In “After Yarnell: Why America’s Fire-Industrial Complex Can’t Be Stopped,” subtitled “We’re wasting billions on a fight we can’t win” (Outsidemagazine, June 30, 2014), Grayson Schaffer wrote:

Whatʼs needed isnʼt better technology or communication, but the final recognition that weʼre no better at dousing forest fires than we are at stopping tornadoes or hurricanes. We shouldnʼt be fighting them in the first place. As with other natural disasters, we should urge individual and community preparedness, organize evacuations, and provide relief in the aftermath. The only problem with fire is the persistent, juvenile belief that we can fight it in hand-to-hand combat and win. We canʼt. There may have been a time, before long-term drought and years of fuel buildup, when total suppression was possible. But it’s a foolhardy strategy now.

Total suppression was neverpossible. Large wildfires have always ended either because they ran out of fuel or, most often, because the weather changed. (How many times have I read a newspaper quote from a fire boss or the fire’s public relations flack to the effect: “We had the fire under control, but then the weather changed.” If a change in temperature, humidity, and/or wind conditions caused one to lose “control” of the fire, one never was in control.) As for small wildfires, most go out on their own. If firefighters happen to get there soon enough, they can pretend they made a significant difference. However, wildland fire suppressed is merely wildland fire delayed.

Actually, Grayson, I appreciate your rhetorical sop to mollify the people and institutions that want to change minds and behavior. It is easier to persuade people to conclude what they have been doing is no longer a good idea rather than what they have long done was never a good idea.

Wildfire suppression is a losing strategy that costs taxpayers lots of money, especially since Congress isn’t providing critical oversight of the Forest Service’s firefighting budget. What’s needed is a federal wildfire policy that’s based in science. Fortunately, there is Tania Schoennagel, PhD, a wildfire scientist at the University of Colorado–Boulder whose research “addresses the causes and consequences of western forest disturbances.” Her peer-reviewed science, based on actual evidence, is speaking truth to power—to the fire-industrial complex (private industry, bureaucratic entities, and legislative funders), which sees logging and firefighting as the only tools to fix wrongly identified problems.

Figure 2. The fire-industrial complex needs to be redirected to only set fires on wildlands and only put out fires on buildings. Source: National Park Service.

The Soberanes Fire: The Perils of a Blank Check

While the Soberanes Fire in 2016 in and near the Los Padres National Forest in southern California has been the most expensive wildfire to date, just wait. The Forest Service has a blank check from Congress for fighting fire. No fire boss has ever been sanctioned or disciplined for spending too much money. Here’s the executive summary from Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology on the Soberanes Fire:

The Forest Service spent a record $262 million fighting the Soberanes Fire, spending several million dollars each day over the course of that three-month long fire which mostly burned in the Ventana Wilderness Area.

Forest Service wildfire suppression spending lacks fiscal restraint and accountability, and Congress is failing to provide critical oversight of the agency’s firefighting budget. An inflated firefighting budget in the Forest Service’s FY2016 appropriations gave the agency the ability and perceived necessity to spend the extra money on the Soberanes.

Use of “heavy metal” suppression resources—specifically large airtankers and dozers—were major cost drivers but they had very limited success in stopping fire spread.

Significant amounts of retardant and dozerlines were used as indirect or contingency firelines located far away from the wildfire’s perimeter, and never engaged the wildfire. These added extra risks to firefighters, costs to taxpayers, and impacts to the land.

Fire managers failed to update their risk assessments of the costs and benefits of selected suppression strategy and tactics as the location and conditions of the Soberanes Fire changed over its three month duration. Aggressive firefighting actions continued long after the wildfire had moved away from communities or infrastructure, and the threat to structures had ceased.

Suppression actions inside and adjacent to the Ventana Wilderness Area were inappropriate, excessive, and ineffective—causing significant and lasting damage to wilderness values.

Federal fire managers must shift priorities from fighting fires in fire-adapted ecosystems in backcountry wildlands to protecting fire-vulnerable homes and communities.

With Congress debating the Fiscal Year 2019 Omnibus Spending Bill at the time this report was issued, the Soberanes Fire Suppression Siege offers a cautionary tale prompting Congress to demand fiscal restraint and accountability for Forest Service suppression spending.

Stellar Wildfire Science

Some superb academics have moved and are moving the needle in matters of federal public lands policy. Forest scientist Jerry Franklin and forestry professor Norm Johnson have effectively rewritten federal forest management policy, as have Jim Sedell and Gordon Reeves for federal forest stream management policy, as did Jack Ward Thomas for federal forest wildlife policy. Tania Schoennagel is doing the same for federal wildfire policy. Tania’s challenge is that, relatively speaking, she’s just begun. I also would argue that reforming the fire-industrial complex is even harder than reforming the logging-industrial complex.

What follows is my distillation of Schoennagel’s 2018 presentation to the American Geosciences Institute, entitled “Adapting Wildfire Management to 21st Century Conditions.” You can watch the webinar video or look at her slide deck. I have included most of her slides here with my own captions, which are, I hope, informative, elaborative, and/or provocative.

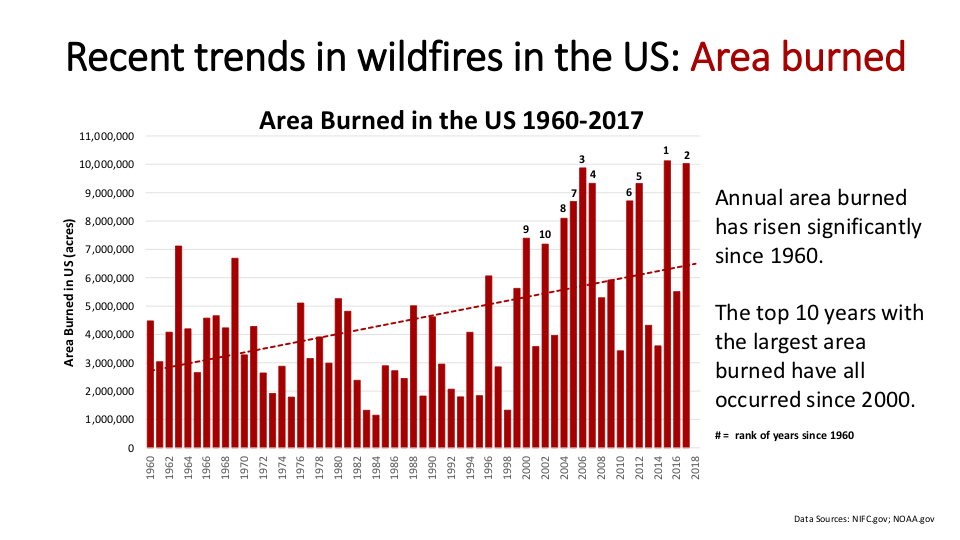

Figure 3. From 1960 forward, the ten largest burns have occurred since 2000. Yes, there have been relatively small burn years during that time, but notice that recently the area burned in small burn years is generally comparable to the area burned in average burn years in the earlier decades.

Figure 4. The correlation with global warming is strong enough, and when considering other evidence, to conclude causation.

Figure 5. If you don’t like wildfire, there’s always Illinois, Vermont, New Hampshire, or Rhode Island.

Figure 6. While more area is burning, the severity of the burning has not increased, despite what you may hear on the news. Crime rates are not rising either, but you wouldn’t know it watching the evening news.

Figure 7. Human-related ignition, not lightning, is the cause of most wildfires. Also, humans are careless the entire year, while lightning strikes spike in peak summer. The northern Oregon Coast Range in dark red has the lowest incidence of lightning strikes in the United States, while the eastern United States in dark red has some of the highest levels.

Figure 8. It’s worth examining the lightning-versus-human-caused wildfire ratio a bit more, so here’s a non-Schoennagel slide showing that while the American West is bearing the brunt of most wildfires, one cannot blame lightning for most of them. Source: Vaisala.

Figure 9. The Forest Service would have us believe that all forests in the American West are tinderboxes set to explode. However, the narrative that fire suppression has caused “overgrown” forests is true primarily in open ponderosa pine–dominated forests. Most forests in the American West are not such forests. Logging out the largest, most fire-resistant (and most profitable) trees has exacerbated the situation, as has the widespread grazing of domestic livestock. Finally, the most flammable “forest” of all is an industrial monoculture plantation of Douglas-fir.

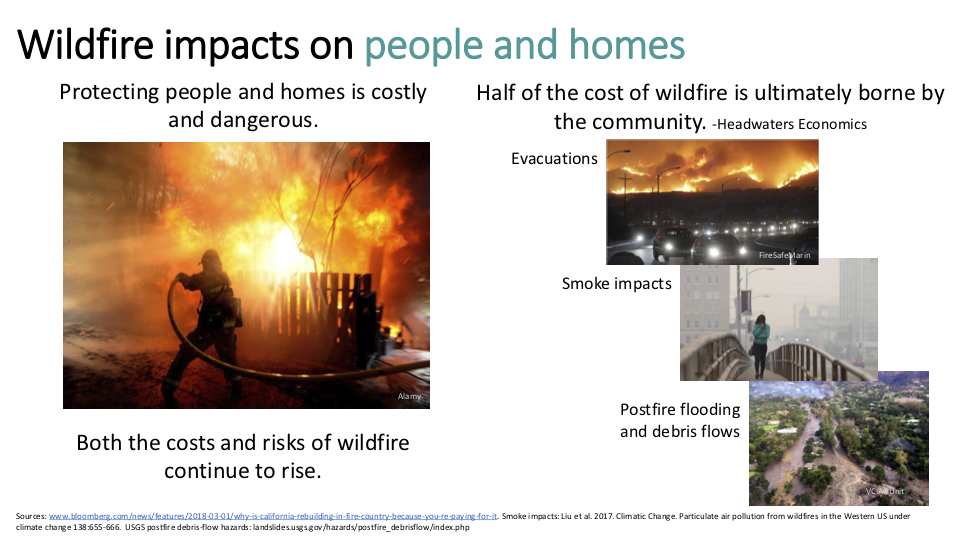

Figure 10. It’s the WUI, stupid. The wildland-urban interface is where buildings infest the wild and is growing in both area and density. Local governments fail to regulate or prohibit citizens from foolishly building in the WUI because Uncle Sugar will pick up most of the tab and the foolish citizens won’t take it out on their local officials in the next election.

Figure 11. The federal government picks up much of the wildlands firefighting tab in the American West, either directly or through grants to local governments.

Figure 12. If you think it’s bad now, just wait, especially if humans continue to dither on addressing the climate emergency.

Figure 13. While Congress recently revised how taxpayers will pay for the bloated Forest Service firefighting budget, it has continued to give the Forest Service a blank check. Those chemical fire-suppressant bomber runs are more telegenic (often timed to be shown live on the evening news) than effective—and are harmful to fish, wildlife, and humans.

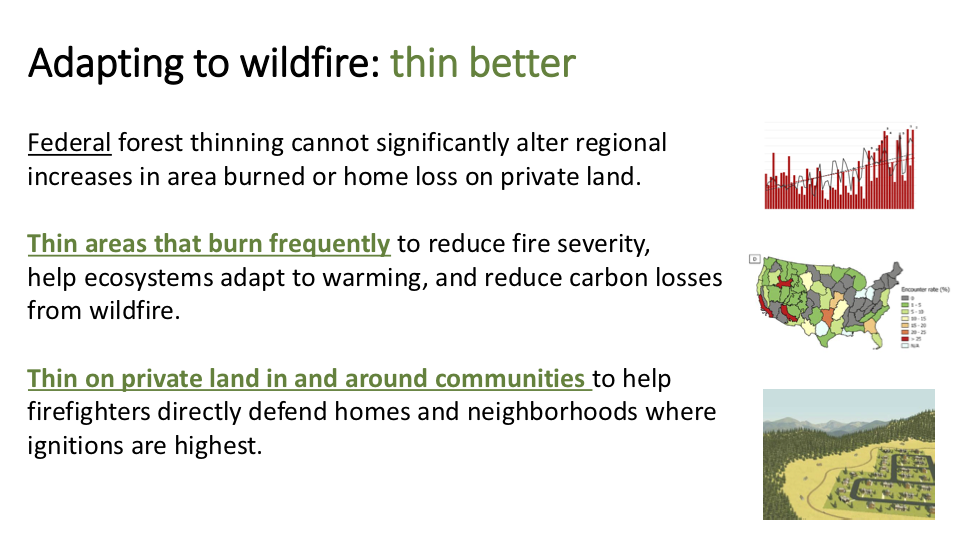

Figure 14. For all the money spent “thinning” the forest to reduce the risk or intensity of wildfire, on average such thinned areas encounter a wildfire about 1 percent of the time.Want to improve the odds? To get “thinning” (commonly pronounced “logging”) to have a one-in-three chance of encountering a fire, first double the budget. Then double it again. Again with the doubling. Then another doubling. Now double it one more time. Not only does this require a thirty-two-fold increase in the budget (something Congress is not likely to do), it’s enough to clear-cut every acre of federal forest once and for all.

Figure 15. I would also add: think better, spend better, and elect better.

Figure 16. Similar spending on preventive health care yields comparable returns, yet we don’t do it.

Figure 17. The federal government should condition any grants to local governments on local governments actually stepping up.

Figure 18. Economists have a term (but need a better one) for this: moral hazard(“lack of incentive to guard against risk when one is protected from its consequences”).

Figure 19. Most of the WUI is not on federal land, and most of the WUI is not forested.

Figure 20. Hallelujah and amen!

Tania, it’s time to write a book. I’m thinking Island Press. Then the documentary (perhaps as several YouTube videos).

For More Information

Articles, Opinion Pieces, and Reports

Bevington, Douglas. 2019. A New Direction for California Wildfire Policy—Working from the Home Outward. Leonardo DiCaprio Foundation.

Ingalsbee, Timothy. 2017. Whither the paradigm shift? Large wildland fires and the wildfire paradox offer opportunities for a new paradigm of ecological fire management. International Journal of Wildland Fire26: 557-561.

Ingalsbee, Timothy, et al. 2018. The Sky’s the Limit: The Soberanes Fire Suppression Siege of 2016. Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology.

Schoennagel, Tania, et al. 2017. Adapt to more wildfire in western North American forests as climate changes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences114: 4582–4590.

Books or Book Chapters

Kerr, Andy. 2006. “The Ultimate Firefight: Changing Hearts and Minds” in Wildfire: A Century of Failed Forest Policy, ed. George Wuerthner (Washington, DC: Island Press).

Ingalsbee, Timothy, and Urooj Raja. 2015. “The Rising Costs of Wildfire Suppression and the Case for Ecological Fire Use” in The Ecological Importance of Mixed-Severity Fires: Nature’s Phoenix, ed. D. DellaSala and C. Hanson (Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Academic Press).

Wuerthner, George (ed.). 2006. Wildfire: A Century of Failed Forest Policy(Washington, DC: Island Press).

Websites

Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics, and Ecology “promotes safe, ethical, and ecological wildland fire management” and strives “to inform and empower fire management workers and their citizen supporters to become torchbearers for a new paradigm in fire management.”

Headwaters Economics works on, among other things, reforming federal wildfire policies.