When I first registered to vote in 1973, there were sixteen Kerrs listed on Creswell City, Oregon, precinct roles, all related. Fifteen Republicans and one Democrat. One of those lovely old ladies who staffed the polling stations (when Oregonians actually went to the polls to vote) asked my father about this one Democrat named Andrew on her poll list. My father told me he answered her that he’d never heard of me.

Green Republicans Are Almost Extinct in Oregon

Though a Democrat, I did sometimes then support Republicans. Alas, the last time I voted for Republicans was in 1986 when Oregon secretary of state Norma Paulus was running for governor and Bob Packwood was seeking reelection to the U.S. Senate.

Paulus was running against Democrat Neil Goldschmidt and was far better on environmental issues than the former Portland major and U.S. secretary of transportation. Had it been known at the time that Goldschmidt was also a child-molesting rapist, Oregon would likely have had its first woman governor earlier than it did.

Packwood initially faced U.S. representative Jim Weaver, who later dropped out of the race before Labor Day. In 1986, I favored Packwood retaining his Senate seat and Weaver retaining his House seat, as the former was very, very good and the latter was simply great on wilderness, the issue of the era that separated the adults from the children in Oregon environmental politics—if not Oregon politics. I believed that Weaver couldn’t win statewide against Packwood, so it was a political calculation on my part. Packwood and Weaver are both the subjects of prememberances posted on this blog.

Paulus told me in the early 1990s she couldn’t win a Republican primary at that point. Social and religious conservatives were taking over the party, driving moderates to become independents or even (gasp!) Democrats. The Oregon Republican Party of Paulus, Packwood, Governor Tom McCall, and Senator Mark Hatfield was rapidly moving to the right, as was the national Republican Party.

From the late 1970s through the early 1990s, I closely followed environmental votes in the Oregon Legislative Assembly. Through the 1980s, many Republicans were environmental champions and, conversely, some Democrats were real earth-hating shitheads (it’s a political term of art). Close analysis of Oregon League of Conservation Voters (OLCV) scoring records indicated that as a party, Democrats were greener than Republicans, but there was much more overlap in greenness than there is today. A politician’s party did not automatically define positions on the environment as much as did the population density of her or his district (suburban Portland Republicans were much greener than rural Oregon Democrats).

I noticed that as downstate (not Portland) Democrats rose to the ranks of leadership in their legislative body, their OLCV biennial ratings tended to improve. It was just the opposite for downstate (there weren’t many in Portland, but a lot in the Portland suburbs) Republicans.

The OLCV recently released its 2017 scorecard on the last session of the Oregon legislature. The takeaway: Democrats everywhere are generally far greener than Republicans anywhere. (Most independents are so because they loathe both major parties, and minor parties in this country have the system rigged against them.)

The Era of Bipartisanship Has Passed

Many politicians call for a return to the era of bipartisanship as a solution to any woe. This call has resonance because the bipartisan era occurred in the living memory of baby boomers. But in the long arc of history this era did not last long, and the evidence of today does not give much hope of a return to it.

The Wilderness Act of 1964, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, and the Endangered Species Act of 1973—which were enacted into law with strong bipartisan majorities—could not pass Congress today. Not because conservationists wouldn’t have the votes, but because the bills would never get out of committee to get to the floor for a vote. A Republican majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate means that the various committees of jurisdiction for these bills are dominated by anti-environmental Republicans. (I take some solace that the same can be said of the Social Security Act of 1935, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The latter two became the law of the land with the votes of many Republicans, albeit in the minority in both houses, who joined with non-southern Democrats. Congress doesn’t really work like it used to or it should, but that’s a whole ‘nother blog post.)

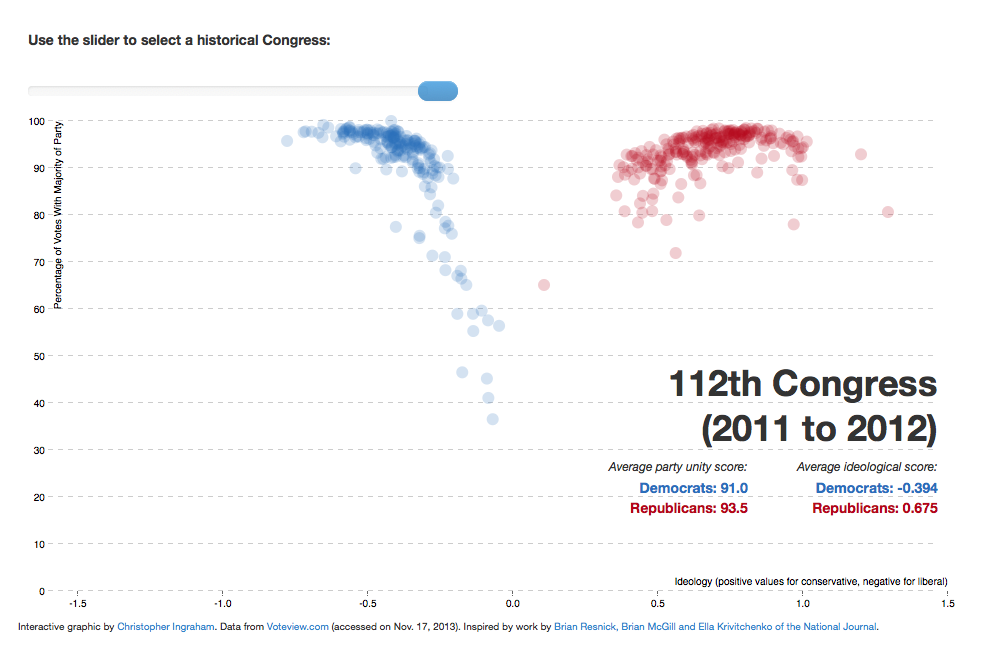

The Brookings Institution has a really cool slider graphic that I highly recommend you go play with. It goes back to the 35th Congress (1857–58) and shows that the era of conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans cohabiting in Congress started in the 1930s, peaked in the 1970s, and was dead by the dawn of the twenty-first century. Today’s 115th Congress (2017–18) is more starkly polarized ideologically than the 36th Congress (1859–60), which immediately preceded the Civil War. For comparison, Figures 1 and 2 juxtapose the Brookings snapshots of House of Representatives ideology and party unity of the 88th Congress (1963–64, the Congress that enacted the Wilderness Act) and the 112th Congress (2011–12, the most recent data depicted).

Figure 1. There was significant overlap of the ideologies of conservative Democrats and liberal Republicans in the 88th Congress, and the two parties were not as far apart ideologically as in the 112th Congress. Source: Brookings Institution.

Figure 2. There are neither liberal Republicans nor conservative Democrats in the 112th Congress, and the two parties are much farther apart ideologically than in the 88th Congress. Notice also that while both parties have moved to their respective poles, the shift of Republicans to the right is more pronounced than the shift of Democrats to the left. Source: Brookings Institution.

Another analysis, this one by the Pew Research Center, is similarly illustrative of liberals and conservatives realigning to be Democrats and Republicans respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3. When I first started voting in 1973, there were significant numbers of liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats. Today, both such political animals are extinct in Congress. Notice how Republicans are more conservative than Democrats are liberal. Source: Pew Research Center.

Wilderness Politics Is Extremely Partisan, but Wilderness Support Is Bipartisan

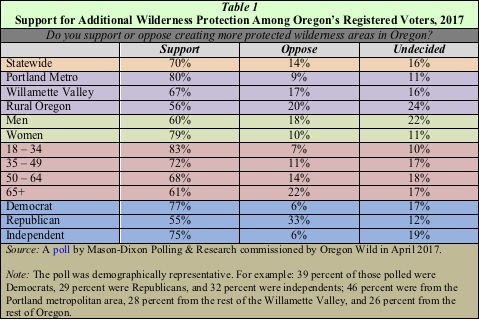

Keep in mind that in the 1960s, wilderness was a bipartisan issue not just because there were liberal Republicans but also because wilderness, a form of conservation, is a conservative issue. That’s actually still the case (Table 1), but the ideological purification of the two major political parties means generally that bills to establish more wilderness move forward when the Democrats are in power and go nowhere or even move backward when the Republicans are in power.

Even today, support of more wilderness protection is not an issue that separates on partisan (pronounced “ideological”) lines. While more than three of every four Democratic registered voters in Oregon support more wilderness protection, a strong majority of 55 percent of registered Republican voters also support more wilderness protection. On the wilderness issue, independent voters track very closely with Democrats (Table 1). The more urban, the more support for wilderness, but a majority of Oregon voters outside of the Willamette Valley also are in favor of additional wilderness protection.

Today’s Oregon Congressional Delegation Is Mostly Green

Oregon is a blue state and becoming darker blue politically. Table 2 shows the delegation’s conservation voting record. On the whole it’s an A- delegation. However, one Republican (F-) and one Democrat (C-) dramatically erode the delegation’s green score.

Kurt Schrader proudly touts his association with the New Democrat Coalition and the Blue Dog Coalition, meaning he brands himself as a conservative Democrat. His best vote for the environment is at the beginning of each Congress when he votes for a Democrat to be speaker. After that, it’s downhill in that his environmental voting record is rather dismal for an Oregon Democrat.

Greg Walden? Irredeemable.

Saving Public Lands for This and Future Generations Is Stalled for Now

Alas, the Republican Party of that great conservationist Theodore Roosevelt is dead.

With Republicans controlling both houses of Congress and the White House, I don’t see a political path for the conservation of public lands for this and future generations, unless as part of a grand bargain that sacrifices other public lands and/or other popular American values.

If the Democrats obtain a majority in either house of Congress, public lands conservation bills could again start to move. If a Democrat again lives in the White House, liberal use of the conservative (pronounced “conservation”) National Monuments Act of 1906 could recommence.