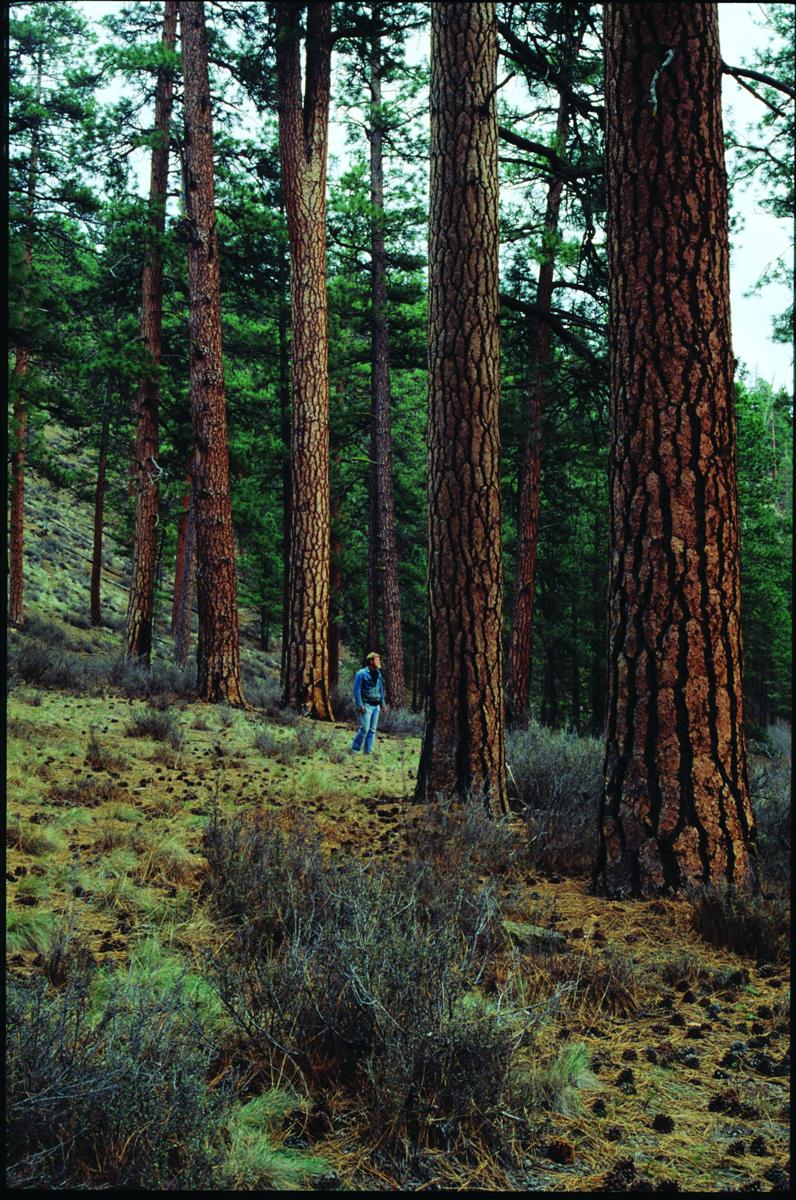

Old-growth ponderosa pine in the proposed Metolius Breaks Wilderness. Image: Elizabeth Feryl

Limitations on party size, pack animals, camping sites, and campfires have long been in effect to minimize human impacts on delicate environments in wilderness areas. However, the Forest Service increasingly realizes that protecting the natural character of vegetation and soil alone will not adequately protect wilderness values. The agency now considers limiting the actual number of visitors to protect another legally mandated wilderness value: solitude. If too many people are in the woods at once, even no-trace camping will not provide adequate protection for wilderness.

Limits have been considered on visitors to Oregon’s Mount Hood Wilderness and Washington’s Alpine Lakes Wilderness, which are within easy reach of the Portland and Puget Sound metropolitan areas. In some cases, the Forest Service has contemplated visitor reductions as large as 60 and 90 percent. Such limits are already common on popular floating rivers including the Rogue and the Colorado.

Choosing to shoot the messenger rather than solve the problem, former Senator Slade Gorton (R-WA) promoted legislation that would have prevented the Forest Service from imposing limitations on wilderness visitation. A better solution is for Congress to simply add more areas to the National Wilderness Preservation System. In a nation and a world with an expanding population, the supply of protected wilderness has not kept up with the demand.

The National Forest System and the Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) forested holdings contain many de facto wilderness areas that are worthy of congressional wilderness protection. These lands already provide significant backcountry recreation opportunities and could absorb additional visitors in the future, if they are not roaded and clear-cut. However, if these roadless forestlands are degraded, recreationists will be displaced. This will funnel even more visitors into existing protected wilderness areas, threatening their natural character.

In Oregon, the majority of the lands protected as wilderness are either high-elevation forests or “rock and ice” above timberline. Though small areas of low-elevation old-growth forest have also been protected as wilderness, much more could be if Congress would act soon.

While the National Park System and the National Wildlife Refuge System also have lands that qualify for wilderness designation, the biggest potential sources of new wilderness areas in the Pacific Northwest are the federal forests (managed by the Forest Service and the BLM) and the BLM’s desert holdings.

Compared to its four adjacent neighbors, Oregon has the smallest percentage of its lands designated as units of the National Wilderness Preservation System. While the average of the areas of the five states protected as wilderness is more than 9 percent, in Oregon less than 4 percent of the land is so protected. Oregon has 47 wilderness areas totaling 2,457,473 acres. Additional potential wilderness areas (a.k.a. roadless areas) in Oregon total more than 12 million acres, with approximately 61 percent of that area being generally tree-free (in the Oregon High Desert and other desert areas considered part of the sagebrush steppe, aka Sagebrush Sea) and the remainder generally forested. Congress should expeditiously expand the National Wilderness System in Oregon.

“We dare not let the last wilderness on earth go by our own hand, and hope that technology will somehow get us a new wilderness on some remote planet, or that somehow we can save little samples of genes in bottles or on ice, isolated and manageable, or reduce the great vistas to long-lasting video-tape, destroying the originals to sustain the balance of trade and egos.”

For more, see Larch Occasional Paper #11, entitled The National Wilderness Preservation System in Oregon: Making It Bigger and Better.

[A version of this piece first appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness, by the author (Timber Press 2004).]