Even today, one can drive across the American West and view literally millions of acres of federal public lands under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) without even knowing it. In some rare cases, the BLM has erected a few road signs, but these signs don’t mean much to passersby because BLM public lands aren’t depicted on public maps—digital or paper—as are federal public lands administered by the Forest Service, the National Park Service, and the Fish and Wildlife Service.

Congress has also never afforded BLM public lands the same conservation status as other federal public lands. The Forest Service manages the National Forest System, the National Park Service the National Park System, and the Fish and Wildlife Service the National Wildlife Refuge System. All of these systems enjoy broad public support.

It’s time for the BLM to have its own comprehensive land conservation system: a National Desert and Grassland System. Congress should place appropriate BLM lands into a system of national deserts and national grasslands similar to the National Forest System. At the same time, Congress should, as suggested in last week’s Public Lands Blog post, abolish the BLM and replace it with a U.S. Desert and Grassland Service (USDGS). A USDGS would have a conservation mandate comparable to that of the National Forest System.

Integrating BLM lands into a new land conservation system would also increase public knowledge of and support for these federal public lands—which is important as a whining minority seeks to privatize federal public lands. I’m thankful that the Bundyites chose to occupy the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge rather than the nearby grazing allotment on BLM land that almost no one has ever heard of. The public understood that an armed occupation of their national wildlife refuge was wrong, but might not have been as concerned about occupying the adjacent grazing allotment on BLM land. It was this grazing allotment that was grazed by the convicted arsonists that first drew the attention of the Bundyians.

Actually, since 2009, ~32 million acres (13 percent of the ~247.3 million acres of BLM public lands) have been in the congressionally established National Landscape Conservation System (NLCS). However, most of the NLCS units are also units of the National Wilderness Preservation System, the Wild and Scenic Rivers System, or the National Trails System, or were otherwise specifically established by Congress for conservation. For the most part, the inclusion of lands in the NLCS affords no additional conservation status beyond what Congress had already extended.

As the name suggests, not all BLM public lands would go into the National Desert and Grassland System. BLM lands that are neither desert nor grassland would be transferred, as appropriate, to the National Park System, the National Forest System, or the National Wildlife Refuge System. On the other hand, the National Grasslands, now administered by the Forest Service as part of the National Forest System, should be transferred to the new National Desert and Grassland System.

By both elevating the “bureau” that manages the largest amount of federal public lands to a “service” and by placing those lands in a conservation “system,” BLM lands will not only be better managed for the benefit of this and future generations, they will be also be less vulnerable to loss to narrow private interests because the American public will know that these lands actually exist.

(I am deeply indebted to Mark Salvo, now Vice President for Landscape Conservation of Defenders of Wildlife, but then Director of the Sagebrush Sea Campaign and Counselor to the National Public Lands Grazing Campaign, who was co-author with me of a 2008 Larch Occasional Paper entitled Establishing a System of and a Service for U.S. Deserts and Grasslands.)

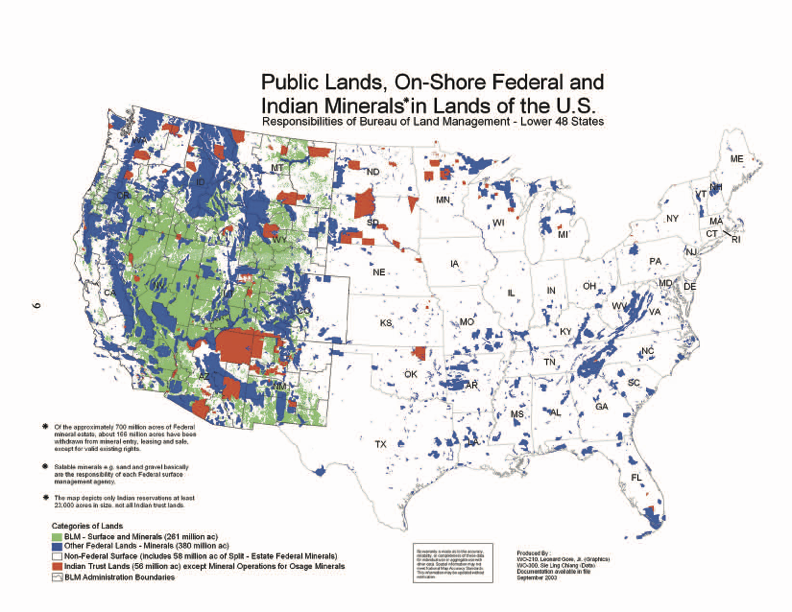

The blue lands are managed on the surface mostly by the Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, or the National Park Service as part of the National Forest System, the National Wildlife Refuge System, or the National Park System, respectively. Most of the green lands would become part of the National Desert and Grassland System. Not depicted are 58 million acres of “split estate” (nonfederal surface / federal subsurface) ownership (a total area approximately as large as the red areas).

The land surface shown in blue is primarily managed by the Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, or the National Park Service as part of the National Forest System, the National Wildlife Refuge System, or the National Park System, respectively. All of the green lands would become part of one of these existing conservation systems.