This is the second of a three-post examination of forests in the American East. Part 1 diagnosed an “environmental generational amnesia” that makes people think it is okay to not have real (old-growth) forests and to tolerate, if not facilitate, massive and repeated clear-cutting and/or deforestation in the name of creating “early successional habitat” for species of wildlife that we need not be concerned about. This Part 2 sheds light on a conspiracy of self-interested timber companies, misguided public land foresters, misinformed wildlife biologists, and Kool-Aid-drinking conservationists. Part 3 will suggest ways to partially—but significantly—bring back the magnificent old-growth forests that have long been lost.

Figure 1. The Penobscot Experimental Forest in Maine. The forests of the American East can be quite beautiful, but they are almost all quite puny shadows of their former selves. Source: US Forest Service.

There is a conspiracy to keep forests in the American East forever young or nonexistent, driven by corporate greed, bureaucratic self-interest, and good—but misguided—intentions. It involves timber companies, game bird hunters, deer hunters, state wildlife agency managers, Forest Service land managers, and even conservation organizations. All these interests (well, maybe not Big Timber) suffer from shifting baseline syndrome, described in Part 1. For different reasons, these partners have joined forces to log and burn any recovering forest in the American East back to its early successional habitat stage.

For this Part 2 in most particular, I am greatly indebted to the authors of the instant classic scientific paper “Forest-Clearing to Create Early-Successional Habitats: Questionable Benefits, Significant Costs” (Kellett et al. 2023.) Almost every fact asserted herein generally comes from this tour de force. Kellett et al. first detail the magnificent original forests of New England, the mid-Atlantic states, and the upper Great Lakes states; continue with what those forests have been reduced to today; then detail a conspiracy against real and old forests; and conclude with a vision of how to recover much of the carbon storage and sequestration, biodiversity, watershed, and social benefits that have been lost. This post will recap the first three of those topics, and the next post will address the fourth.

Figure 2. Virgin forest in 1620 in what would become the eastern United States. Source: Chief William B. Greeley, US Forest Service (1920).

First, Some Terminology

To help you better understand what’s at stake in the forests of the American East, I will first define some descriptive terms.

A primary forest has never been logged and is likely to be old-growth forest because such is the normal case.

An old-growth forest could have previously been logged but has gotten old enough to acquire the complex structure, composition, and function characteristic of old forests. In the American West, all old-growth forest is also primary forest. In the American East—because European settlement came far earlier and was far faster—there is an infinitesimal amount of primary forest and only slightly more old-growth forest.

In the American East of today, a mature forest is one that has—in all likelihood—been logged at least once but is on the path toward old growth again. Most mature forests are on public lands, either national or state parks or forests.

In the American East, young forests abound, a result of logging on private, state, and federal lands. Young forests are stands that have a closed canopy but are not yet mature forests.

The state of forest development that precedes a young forest is early successional habitat (ESH) or preforest. While very abundant, ESH is often a very simple forest, with fewer species and less biological diversity than a complex ESH that occurs after a stand-replacing or stand-opening event. Before the European invasion in the American East, forests that were naturally regenerating after a stand-replacing event ranged from 1 to 10 percent of the land at any particular time. It was mostly less than 10 percent, but advocates of early successional habitat have seized on 10 percent as the figure they use. The truth is that originally, a.k.a. in 1620, ESH was rather rare, covering far less than 10 percent of the land area. Such preforest was also complex in structure, composition, and function. Today’s ESH is quite excessively abundant in area and simplistic in structure, composition, and function.

Finally, there is a variant of young forest that is an industrially imposed monoculture plantation of one species, more akin to a cornfield than a forest.

Figure 3. A straight-up example of gap dynamics in a forest stand. (The swordlike leaves on one tree tell us this opening is in the Amazon, but the old-growth forests of the American East used to have a lot of such openings.) Source: Wikipedia (Irina Skinner).

In the “Beginning”: Forests, Forests, Everywhere

Before the European invasion, most of the land in the Northeast was forested, and most of those forests (up to 90 percent) were old-growth forests. Whatever their age, having never been logged, these vast forests were primary forests. Old growth made up 50 to 60 percent of the forests on the Upper Great Lakes region and 40 to 50 percent in the Southern Great Lakes region.

Such old-growth forests were very long-lived and full of carbon and biodiversity. Large temporary disturbances to the old growth came mainly from wind and ice storms, and sometimes fire. Stand-replacing events, common to forests in the American West, were relatively rare. Most forests in the American East were older than any of the trees within them.

Anywhere from 1 to 4.5 percent of Northeast forests naturally consisted of early successional habitat (ESH), more in the coastal pine barren forests of today’s Cape Cod, Long Island, and New Jersey. Countless relatively small, both permanent and temporary, openings existed in the otherwise continuous forest canopy. According to Kellett et al., the permanent gaps were “associated mainly with cliffs and scree slopes, ridge tops, wetlands, peat bogs, serpentine barrens, avalanche tracks, river margins, pond and lake margins, and coastal shrublands and bluffs.” The smaller temporary gaps were caused by micro-size wind-caused blowdowns of one or more trees (Figure 3). Such transitory openings in the dense forest canopy offer habitats critical to the thriving of certain species.

Kellett et al. note that Native peoples “practiced subsistence hunting, fishing, and plant gathering, as well as burning and small-scale farming.” Their overall impact on the vast forests of what would become the American East was minimal to none. Before the European invasion, the number of Native people living in the Great Lakes region and the Northeast “was less than 1 percent of the current population and largely centered along the coast and in major river valleys, with localized and modest impacts across most of the region.”

Figure 4. Virgin forest in 1850 in the eastern United States. Source: Chief William B. Greeley, US Forest Service (1920).

Invasion of the Europeans: Massive Deforestation

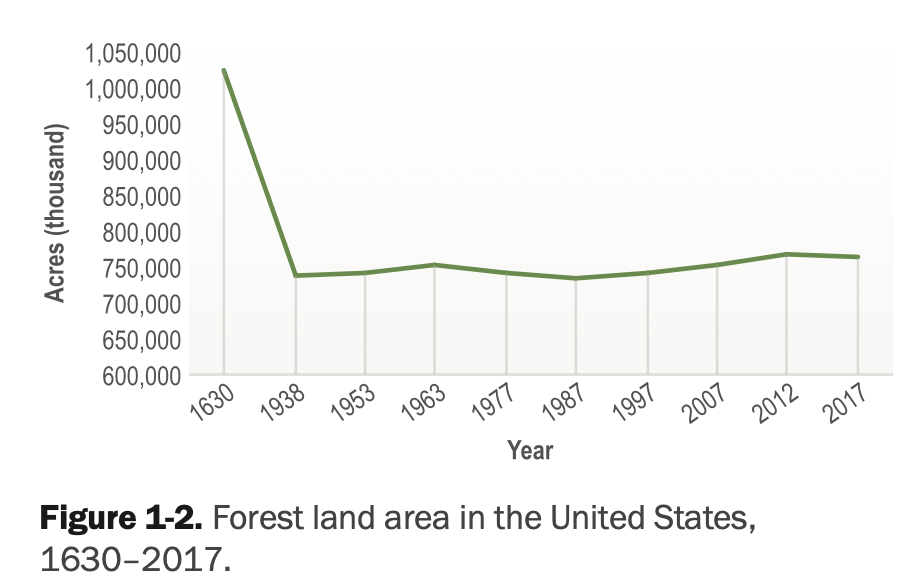

As soon as the Europeans arrived in North America, the loss of forests began. Between 1630 and 2017 in the American East, 41 percent of the original primary forest was permanently converted to cities, farms, and other human infrastructure. (In comparison, forest cover in the American West declined 7 percent between 1630 and 2017.) Kellett et al. found that by the height of deforestation (1850 to 1880), 30 percent of northern New England and 40 to 50 percent of southern New England had been cleared; by 1920 more than 90 percent of the Upper Great Lakes region was cutover.

Figure 5. Virgin forest in 1926 in the eastern United States. Source: Chief William B. Greeley, US Forest Service (1926).

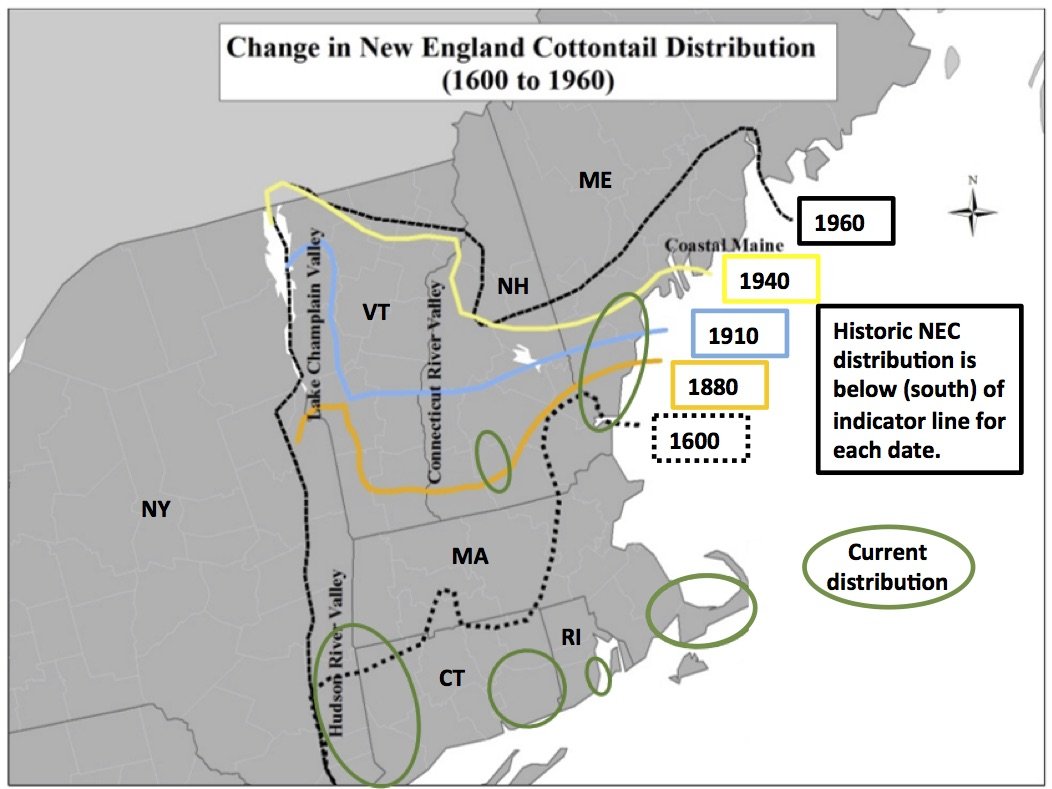

As the forest changed from old growth to young or no forest (grazing and crop land)—and hunting increased—many common species of wildlife were lost. Wolves, mountain lions, turkeys, moose, deer, and passenger pigeons declined dramatically, sometimes to extirpation or even extinction. At the same time, as old-growth forest gave way to farms, several wildlife species that were originally uncommon—except in very special and limited habitats—became very common. Species including but not limited to the bobolink, eastern meadowlark, gold-winged warbler, yellow-breasted chat, and New England cottontail all dramatically expanded both their ranges and their numbers.

Figure 6. Changes in land cover and wildlife dynamics in New England from ∼1600 to 2000. Notice the inverse relationship between bobolink and meadowlark levels and the amount of forest. Notice that even though forests never zeroed out, passenger pigeons did. Notice how as goes the forest, so go moose, deer, beaver, and turkey. Source: Kellett et al. 2023, adapted from Foster et al. 2002.

Figure 7. Deforestation since the 1600s has allowed the New England cottontail to expand from its original range (black dashed line). As the landscape becomes more forested, the artificially high numbers of cottontails are reversing. Source: Adapted from US Fish and Wildlife Service information (2015).

Figure 8. Area of virgin forest in the Northeast today. Look hard to see the dots, each of which represents 25,000 acres. Such acres are spread among very numerous very small groves. Not by, but after the style of, Chief Greeley. Source: vividmaps.com.

Today’s “Forests”: Less Quantity, Very Low Quality

Big Timber likes to brag that there is more forestland today than in 1900 and that there are more trees in those forests. While not untrue, this claim is misleading. All forests are not created equal.

Figure 9. The brighter the green, the more carbon in the forest. While 89 percent of Maine is still “forested,” such forests are extremely puny, certainly compared to what once was but also to what is elsewhere in New England and the Northeast. Source: US Forest Service Carbon OnLine Estimator.

Figure 10. Forest land area in the United States, 1630–2017. While the area of forest cover has been relatively stable since 1938, this tells us nothing about whether an acre of forest is old growth or an industrial monoculture plantation; far more likely the latter than the former. Source: USDA Forest Service, Forest Resources of the United States, 2017.

While forest cover in the American East has stabilized in quantity, quality is quite another matter. Once primarily old-growth forests, the remaining forestlands in the American East are now mostly young and mature forests that have been logged several times.

Figure 11. Current state of forestlands in New England. Although it looks like there’s lots of forest (the green areas), that forest is rather short in stature, small in diameter, and severely lacking in carbon. Less than 5 percent of that forest is intact (the yellow and red areas), topping out at 4.5 percent in New Hampshire. The areas of protected intact forest (red) include Baxter State Park in north-central Maine and a few wilderness areas in Vermont and New Hampshire. Source: Moomaw et al. 2019.

The American East is nearly devoid of old-growth forests. As Kellett et al. note:

In the Northeast, forests older than 150 years of age cover only about 0.3% of New England and 0.2% of the Mid-Atlantic region. Old-growth forests cover a scant 0.06% of Connecticut. A Massachusetts survey found a mere 1,100 acres of old-growth forest in 33 small stands, comprising just 0.02% of the land base. Most of the old-growth forest in the Northeast is found in the Adirondack and Catskill parks in New York. In the Upper Great Lakes region, only about 1.9% of the currently forested area remains as primary forest that was never logged. Including secondary forests, approximately 5.5% of the northern hardwood forest type is older than 120 years of age, compared to 89% in the presettlement forest; for red-white pine this is 2.5% versus 55%. For all forest types, about 5.2% is old-growth compared with 68% before European settlement. [citations omitted]

The Conspiracy: Based on Species of Concern That Should Not Be

In a world of little good news, it’s nice to know that on the whole, forests in the American East are increasing both in area and age. As these forests return toward what was once the norm, certain bird and other species are in serious decline—if your reference point is the 1960s. Remember shifting baseline syndrome? If your reference point is, say, 1630, these “species of concern” are not really species of concern.

If you look over state wildlife action plans (SWAPs; necessary for federal grants) for northeastern and Great Lakes states, you find they have identified species of conservation concern that require early successional habitat. These species include but are not limited to bobolink, eastern meadowlark, golden-winged warbler, yellow-breasted chat, and New England cottontail. Recall that these are the species whose populations surged in the wake of massive deforestation.

Figure 12. The bobolink is a faux species of concern. Its numbers have declined from the peak of New England deforestation and are returning to historically lower levels as today’s forests continue to mature. Source: Wikipedia.

In this narrative, the forests of the American East must be kept puny to support faux species of concern and the interests of several pitiful parties to the conspiracy.

Pity the poor timber companies. The public is increasingly intolerant of clear-cutting, especially on public land (state or federal), which has been bread and butter to these companies. The companies need to convince the public that logging is good for wildlife.

Figure 13. A fifteen-year-old loblolly pine plantation in the American Southeast. Economically, this “stand” of “forest” is overmature in that an industrial economic rotation is ten to twelve years. Besides, it is rather unsightly, as close inspection will reveal a few small dead branches lying on the ground. Source: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Pity aging game bird hunters. There are far fewer ruffed grouse and American woodcock than when they first hunted. Not only were there more birds to shoot then, but there was also more open habitat in which to see and shoot. Aging forests close their canopies, which isn’t good if you want to shoot grouse and woodcock.

Figure 14. A male ruffed grouse looking for love. Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Pity the poor deer hunters. If there is less ESH, there will be fewer deer to shoot. Not that there is any dearth of deer to dispatch! Due to a paucity of large predators in the American East, deer numbers are far in excess of carrying capacity, and they are a prime vector for ticks that carry Lyme disease.

Figure 15. An American woodcock. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Pity the poor state wildlife agency managers. While they may personally care about species not hunted and/or species dependent upon older forests, that’s not where the money is for their agency. Much of their budget comes from state hunting licenses and tags or from federal excise taxes on guns, ammunition, and fishing gear. Revenues from the former have been flat or declining as citizens become more urbanized and hunt and fish less (but bird more), even as agency revenues from federal excise taxes are up significantly as people buy more guns and ammo—less for hunting these days and more for self-defense and crime. Seventy-one percent of privately owned forests in the American East are owned not by corporations but rather owners who value their forests for things other than board feet, many of whom are not resistant to letting their forests grow to old age again. Yet, for the sake of the agency budget which is severely weighted toward game species that can be most easily produced in early successional habitat, state wildlife agency managers advise private landowners to log their lands for the benefit of these game species rather than suggest not logging them for the benefit of species dependent upon older forests (not to mention the benefit to the climate).

Figure 16. Former oak trees killed in the name of early successional habitat on New Jersey’s Sparta Mountain “Wildlife” Management Area. Source: Joan Maloof.

Pity the poor Forest Service land managers. They are stuck in the past, thinking that foresters improve forests by logging them and that timber production is an important use of national forests in the American East. Most American don’t like clear-cutting, so the Forest Service land managers gussy it up by calling clear-cuts early successional habitat. Unfortunately, Congress has given them plenty of money for such mischief.

Figure 17. A clear-cut on the Ouachita National Forest. Source: Mark Drummond, US Geological Survey.

Pity the poor conservationists volunteering with or working for a conservation organization. The birds they have long noticed are becoming less noticeable. Urbanization is eliminating any habitat wholesale. Can existing habitat be “improved”? Rather than fight for what is hard—the restoration of old-growth forests—too many conservationists fight for what is easy—favoring logging in the name of birds and other species that are not in trouble.

The face of this conspiracy of pitiful parties is the Young Forest Project (“Growing Wildlife Habitat Together”). Kellett et al. note that the website for this project was inaugurated in 2012 to persuade target audiences and within a decade had recruited more than a hundred partners. (You can download a list of Young Forest Initiative Partners.) These include timber companies like Weyerhaeuser; federal and state forest agencies including the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and the USDA Forest Service; federal and state wildlife agencies including the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection; and sportsmen’s groups such as the Ruffed Grouse Society/American Woodcock Society and the National Wild Turkey Federation. Most troubling is the participation of certain conservation organizations, including but not limited to the American Bird Conservancy and several Audubon state groups (New York, Connecticut, Vermont, and New Jersey).

According to Kellett et al., “All of these partners benefit from forest-clearing through increased profits from timber sales, larger agency budgets, more staff, direct payments for creating young forest habitat, or elevated populations of desired game species.” Conservationists don’t care much about game species but care too much about other wildlife species that are less numerous than in recent history but are still above historical levels.

The Young Forest Project seems to suffer from shifting baseline syndrome, as do most of its partners. To hear the Young Forest Project tell it:

Forest Doesn’t Stay Young Forever

In most cases, young forest lasts only 10 to 20 years before it becomes older forest, often less useful to wildlife.

Branding a forest that couldn’t legally drink if it were a human as an “older forest” is quite the shifted baseline. It seems we have a case of not being able to see the forest for the stumps. Actually, it’s more a case of not being able to see the older forest because it hardly exists to be seen.

Figure 18. Forest succession typical in the American Northeast. Many foresters and wildlife managers contend there is not enough habitat less than twenty-five years of age. Most forests in the American East are twenty-five to one hundred years of age. Very little forest today is between one hundred and two hundred years old. The amount of two-hundred-plus-year-old forests is ecologically priceless even if statistically insignificant. Source: Nicolle R. Fuller.

The Young Forest Project says, “Today we have more than enough older forest in our region” and also “Yet recent conservation efforts in the East have focused mainly on preserving older forest, of which many thousands of acres have been protected.”

Buckle up, people. It’s time to add three zeros to the conversation and talk not “many thousands” but many millions of acres that must be protected—to again be old-growth forests.

In Part 3, we will suggest some ways to broadly reestablish old-growth forests in the American East for the benefit of the climate, nature, watersheds, and this and future generations of people.

For More Information

Climate Forests coalition. July 2022. Worth More Standing: 10 Climate-Saving Forests Threatened by Federal Logging (pdf).

———. November 2022. America’s Vanishing Climate Forests: How the US Is Risking Global Credibility on Forest Conservation (pdf).

Kellett, Michael J., Joan E. Maloof, Susan A. Masino, Lee E. Frelich, Edward K. Faison, Sunshine L. Brosi, and David R. Foster. January 2023. Forest-Clearing to Create Early-Successional Habitats: Questionable Benefits, Significant Costs. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 5:1073677.

Leverett, Robert T., Susan A. Masino, and William R. Moomaw. May 2021. Older Eastern White Pine Trees and Stands Accumulate Carbon for Many Decades and Maximize Cumulative Carbon. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 4:620450.

McKibben, Bill. April 1995. An Explosion of Green. The Atlantic.

Moomaw, William R., Susan A. Masino, and Edward K. Faison. June 2019. Intact Forests in the United States: Proforestation Mitigates Climate Change and Serves the Greatest Good. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change 2:00027.

Oswalt et al. 2019. Forest Resources of the United States, 2017. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report W0-97.