these “Oregon and California Railroad Revested Lands” (a.k.a. O&C lands) as rapidly as possible and then sell first the timber and then the logged-off lands at auction.

Mostly the lands just remained in political and policy limbo, and in 1937 Congress enacted the Oregon and California Revested Lands Act (OCLA), a statute to retain in federal ownership the 2.7 million acres of land that were still unsold and manage them for multiple forest products (not just timber). The law also compensated sixteen western Oregon counties that could no longer collect property taxes on these again-federal lands.

The stage was set. Between 1937 and 1989, the Bureau of Land Management, successor to the General Land Office, and the rest of the Clearcut Conspiracy interpreted the 1937 statute as holtz über alles. Vast swaths of generally low-elevation old-growth forest were clear-cut and replaced with monoculture plantations of Douglas-fir.

Map 1. O&C lands administered by the BLM (dark orange), mostly in a checkerboard pattern with private timberland (white), some in a checkerboard pattern with BLM public domain land (yellow); “controverted” O&C lands administered by the US Forest Service (dark green), mostly in a checkerboard pattern with regular USFS lands (light green); Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands administered by the BLM (burgundy). Source: Congressional Research Service.

In the early 1990s, multiple lawsuits to protect the northern spotted owl and other species resulted in dramatic drop-offs in O&C logging levels and payments to counties.

In 1995, President Clinton issued the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP), which kept logging levels relatively low.

In 2016, the BLM abandoned the NWFP and continued with a management regime that resulted in the loss of mature and old-growth forests and trees but also kept logging levels relatively low compared to historical levels. The Clearcut Conspiracy (which the BLM and much of the Oregon congressional delegation were no longer a part of) sued.

In 2000, President Clinton proclaimed, pursuant to the Antiquities Act of 1906, the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, which included some infamous O&C lands. The Clearcut Conspiracy did not challenge the proclamation. In 2017, President Obama expanded the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument to include more O&C lands. This time, the Clearcut Conspiracy did sue.

In 2024, the US Supreme Court let stand two 2023 decisions from two federal courts of appeal that found the Clearcut Conspiracy’s lawsuits to reimpose holtz über alles were without merit because that interpretation of the OCLA was wrong all along.

For more details on the history of the infamous O&C lands, see my Public Lands Blog post “Another Northwest Forest War in the Offing? Part 1: A Sordid Tale of Environmental Destruction, Greed, and Political Malfeasance.”

Figure 3. Old-growth logs are still coming off BLM holdings in western Oregon. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

The Lands at Issue

There are three variants of the “O&C” lands (Map 1):

1. O&C lands administered by the BLM, mostly in a checkerboard pattern with private timberland, some in a checkerboard pattern with BLM public domain land.

2. “Controverted” O&C lands administered by the US Forest Service (USFS), mostly in a checkerboard pattern with regular USFS lands.

3. Coos Bay Wagon Road (CBWR) lands administered by the BLM.

Under contention in the Clearcut Conspiracy suits were 2,084,884 acres of BLM O&C lands, lands revested from the land-grant-violating railroad. Also contested were the 74,547 acres of CBWR lands (Map 2), similarly reconveyed to the federal government for similar reasons at a similar time and administered the same as the O&C lands.

Map 2. The Coos Bay Wagon Road Lands, an even more obscure variant of federal public lands administered by the BLM.Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Somewhat in the mix, as they are intermixed with BLM O&C lands, were 394,578 acres of BLM generally forested public domain lands in western Oregon, lands that have never left the federal estate. For a long while, the BLM treated these western Oregon public domain lands the same as it treated its O&C lands.

Not under legal contention were the 492,000 acres of Forest Service O&C land shown in Map 1, which are national forest lands in every way except that counties benefit from these lands according to the O&C revenue-sharing formula rather than the regular national forest revenue-sharing formula.

Timber Above All Else?

It has long been the contention of the Clearcut Conspiracy that the OCLA outranks any other congressional statute, enacted prior or subsequent to 1937. Let’s drill down on that contention and see how the judiciary has responded. A basic rule of judicial interpretation of statutory construction is that if Congress intended a new statute to negate an existing statute, it would either repeal the older statute or explicitly say that it didn’t apply where the new statute applied. In a series of court cases from 1990 through the present, the judiciary has found that the OCLA doesn’t outrank other laws—especially, but not exclusively, those congressional statutes enacted after 1937.

Take, for example, these statutes subsequent to the OCLA of 1937: the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946 (APA), the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970 (NEPA), the Clean Water Act of 1970 (CWA), and the Endangered Species Act of 1972 (ESA) (all as amended). If Congress had meant to exempt the O&C lands from those later statutes, it would have said so when it enacted those statutes. Congress did not. Yet it took a series of court cases, starting in 1989, to conclude that APA, NEPA, CWA, and ESA all apply to O&C lands.

As for laws enacted prior to 1937, let’s consider the Antiquities Act of 1906, in which Congress granted power to the president to proclaim national monuments on federal lands. The Clearcut Conspiracy claimed that the OCLA precluded the proclamation of national monuments on any O&C lands that had any timber on them. Most recently, the courts found that the Antiquities Act does indeed apply to O&C lands. (See my previous Public Lands Blog post, “Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument: Safe from Big Timber, Threatened by the BLM.)

In only one statute, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976 (FLPMA) (as amended), did Congress address how that statute and the OCLA were to be reconciled. Section 701(b) of FLPMA says that the OCLA prevails over FLPMA “in the event of conflict with or inconsistency between this act and [the OCLA] . . . insofar as they relate to management of timber resources.” Then senior Oregon US senator Mark O. Hatfield (see my Public Lands Blog post “Mark Odom Hatfield, Part 1: Oregon Forest Destroyer”) made sure that this clause was included in FLPMA. Hatfield won and old forests lost.

Figure 4. The northern spotted owl, which requires old-growth forests for its survival. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

What Does the OCLA Actually Require?

What does the OCLA require of the BLM insofar as the 1937 statute relates to the “management of timber” on O&C lands? Remarkably, the courts had never clearly ruled on whether the OCLA itself contains an holtz über alles mandate. Between the BLM’s revising of western Oregon resource management plans in 2016 and President Obama’s expanding the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument in 2017, the Clearcut Conspiracy went all in on a judicial strategy to, once and for all, determine that (1) the OCLA is exalted above all other statutes, and (2) the OCLA is understood as stipulating that logging should reign supreme over all other uses.

Over the many decades since 1937, the BLM’s own lawyers (“solicitors”) have opined to varying degrees at various times that the OLCA is a “dominant use” statute where logging is superior to other uses, rather than a multiple use statute where timber supply is one use equal to the other named uses of protecting watersheds, regulating stream flow, contributing to local economic stability, and recreation. In its 2016 plan revisions, the BLM essentially still interpreted the OCLA as timber first—but tempered by all those other congressional statutes, in particular ESA and CWA (but not FLPMA).

The Clearcut Conspiracy’s legal blitzkrieg consisted of a total of six lawsuits, five of which were filed in the US District Court for the District of Columbia. As the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit explains:

The appeals arise from three sets of cases filed by an association of fifteen Oregon counties and various trade associations and timber companies. Two of the cases challenge Proclamation 9564, through which the President expanded the boundaries of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Two others challenge resource management plans that the United States Bureau of Land Management (BLM), a bureau within the United States Department of the Interior (Interior), developed to govern the use of the forest land. The final case seeks an order compelling the Interior Secretary to offer a certain amount of the forest’s timber for sale each year.

The Clearcut Conspiracy won all five cases filed in the District of Columbia at the district court level, where the conspiracy had successfully shopped for a favorable judge, but then lost all on appeal to the appeals court.

As for the sixth lawsuit, the Murphy Company and Murphy Timber Investments, LLC, filed suit in the US District Court for the District of Oregon contesting the expansion of the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument. Murphy lost at the district court level and also in the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Clearcut Conspiracy was left with just one more option: a hail-Mary pass to the nine members of the US Supreme Court seeking review of the six cases it lost. The Supremes declined. As I speculated previously, perhaps the destructive majority on the court felt that this O&C matter was small beer compared to all the other potential damage they want to do.

In the next two Public Lands Blog posts, I examine in detail the rulings of the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (Part 2 of this series) and the US District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals (Part 3 of this series). I go so deep on these rulings because they make clear that the Clearcut Conspiracy’s fantasy that the OCLA of 1937 is a combo 11th Commandment and 28th Amendment is and always has been just that—a fantasy.

Figure 5. An adult coho salmon scaling Lake Creek Falls to return to its place of birth to spawn. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Take a Bow

Special thanks are due to Kristen Boyles of Earthjustice and Susan Jane Brown, then mostly of the Western Environmental Law Center and now of Silvix Resources. These extraordinary lawyers represented Soda Mountain Wilderness Council and other intervenors. The several cases in two judicial circuits were as long and arduous as the stakes were high. The most able counsel of these two lawyers helped ensure that the courts eventually got it right.

For More Information

Blumm, Michael, and Tim Wigington. 2013. “The Oregon & California Railroad Grant Lands’ Sordid Past, Contentious Present, and Uncertain Future: A Century of Conflict.” Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review.

Kerr, Andy. 2020. “Another Northwest Forest War in the Offing? Part 1: A Sordid Tale of Environmental Destruction, Greed, and Political Malfeasance.” Public Lands Blog.

———. 2020. “Another Northwest Forest War in the Offing? Part 2: Current Threats and Perhaps an Epic Opportunity.” Public Lands Blog.

Riddle, Anne A. 2023. “The Oregon and California Railroad Lands (O&C Lands): In Brief.” Congressional Research Service R42951.

Robbins, William G. “Oregon and California Lands Act.” Oregon Encyclopedia.

Scott, Deborah, and Susan Jane Brown. 2006. “The Oregon and California Lands Act: Revisiting the Concept of ‘Dominant Use’.” Journal of Environmental Law and Litigation.

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. July 18, 2023. American Forest Resource Council v. United States of America.

United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. April 24, 2023. Murphy Co. v. Biden.

Big Timber’s and Addicted Counties’ supreme gambits to gut the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument have failed, but the monument is still in mortal peril from the Bureau of Land Management.

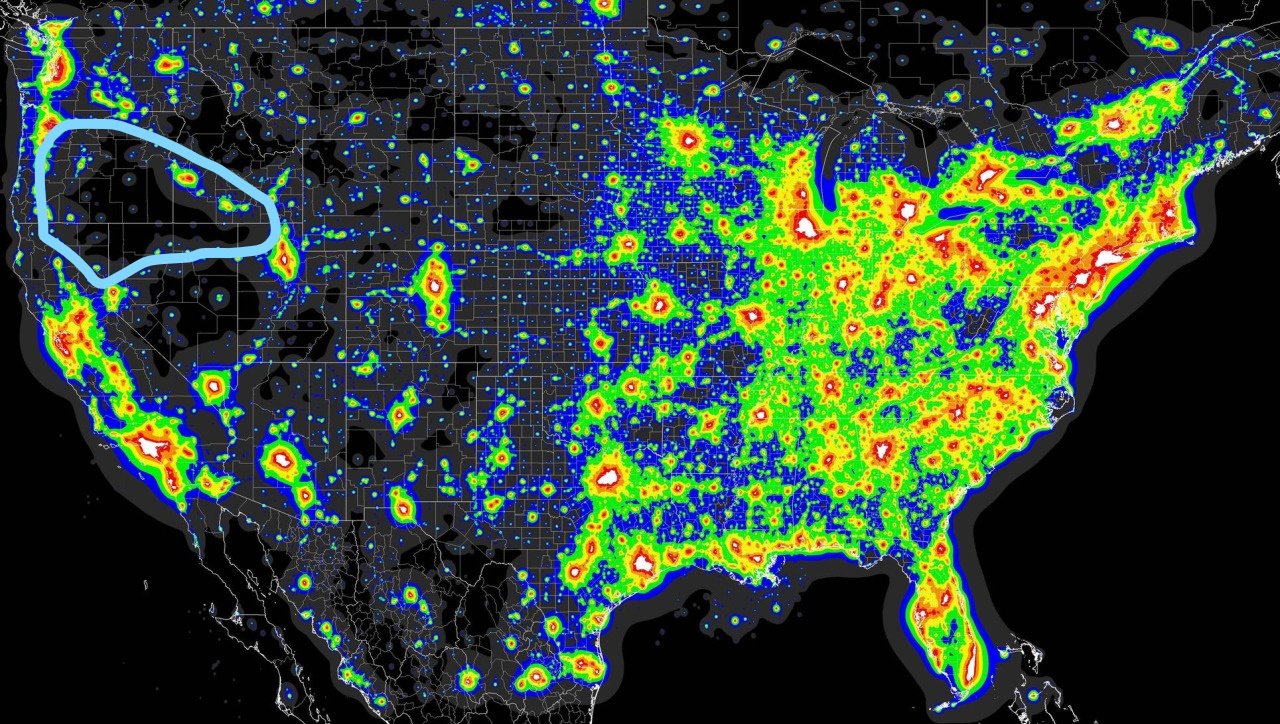

Read MoreFourth-fifths of Americans cannot experience (it’s more than just seeing) the Milky Way without a special trip to find a dark enough sky.

Read MoreWhile most Mountain Westerners favor the conservation of public lands, most of their elected officials are either openly hostile or passively wimpy. Conservation organizations need to rethink its nonprofit status to allow effective legislative and political engagement. Now.

Read MoreCongress told the Bureau of Land Management to remove a small, but fish-damaging, dam on the Donner und Blitzen Wild and Scenic River and the Steens Mountain Wilderness. The BLM may finally get around to it.

Read MoreIf President Biden wants to be remembered in history for saving the nation’s remaining mature and old-growth forests and trees for the benefit of this and future generations, the Forest Service is going to have to do significantly more than what it has proposed so far.

Read MoreIf you care about nature and the climate, you must not only vote but also give both time and money during the 2024 election, which is already far along.

Read MoreAlong with the great danger of the Oregon US House delegation becoming worse on public lands issues, there are also great opportunities for it to be better.

Read MoreThe prospective defeminization/emasculation of the Northwest Forest Plan by the Forest Service is likely inevitable. All the more reason for the Biden administration to promulgate an enduring administrative rule that conserves and restores mature and old-growth forests.

Read MoreThe world’s largest ecosystem management plan is under existential threat.

Read MoreMost Americans get their drinking, bathing, and flushing water from surface sources, most of which are unprotected from logging and other exploitation.

Read MoreThe future of the voluntary federal land grazing permit retirement option.

Read More