This is the second of four Public Lands Blog posts that examine the topic of national parks in Oregon. Part 1 explored Oregon’s one success in establishing a national park. Part 2 discusses multiple failures to establish additional national parks in the state. Part 3 will examine both successful and failed attempts to expand Crater Lake National Park. Part 4 will look at the potential supply and demand for additional national parks in Oregon and the political challenges and chances.

Figure 1. The Three Sisters in Oregon’s central Cascade Range (left to right: South, Middle, North). Early settlers called them Charity, Hope, and Faith, respectively. They were proposed to be part of a Volcanic Cascades National Park from the Columbia River Gorge to Crater Lake National Park. Source: Wikipedia (Lyn Topinka, US Geological Survey).

“The parks do not belong to one state or to one section. . . . The Yosemite, the Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon are national properties in which every citizen has a vested interest; they belong as much to the man of Massachusetts, of Michigan, of Florida, as they do to the people of California, of Wyoming, and of Arizona.

Who will gainsay that the parks contain the highest potentialities of national pride, national contentment, and national health? A visit inspires love of country; begets contentment; engenders pride of possession; contains the antidote for national restlessness. . . . He is a better citizen with a keener appreciation of the privilege of living here who has toured the national parks.

—Stephen T. Mather, director of the National Park Service 1917–1929

For more than a century, the federal government has considered and Oregonians have proposed, debated, and killed national parks in Oregon other than Crater Lake National Park.

Oh, what might have been!

• Mount Hood National Park

• Hells Canyon National Park

• Oregon Coast National Park

• Oregon Dunes National Seashore

• Steens Mountain National Park

• Owyhee Canyonlands National Park

• Volcanic Cascades National Park

In a 2016 article in the Oregonian entitled “3 National Parks in Oregon That Never Happened,” Jamie Hale wrote:

But in the mid-20th century, Oregon’s scenic beauty was prized by the park service, which proposed several sprawling national parks around the state. An April 28, 1940 Oregonian article summed it up simply, if not dramatically: “So far as the national park controversy is concerned, Oregon, like ancient Gaul, is divided into three parts.”

Three stunning spots in scenic Oregon were front-runners to land the national park status, a designation that was so divisive at the time that the Oregonian ran a three-week series in 1940 on the northwest “park problem.”

Hale noted the failed efforts to establish three national parks: Mount Hood, Hells Canyon, and Oregon Coast. I add to his list four more: Oregon Dunes, Steens Mountain, Owyhee Canyonlands, and Volcanic Cascades.

Mount Hood

Figure 2. Mount Hood, Oregon’s highest point. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon Archives

My previous Public Lands Blog post entitled “Conserving and Restoring the Mount Hood National Forest” told the story of the failed attempts to achieve a Mount Hood National Park.

Hells Canyon

Figure 3. Hells Canyon, a landscape so grand that it’s impossible to capture in one photograph. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon Archives.

Oregon shares Hells Canyon with Idaho. Hells Canyon is grander than the Grand Canyon, as it is both narrower and deeper (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Hell yes, Hells Canyon is grander than the Grand Canyon. Source: Forest Service.

Hale writes:

The deepest river gorge in North America, located on the northeast border of Oregon and Idaho, was like a natural choice for a national park—of course, that sentiment wasn’t universal. Already managed by the U.S. Forest Service, locals weren’t thrilled about the notion of switching the land over to a park.

“The proposal to make Hells canyon a national park runs head on, like a locomotive collision, into the economics of Wallowa County,” the Oregonian reported in 1940. “Each year the forest service puts into the Wallowa county treasury an average of $10,636 as its share from grazing and timber fees. . . . A national park pays neither taxes nor these fees.”

The proposed park at Hells Canyon was a perfect mirror for the dilemma that has always surrounded—and continues to surround—the establishment of public lands: Is setting aside the land for scenic enjoyment worth locking up its commercial value?

That question lingered for decades, but was finally answered at Hells Canyon in November, 1975, when the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation establishing the Hells Canyon National Scenic Area—a designation that came with new conservation status and continued management by the Forest Service.

(Southern) Oregon Coast

Figure 5. A small state park at Cape Sebastian is a fragment of what could have been the Oregon Coast National Park. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon Archives.

An Oregon Coast National Park was proposed in Curry County, but most of the proposed park acreage was either in private ownership or was federal land administered by the Bureau of Land Management. Hale writes:

When Olympic National Park claimed a chunk of the Washington coastline, it stirred the imagination of the park’s neighbors to the south: What about a national park on the Oregon coast?

“A park on the Oregon coast would be unique among all the national parks of the region,” the Oregonian reported, encompassing 30,000 acres of land in southwest Curry County, stretching 21 miles along the coast from Gold Beach south to Brookings.

But while national park designations brought up controversy across the country, chances looked good for the Oregon Coast, the Oregonian reported in a July 14, 1940 feature. Oregon Sen. Charles L. McNary had already introduced a bill with the proposal, approved by both Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes and officials with the National Park Service. Even locals were on board.

The lone sticking point seemed to be the apparently uncontentious issue of buying out a few plots of private land along the coastline, an effort that would cost an estimated $500,000.

“For a half million dollars, [Oregon State Parks superintendent Samuel H. Boardman] believes the national government can acquire a playground of matchless grandeur,” the Oregonian reported.

So what happened? It’s not clear. The matter didn’t resurface in the Oregonian until 1960, when a poll found majority support for a national park among residents on the coast, and 1986, when Curry County commissioners resurrected the idea as a way to help the local economy, recently ravaged by mill closures and cycles of harsh weather.

In the end, the Oregon Coast National Park plan just fizzled out. So much is involved in designating a national park—from local support to approval from Congress—that all it takes is one stuck gear to stop a plan in its tracks. Much of the proposed Oregon Coast park did become a reality, but under a different designation completely: the Samuel H. Boardman State Scenic Corridor.

Not that “much” (see below). In another piece for the Oregonian (“In Search of the Lost Oregon Coast National Park”), Hale delved deeper into the failure to secure an Oregon Coast National Park:

I’m mystified. One day the park is a sure thing—supported by the governor, brought up in Congress, considered by the National Park Service—and the next day it’s gone. As if the proposal never happened.

Based on Oregonian articles, here’s a rough timeline of what happened with the park proposal.

In 1938, The Oregonian reported on an idea for a national park on the Oregon coast, highlighting its economic potential and beaming with pride about the “wild country.” The next year the proposal had “advocates” and was considered alongside two other potential national park sites in the state—Hells Canyon and Mount Hood.

By 1940 things had really heated up. In April, The Oregonian wrote at length about the state’s national park proposals, saying the establishment of a coastal park depended largely on local approval.

“To date local feeling on the coast park seems to be more favorable than toward any other new national park established in the far west in recent years,” The Oregonian reported. “Not only is [Gov. Sprague] favorable to the creation of the coast park, but he also adds that the proposal meets with the approval of Curry county.”

One month later, McNary introduced a bill into Congress that would establish the Oregon Coast National Park, a place, he wrote, that “embraces one of the most rugged and scenic portions of the Pacific coast, and is a practically unmodified area combining many outstanding geological and biological features.”

The bill went nowhere, but even if it had garnered interest that year, it’s unlikely that it would have made it much farther. The same month McNary introduced the park bill, Nazi Germany invaded western Europe. A year and a half later, on Dec. 7, 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Suddenly the United States had a lot more than national park sites to worry about.

Perhaps World War II was a factor, but Congress established Big Bend National Park in 1944. President Roosevelt found time to sign the bill six days after D-Day. Texans didn’t fail. Oregonians did.

Figure 6. Oregon’s first state park superintendent Samuel H. Boardman (1874-1953). Source: Oregon Encyclopedia.

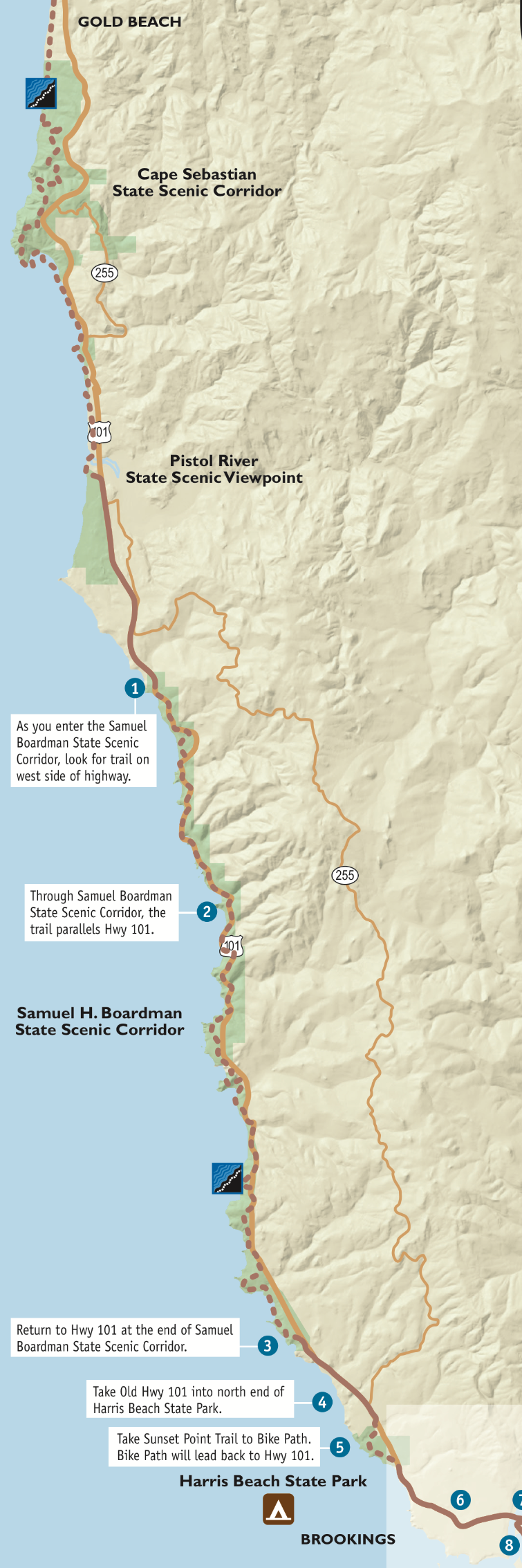

Sam Boardman (Figure 6), the father of Oregon state parks and a hero of mine, is responsible for four modest units of the Oregon State Parks System for which we are eternally grateful:

• Samuel H. Boardman State Scenic Corridor (1,147.01 acres)

• Cape Sebastian State Scenic Corridor (1,400.8 acres)

• Pistol River State Scenic Viewpoint (448.35 acres)

• Harris Beach State Park (174.21 acres)

These four state park units total 3,170.37 acres (Map 1), which is 10.57 percent of Sam’s vision for an Oregon Coast National Park (Map 2). As he didn’t have enough money, Sam’s acquisitions were often of the underlying land but didn’t include the standing timber. Sometimes livestock grazing continued. Boardman took the extremely long view as he was buying parklands in the 1920s, when there was no public demand as there is in 2020. What a visionary!

Map 1. What is. The light green along US 101 are the four modest Oregon state parks. Source: Oregon State Parks.

Map 2. What might have been. ~30,000 acres was proposed for an Oregon Coast National Park. For scale, the parcel is ~3 miles wide at its widest. Source: Jamie Hale, The Oregonian.

Oregon Dunes

Figure 7. The Oregon Dunes. Source: Dominic DeFazio (first appeared in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness).

The fight over the Oregon Dunes wasn’t really a fight for a national park but another kind of National Park System unit, a national seashore. The locals greatly feared the National Park Service. Hale writes:

At the end of the 1950s, the park service began looking into a national seashore, a lesser designation than a national park, at the Oregon Dunes on the central coast. Instead of the widespread support the national park proposal enjoyed, the proposed designation of the dunes inspired widespread debate. Even The Oregonian, an on-again off-again champion of the parks, was against this new idea.

“There has been a running fight on the Coast about the desirability of establishing a federal seashore,” a 1963 editorial said. “But we have not detected any burning interest among the bulk of Oregon’s citizens.”

The park service eventually established the Oregon Dunes National Recreational Area, but the decade-long controversy ensured that no park proposal at the coast would come easy.

Actually, Congress established the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area in 1972. About half is abused by off-road vehicles and about half is not.

Steens Mountain

Figure 8. Wildhorse Lake, Little Wild Horse Lake, and Wildhorse Creek Canyon on Steens Mountain. What you see is now protected wilderness and a wild and scenic river but is not a national park. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

Over many decades, the National Park Service has cast its bureaucratically lustful eye at Steens Mountain. Steens Mountain reeks of national park qualities. Yet, the Steens was never enough of a priority. It was too far away from the center of power in Portland.

In 2000, Congress established the 0.5-million-acre Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Area (it’s better than it sounds), the 174,744-acre Steens Mountain Wilderness (of which ~100,000 acres is statutorily livestock-free), and ~29 miles of additional wild and scenic rivers. Better than nothing.

Owyhee Canyonlands

Figure 9. The Owyhee Wild and Scenic River in the Owyhee Canyonlands Wilderness Study Area. Still time for an Owyhee National Park. Source: Bureau of Land Management.

The National Park Service has similarly lusted after portions of the Owyhee Canyonlands. There are parts of the Oregon Owyhee that look like they are in Utah canyonlands.

In 2016 an attempt for a presidentially proclaimed national monument failed. In 2020, horrible legislation was introduced that would change the color on the map more than the management on the ground, and otherwise exalt livestock grazing on 4.7 million acres.

Volcanic Cascades

Figure 10. The area from the foreground to Mount Jefferson in the background was within the proposed Volcanic Cascades National Park. Source: Gary Halvorson, Oregon Archives.

A 790,000-acre national park feels big (more than four times bigger than Crater Lake National Park), but it would have stretched from the Columbia River to Crater Lake. I have never seen a map of the proposal and cannot tell you if it was one rather and long narrow unit (which would have averaged a bit more than six miles in width, generally above the commercial timberline) or several units centered on the major snowy peaks.

From the April 25, 1969, Congressional Record:

S. 1947—INTRODUCTION OF A BILL AUTHORIZING THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR TO INVESTIGATE AND REPORT TO CONGRESS ON THE ADVISABILITY OF ESTABLISHING A NATIONAL PARK IN THE CASCADE MOUNTAIN REGION

Mr. HATFIELD. Mr. President.—.

“It is a magnificent sight. Behind the sharp, splintered uplifts of Mount Washington and Three Fingered Jack, Mount Jefferson rises in architectural perfection, complemented by the distant snowy cone of Mount Hood. Nearby, their fires only recently stilled, the Middle and South Sisters lift massively against the skyline. Beyond . . . many-summited Diamond Peaks . . . the calderal blue of Crater Lake.

“These are the shining mountains. Glacier-sheathed, they dominate a living wilderness of near-rain forests, volcanic wonders, calm lakes, rushing streams and flashing waterfalls, varied wildlife, and a diversified flora.”

So wrote David Simons in 1959, describing the Oregon Cascades. Nominated for national park status as early as 1916 in the State’s travel promotion and revered by Oregonians everywhere, these lands deserve the utmost care and protection.

I believe, Mr. President, that a detailed, impartial study of these lands in the Oregon Cascades should be made to determine whether portions thereof are of national park caliber. Therefore, I introduce today for appropriate reference a bill directing the Secretary of the Interior to study the scenic, scientific, recreational, educational, wildlife and wilderness values of the Oregon Cascades from the northern boundary of Crater Lake National Park to the Columbia River. Within 1 year of the enactment of the bill, after the detailed, impartial study has been completed, the Secretary of the Interior would make his report to Congress.

The bill is not a proposal to create a national park over such a large area. But realistically the whole area must be studied to determine which parts thereof should be included in a national park. In any event, the study will provide guidelines to protect this extraordinary area of “shining mountains.”

Is this the same Senator Mark O. Hatfield who left mostly a legacy of roaded and clear-cut forestlands across the state, along with several fish-killing pork-barrel concrete monstrosities damning our rivers? I didn’t know him then. (I was in the ninth grade.) For context, let’s hear from Larry Williams, then the executive director of the Oregon Environmental Council, testifying on Capitol Hill before Senator Frank Church’s famous “clear-cutting” hearings in 1971:

We are deeply concerned about the possibility of preserving some of the Oregon Cascades’ scenic beauty. This concern is not a new one. The first proposal for a National Park in the Oregon Cascades was made in 1916 by the Oregon Department of Mines and Geology. In 1937, Judge Sawyer, of Bend, proposed a National Park in the central Cascades, to preserve the magnificent douglas fir forest. The proposal was revived again in the late 1950’s after the Forest Service began its present program of eliminating de facto wilderness and after the commencement of logging in the high mountain areas. . . . One proposal, in 1959, by David Simons of Springfield, called for a Cascades National Volcanic Park of some 790,000 acres.

The growing awareness among Oregonians that something was very wrong with the management of the Oregon Cascades was evidenced, in 1968, by the introduction of a bill by former Senator Wayne Morse calling for a study of the Oregon Cascades by the Department of the Interior (s. 2555).

The hue and cry that was raised by the timber industry over the possibility of a management study of the Oregon Cascades was a sight to behold. One would have thought Senator Morse’s bill called for a complete halt to logging in the Cascade Range.

Unfortunately, Senator Morse’s study bill died in the Senate without any hearings being held. A new bill was introduced in the next Congress by Senators Hatfield and Packwood (S.4034), which called for a joint study of the Oregon Cascades by the Department of Agriculture and Interior. That bill also died without hearing being held.

We are very pleased to see a new bill has been introduced by Senator Packwood (S.881), which calls for [a] completely independent study of the Cascades (i.e. neither the Department of Agriculture nor the Department of the Interior would participate as members of the study team). Again, the forest industry has expressed opposition to a study bill but this time they oppose the bill because the Department of Agriculture cannot participate in the study. It is obvious that the timber industry is very fearful of any attempt at a management study of our Volcanic Range.

We urge Senator Hatfield and all Oregon Congressman to support a study of the Cascades to discover just why the forest industry is so fearful of a study of the Cascades. If they have nothing to hide, then the study should be welcomed by all.

Figure 11. Mount Washington from Big Lake. Source: Wikipedia (Forest Service).

In Part 3, we will examine the two modest expansions of Crater Lake National Park and more bold proposed expansions that failed.

Acknowledgment

I am greatly indebted to Jamie Hale of the Oregonian (I refuse to call it oregonlive.com, but mark my words, the name change will be finalized soon) for his reporting on Oregon’s lost opportunities for additional national parks. His posts are almost always of interest to those of us who worship and enjoy Oregon’s natural wonders.