It is safe to say that most conservationists, not to mention the rest of Americans, have never heard of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS). It is a federal and state partnership that is little known and therefore underappreciated.

A great blue heron in the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve in Maine. Source: NOAA.

The NERRS was established by Congress as part of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 and is a partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and “coastal” (including Great Lakes) states. NOAA has promulgated regulations to administer the system.

The 2017 Funding Summary for NERRS indicates that NOAA contributed more than $23 million to implement the NERRS program. State and university partners contributed $6.6 million.

Why Estuaries?

Why not?

Most, but not all, estuaries are regions where “rivers [and streams] meet the sea and fresh-flowing river water mingles with tidal salt water to become brackish, or partly salty.” There are also freshwater estuaries, where stream water and water in very large lakes meet. Freshwater estuaries are similarly affected by tides, storms, and different water chemistries.

NOAA informs us of multiple estuarine benefits:

· Estuaries act like huge sponges, buffering and protecting upland areas from crashing waves and storms and preventing soil erosion. They soak up excess water from floods and stormy tidal surges driven into shore from strong winds.

· Estuaries provide a safe haven and protective nursery for small fish, shellfish, migrating birds, and coastal shore animals. In the U.S., estuaries are nurseries to more than 75 percent of all fish and shellfish harvested.

· People enjoy living near estuaries and the surrounding coastline. They sail, fish, hike, swim, and enjoy bird-watching. An estuary is often the center of a coastal community.

The National Estuarine Research Reserve System (the new He’eia NERR in Hawaií is not shown). Source: Wikipedia

NERRS Today

There are presently twenty-nine National Estuarine Research Reserves (NERRs) totaling 1,339,027 acres located in twenty-three states and one territory (see Table 1). Oregon’s NERR is South Slough (of the Coos Bay estuary), located five miles south of Charleston. Each reserve has a management plan and site profile to guide research and management.

South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, part of Coos Bay near Charleston, Oregon. Source: NOAA

The research reserves are focused on the following:

· Stewardship. Each site undertakes the initiatives needed to keep the estuary healthy.

· Research. Reserve-based research and monitoring data are used to aid conservation and management efforts on local and national levels.

· Training. Local and state officials are better equipped to introduce local data into the decision-making process as a result of reserve training efforts.

· Education. Thousands of children and adults are served through hands-on laboratory and field-based experiences. School curriculums are provided online.

A research reserve is established in a six-step process that begins with an expression of interest by a state. Once NOAA returns the interest, the process moves to site selection and formal nomination. A draft management plan and draft environmental impact statement are followed by final versions of the two. Then the NOAA administrator approves the designation findings and a memorandum of understanding between NOAA and the state makes it all official. The final step is a designation ceremony, which ideally involves celebratory activities. It takes an average of four to six years, but as little as three years and as long as thirteen, to complete the process.

The Delaware National Estuarine Research Reserve in Delaware. Source: NOAA

The Future of NERRS

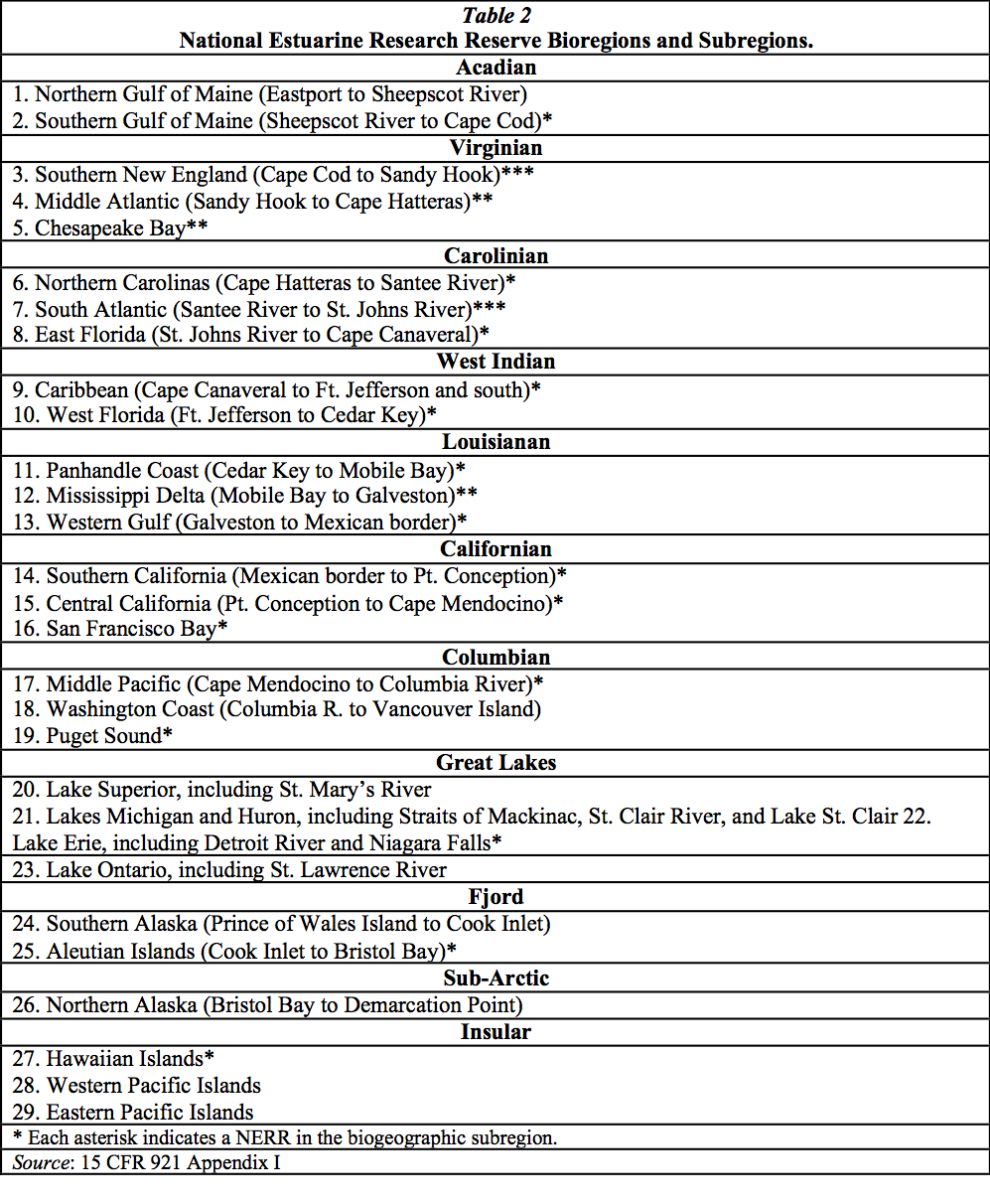

NOAA’s first priority for new estuarine research reserves is that they represent biogeographic subregions and estuary types not already represented in NERRS. There are eleven major bioregions with twenty-nine subregions along the coasts of the United States. Twenty subregions are currently represented in NERRS (Table 2).

It’s probably not the best time to be doing it, the federal administration being what it is, but NERRS needs to be rounded out so that every one of the twenty-nine biogeographic subregions is represented in the system. To aid in research that compares and contrasts, it would be best if there were at least two, if not more, estuarine research reserves for each subregion.

At some point NERRS will be adequate for its purpose—research. While the research reserves are protected to further estuarine research, most or parts of all estuaries are not adequately protected for conservation purposes for the benefit of this and future generations. There needs to be a National Estuary Protection System to conserve and restore the best of the nation’s estuaries, comparable to the National Wilderness Preservation System, the Wild and Scenic Rivers System, the National Wildlife Refuge System, the National Park System, and the like. Until there is a National Estuary Protection System, more estuary lands should be designated as wilderness, wild and scenic rivers, parks, refuges, and/or national monuments.

The Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve in California. Source: NOAA.