I’m generally not a fan of Representative Chris Stewart (R-UT-3rd), who has a lifetime record of voting right on conservation issues just 3 percent of the time, according to the League of Conservation Voters. Now, though, he’s introduced a bill in the House that has merit. Stewart’s proposed Advancing Conservation and Education Act (aka ACE Act, H.R.244; 116th Congress) had a hearing in the Subcommittee on National Parks, Forests, and Public Lands of the House Committee on Natural Resources on June 18, 2020.

Figure 1. Representative Chris Stewart (R-UT-3rd). Source: Wikipedia.

The stated purpose of the bill is to “maximize land management efficiencies, promote land conservation, generate education funding, and for other purposes.” Who could be against the purposes expressed? But while the intent is excellent, the execution needs improvement.

The Problem Addressed by the Bill

The problem addressed by the bill is well explained in the findings section. Following is a list of the findings, with my commentary on each.

Congress finds that—

(1) at statehood, Congress granted each of the western States land to be held in trust by the States and used for the support of public schools and other public institutions;

A future Public Lands Blog post will examine state trust lands in detail, but for now suffice it to say that states carved out of the public domain were granted significant amounts of land upon achieving statehood. The granted lands were a varying number of 1-square-mile sections in each 36-square-mile (6-by-6-mile square) township. The amounts increased so that the most recent states received the most land (save for Hawai’i).

(2) since the statehood land grants, Congress and the executive branch have created multiple Federal conservation areas on Federal land within the western States, including National Parks, National Monuments, national conservation areas, national grassland, components of the National Wilderness Preservation System, wilderness study areas, and national wildlife refuges.

Any executive branch actions were done under authority expressly granted by Congress. I wouldn’t consider a national grassland to be a federal conservation area, but whatever.

(3) since statehood land grant land owned by the western States are [sic] typically scattered across the public land, creation of Federal conservation areas often include [sic] State land grant parcels with substantially different management mandates, making land and resource management more difficult, expensive, and controversial for both Federal land managers and the western States;

Yep.

(4) allowing the western States to relinquish State trust land within Federal conservation areas and to select replacement land from the public land within the respective western States, would—

(A) enhance management of Federal conservation areas by allowing unified management of those areas; and

(B) increase revenue from the statehood land grants for the support of public schools and other worthy public purposes.

Amen on (A), but (B) can be achieved in a better way. The states should be given money, not federal public land, for their stranded assets within federal conservation areas.

Figure 2. A good—but not yet great—bill. Source: Congress.gov.

The Solution to the Problem

Land exchanges are the wrong approach because land exchanges are almost always controversial (all federal public lands have their constituencies). Rather than trade the stranded state lands for federal public lands elsewhere, the federal government should buy the lands over the next several years. If the states are given money for their lands, they can choose to invest the money in more land, or they can invest in another instrument that might offer a higher rate of return—resulting in more money for education.

How much money are we talking about to buy the stranded lands? The National Association of State Trust Lands (NASTL, formerly the Western State Land Commissioners Association) estimates that “there are nearly two million acres of trust lands and minerals trapped” in federal conservation areas.

Ryan Brunner, the South Dakota Commissioner of Schools and Public Lands and NASTL president, tells me that the problem is most acute in Arizona (~267,000 surface and subsurface acres and ~239 subsurface mineral acres), Wyoming (~240,000 acres), and Utah (~250,000 acres). He says that there are large amounts of stranded state lands within federal conservation areas in Alaska, New Mexico, and Colorado. He notes there are also trapped lands in California, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. The NASTL survey was nearly a decade ago, so the two million acre number is probably higher as federal conservation areas have increased since then.

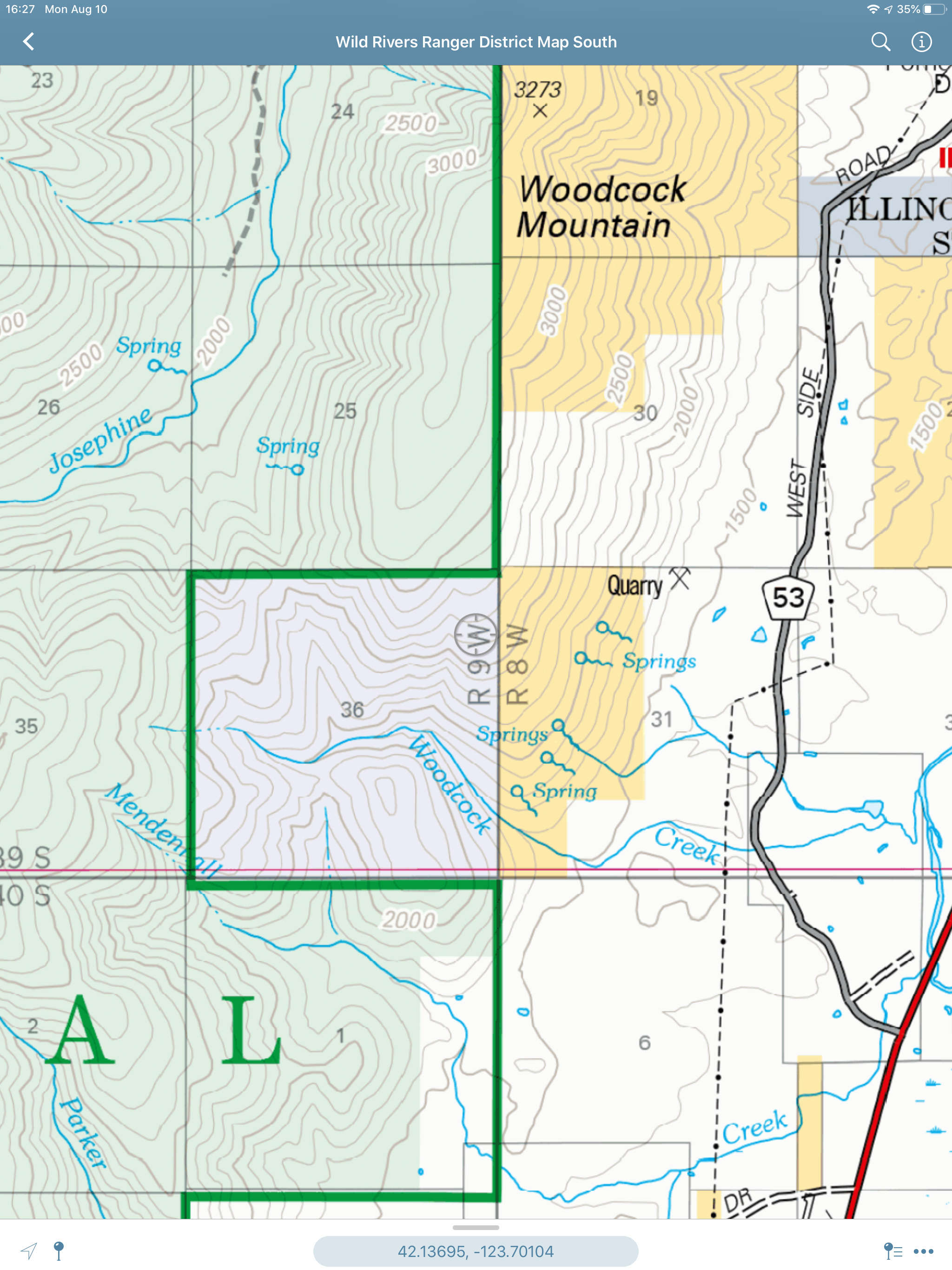

See Map 1 for a typical example of state lands within a federal conservation area. Let’s very generously assume that the average market value of an acre of stranded state lands is $500. (Much of the state land acreage within federal conservation areas is of low economic value, as is much of the federal public land in those areas). $500/acre * 2 million acres = $1 billion.

Map 1. The 99,428-acre Cedar Mountain Wilderness (green) was established in 2006 on lands administered by the Bureau of Land Management (tan). The hatched and blue squares are State of Utah lands. If only hatched, the state owns only the subsurface minerals. The pink is a military reservation. Source: Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration.

The money for the federal government to buy the stranded state lands can come from the federal Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), first established in 1965. Between 1965 and 2019, $40.9 billion went into the LWCF, while Congress spent only $18.9 billion. On average, Congress has been spending $407 million from the fund each year. The Great American Outdoors Act signed by President Trump on August 4, 2020, guarantees $900 million a year in funding for the LWCF. Setting aside the question of the unspent backlog, annual spending will now more than double. The new law says that if Congress doesn’t spend the funds in congressional appropriations bills, the federal agencies can spend them without further approval of Congress.

The ACE Act should be modified to require that $100 million of the projected average of $593 million of new annual LWCF funding be spent each year acquiring state lands in federal conservation areas until all such lands are again federal public lands.

What are the political chances? Representative Stewart, whose idea the bill was, is in the minority in the House of Representatives at the moment (fortunately!). But Stewart is a member of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee. The chair of that subcommittee is Representative Betty McCollum (D-MN-4th), a staunch public lands conservationist (rated as a 94 percent lifetime correct voter by the League of Conservation Voters). Now, a McCollum-Stewart bill offers a chance for both representatives to leave an enduring legacy of conservation and education.

Figure 3. Representative Betty McCollum (D-MN-4th). Source: Wikipedia.

Time for the Public Lands Conservation Community to Step Up

Some of my cynical conservationist friends may suggest that it’s not important to acquire these stranded state lands because they are indeed stranded and therefore under no threat of despoliation. To them I would say:

• Conservationists or our predecessors bled to get these areas established as federal conservation areas. The job is not done until they are entirely federal public land.

• It’s the right thing to do morally. Through no fault of their own, the states have these stranded assets that are dedicated for public education.

• It’s the right thing to do politically. As conservationists seek additional federal conservation areas, the presence of scattered state land holdings is often a political obstacle. Having an established and reliable mechanism for converting problematic state lands into higher conservation value federal public lands can result in more and larger federal conservation areas. (It’s a great day when the moral thing and the political thing coincide!)

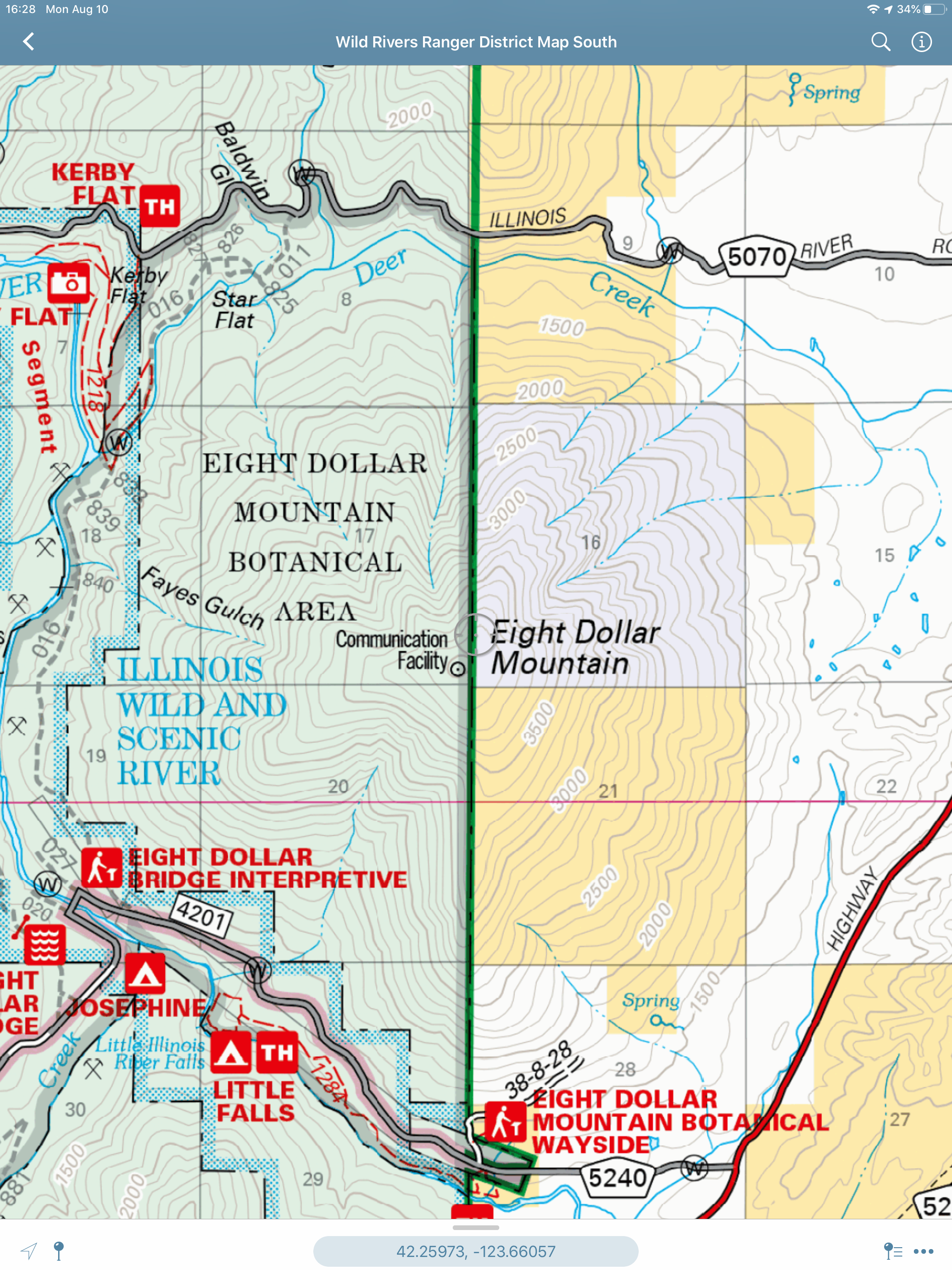

State Trust Lands in Oregon Worth Acquiring by the Feds

Let’s close with some maps of various State of Oregon Common School Fund sections on and near national forests in southwest Oregon. These lands should also be acquired by the federal government for the benefit of this and future generations. There are other Oregon examples as well as similar cases in most of the western states.

Map 2. The lone state section (purple) is surrounded mostly by the Umpqua National Forest and Bureau of Land Management holdings. It is adjacent to the South Fork Cow Creek Unroaded Recreation Management Area. Conservationists are recommending that Senator Wyden introduce legislation making the South Fork of Cow Creek a wild and scenic river. Source: US Forest Service.

Map 3. The BLM land to the east of the state section is a research natural area and area of critical environmental concern. The Forest Service land on three sides is inventoried roadless area. Source: US Forest Service.

Map 4. Though the Minnow Creek Trail never comes within a mile of Minnow Creek, it’s still an important trail. The trailhead is on State of Oregon land that is surrounded on four sides by federal public lands. The trail is in the 3,423-acre Buckhorn Mountain Uninventoried Roadless Area. Source: US Forest Service.

Map 5. The BLM land to the east of the state section is a research natural area and area of critical environmental concern. The Forest Service land to the west is a protected area. The Nature Conservancy owns the adjacent private lands. It’s all a botanical wonderland. Source: US Forest Service.

Map 6. Conservationists are recommending that Senator Wyden introduce legislation making the South Fork of Sixes River a wild and scenic river. If this status is established, the state land would be within the protected corridor but not protected, as it is not federal public land. Source: US Forest Service.

Map 7. Senator Jeff Merkley has introduced legislation to expand the Smith River National Recreation Area into Oregon. Besides adding the Cedar Creek tributary (and many others!) to the North Fork Smith Wild and Scenic River, the legislation would facilitate conversion of the state parcel to federal ownership. Senator Ron Wyden is cosponsoring the legislation. Source: US Forest Service.