This is the second part of a two-part examination of what “rural” really means in Oregon and how statistically insignificant (and in all likelihood to become more so) the rural population is today. In Part 1 we examined how much of Oregon is truly rural. In Part 2 we examine the current and future power dynamic between rural and urban Oregon.

Figure 1. The Flora Methodist Church as built in 1896. Flora is located in northern Wallowa County at 4,350-feet elevation. It was platted in 1897 and by 1910 had 200 residents. In 1918, an eight-room school was built. The Post Office operated from 1890 to 1966. A ghost town, Flora is considered “the most substantial town to fail” in Northeast Oregon. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives (image) and Wikipedia (text)

As Part 1 of this piece pointed out, a dominant narrative of the rural-urban divide in Oregon often frames our politics, including that of public land management. Oregon’s public lands make up approximately three-fifths of the state. Some counties consist mostly of federal and state public land, while others have very little. As established in Part 1, the truly rural counties in Oregon (ten out of thirty-six) contain just 2.5 percent of the state’s population. These counties are generally those that contain larger swathes of public land.

Many locals in rural (less-populated) areas think they should have more of a say about public lands in their area than those who live farther away. Such is a fundamental tension between X and Y (fill in your bifurcation of choice here: urban v. rural, upstate v. downstate, “Portland” [includes suburbs] v. the rest of Oregon, the Willamette Valley v. the rest of Oregon, or other). But they come up against the constitutional principle of one-person-one-vote. While the principle does not favor geography, there are simply more urban voters. Alas for rural citizens, the tilt toward urban centers of power is only going to grow more pronounced as population change occurs in the years ahead.

What’s Fair?

In response to the recent Public Lands Blogpost entitled “A Sixth Congressional District for Oregon?” a regular reader wrote:

What an interesting analysis of Oregon’s Congressional Districts! My main concern is that the rural eastern part of Oregon gets a fair shot at legislative decisions. I don’t care what party controls it, just be fair for rural people. So many of the urbanites I encounter seem to care less for anybody living in the country. I’ve got a neighbor in Springfield who feels rural people are stupid. He is actually the stupid one. Thanks for sharing your detailed analysis!

(Okay, I could have left off the first and last lines for the matter I’m going to address, but who better than I to toot my own horn?) The reader seeks fairness for the “rural eastern part of Oregon.”

We first must agree upon what “fairness” means. Is it that rural eastern Oregonians should be heard before decisions affecting them—either proportionately or disproportionately—are made by the larger body politic? Or is it that the majority of rural eastern Oregonians should get their way even when this goes against the wishes of the majority? If fairness means the former, this should equally apply to all affected groups, be they rural or urban. It’s only fair. If fairness means the latter, this is not possible in our constitutionally mandated one-person-one-vote democracy and really just amounts to favoring a class.

Many of those who live near or off of public lands (mostly logging, grazing, and mining) think they should have a greater say in how state and federal public lands are managed than those who live farther away. Alas, even some Oregonians and Americans who don’t live near, let alone off of, public lands agree. I do not.

State public lands belong to all Oregonians, and federal public lands belong to all Americans, regardless of where they live or even have yet to live. Public lands are a common legacy and treasure that belong to all. The public land asset is no more owned and should not be more controlled by those who are closer in proximity. Imagine if locals wanted to put a casino on the federal public land that is the National Mall in Washington DC. After all, both would create jobs, and those closest to the resource know best how to manage it (sarcasm alert!).

One-Person-One-Vote: A Fair Principle That Favors Urban Over Rural Voters

During the Sagebrush Rebellion (ca. 1980), aggrieved mostly white and mostly male and rural westerners organized around the belief that the states were the ultimate sovereign and outranked the United States in authority—that is, if the United States government was legitimate at all. In the current incarnation of the rebellion, typified by the ravings of the Bundy Band, it is not the state that is sovereign so much as the county. This is because, statistically, if one lives in the American West, one most likely lives in a nonrural setting.

Poor Cliven Bundy lives in Clark County, Nevada, which, due to greater (or not so great) Las Vegas, is one of the most urbanized counties in America, even though his particular census tract is large in size and small in population. Alas for Cliven—both the states and the United States are sovereign, and all those Nevada voters, mainly in Vegas and up there in Reno–Carson City, ain’t rural.

The fact is that counties are mere administrative subdivisions created for the convenience of the sovereign state. They are convenient for measuring population and demographics and for providing some government services. Average Portlanders think most about Multnomah County as a government when getting a marriage or dog license or when summoned for jury duty, and almost never think of Multnomah County as the place they live. In rural areas, counties take on a greater importance for the delivery of government services and geographic identity than in urban areas.

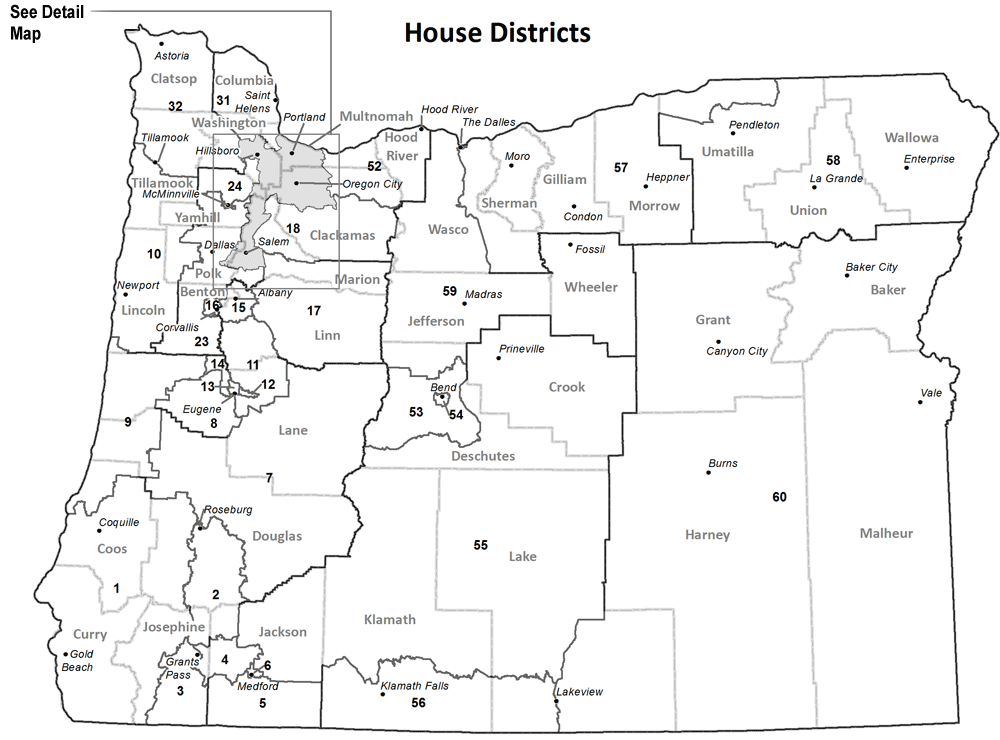

To the consternation of many in rural Oregon, counties do not confer greater voting power regarding public lands issues on residents merely by virtue of living there. One-person-one-vote means that a voter in Wheeler County (the City of Fossil and environs) has just as much political power as a voter in Washington County (greater Beaverton), and no more or less. The problem for Fossilites is that their numbers don’t equate in relative or absolute terms to much political power (Map 1). With one-person-one-vote, political power accumulates in urban areas, because people accumulate in urban areas.

Map 1. Oregon House of Representative districts. When the districts were drawn after the 2010 census, each had 1/60th of the state's population. Notice the gray mass in the lower Willamette Valley, which means there are so many districts they cannot be mapped at a statewide scale. Source: Oregon Secretary of State

While Oregon has thirty-six counties evenly spaced on both sides of the Cascade Crest, that’s where the balance ends. Multnomah County has ~540 times greater population than Wheeler County, and that number continues to rise. Harney County is ~23 times larger in land area than Multnomah County, but there are ~2,619 times more people per square mile in Multnomah County than Harney County. Most (though not all) of Portland is in Multnomah County. This is why greater Portland (increasingly pronounced “Portlandia”) looms large in all things Oregon politics.

The Reality of Population Change in Oregon

The populations of Oregon’s counties are changing dramatically. Bill Clinton once noted that “everybody is for change in general, but they are scared of it in particular.” While I generally loathe population growth anywhere, many do not (especially if they are a unit of it), and most people fear population decline (especially if it is where they live). This is another fundamental tension between X and Y (fill in your bifurcation of choice here).

In general, Oregon’s truly rural counties are losing population while the rest are gaining population. Between 1980 and 2016, eleven counties grew more rapidly and eighteen counties grew more slowly than the state as a whole, while seven counties lost population (Table 1)

Table 1. Population Change of Oregon Counties, 1980–2016. Source: Oregon Blue Book

Let us zoom in on a case in point. From 1996 to 2000 I lived in very noncore and 100-percent-rural Wallowa County (Figures 1 & 2). Many of the old buildings in the county seat of Enterprise have two floors, but in most cases the second floor are underutilized, even if the first is occupied by a business, as the space isn't needed. Wallowa County once had significantly larger populations (Table 2). The decennial census population peaked in 1920, but the true population peak was probably in 1917, just before many local lads went off to fight the Kaiser in World War I or to cities to get war-related jobs.

Table 2. Historical Population of Wallowa County, Oregon. Source: Wikipedia

When I lived in Wallowa County, the old guard (who generally hated me for what I represented) was aging. When asked about their kids, they had to admit that almost all had gone off to the cities. The same for their siblings, and the same for their aunts and uncles. More subscribers than not to the Wallowa County Chieftain, the weekly paper of record, are snowbirds who winter elsewhere.

Despite this multi-generational exodus of “locals”, the social, economic, and (eventually) political gene pool of Wallowa County is diversifying with recent residents generally supplanting longer residents who have left. The population has been and is projected to continue to be relatively stable (some would say “stagnant”; I would not). Evidence of this diversity is found in US Department of Agriculture data about “creative class” counties—those with disproportionately high numbers of “engineers, architects, artists, and people in other creative occupations.” Oregon has eleven creative-class counties (Map 2), and Wallowa is among them. Other nonmetro counties in the creative class are Lincoln and Lake, while metro counties include the usual suspects: Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas, Polk, Benton, Lane, Jackson, and Deschutes. Nonmetro doesn’t have to mean low-skilled.

Map 2. US Department of Agriculture–defined creative-class counties. Source: USDA

For what it’s worth, the Portland State University Population Center forecasted in 2016 that Wallowa County would have a population of 7,013 in 2066. (I don’t even want to think what Oregon’s population will be in 2066, but it will be unlikely to include me.) In addition, the population is forecasted to be on average much older. Most likely, the populations of rural counties will continue to be outpaced by the populations of most other counties and Oregon on average.

Further Whither “Rural” Oregon?

Advances in education, automation, transportation, and communication, along with excesses in population, are tending to make the rural more urbane. It’s been that way since the beginning of the First Industrial Revolution, and the trend will continue as society stumbles into the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In addition, the pull of the city is causing a situation of social selection, if not genetic selection, in which those left in rural areas with significantly declining populations are the least capable of embracing change. Nonetheless, change is coming—at breakneck speed.

It won’t work, and is rather patronizing besides, to make rural people a protected class in our politics. One-person-one-vote is a cherished, rational, just, and fair principle.

Figure 2. In 1915, an eight-room school was built in Flora, Oregon. Restored, it is known as the Flora School Education Center, featuring the pioneer arts. Source: Wikipedia