This is the third of a three-post examination of forests in the American East. Part 1 diagnosed an “environmental generational amnesia” that makes people think it is okay to not have real (old-growth) forests and to tolerate, if not facilitate, massive and repeated clear-cutting and/or deforestation in the name of creating “early successional habitat” for species of wildlife that we need not be concerned about. Part 2 shed light on a conspiracy of self-interested timber companies, misguided public land foresters, misinformed wildlife biologists, and Kool-Aid-drinking conservationists. This Part 3 suggests ways to partially—but significantly—bring back the magnificent old-growth forests that have long been lost.

Figure 1. Old-growth cypress forest in the Loxahatchee Wild and Scenic River, Florida. Source: George Wuerthner.

Enough of the early successional habitat already. It’s a matter of balance. The forests of the American East have early successional habitat (ESH) far in excess of what was natural and is desirable. Between logging on private lands and permanent energy corridors (Figure 2), we have plenty of ESH.

Figure 2. Very wide and very long swatches of early successional habitat, otherwise known as gashes through the forest. The East will always have this kind of early successional habitat. Source: Wikipedia Commons.

Public forests should be mostly old-growth forest. Only 19 percent of all forestlands in the American East are public, with 9 percent in federal ownership (mostly national forests, national wildlife refuges, and military facilities). It’s going to take centuries for these forests to reach old-growth status, so we haven’t a moment to waste.

State and Federal Forest Agencies Out of Control

Since the end of World War II, the Forest Service has (and most foresters have) asserted (and practiced) that the solution to any problem is the chainsaw.

Figure 3. Forest Service propaganda sign: “COMMERCIAL CLEARCUT: Mature trees were harvested. A new hardwood forest will grow from the seedlings and seed in the forest floor. George Washington National Forest.” Source: US Forest Service.

Timber supply for returning WWII veterans? Log it. Jobs? Log it. Some dying trees (also known as old-growth forests)? Log it.

Figure 4. Old-growth eastern white pine in Rock Pond–Pharaoh Pond Wilderness in Adirondack State Park, New York. Source: George Wuerthner.

Forest fires? Log it (before, after, and also during). Natural episodes of insects and diseases? Log it. Fallen logs in streams as a barrier to fish passage (not!)? Log it.

Figure 5. The Hermitage, a very relic grove of old-growth eastern white pine in Maine. Source: George Wuerthner.

Stand-replacing fires, hurricanes, or volcanoes (that create ecologically complex preforests)? Log it (ideally before, but certainly after). Need for an increased water supply? Log it.

Figure 6. Old-growth eastern hemlock in Linville Gorge Wilderness, Pisgah National Forest, North Carolina. Source: George Wuerthner.

Forests stressed by climate change? Log it. Forests stressed by fire suppression (caused by the Forest [dis]Service)? Log it. Increasing the rate of carbon sequestration in forests (through accounting legerdemain)? Log it!

Figure 7. Old growth in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee. Source: George Wuerthner.

A decline in certain species of wildlife due to cutover forests growing back? Log it. A decline in certain species of wildlife due to a lack of old forests? Log the existing forest and dedicate what grows back to be old growth someday.

Figure 8. North Pond on the Green Mountain National Forest. The Forest Service is moving to sell the Telephone Gap timber sale, which will clear-cut much of the surrounding mature and old-growth forest in the name of early successional habitat. Source: John Geery.

Tomorrow’s Eastern Forests

We inherited the forests we have and had no choice in the matter. However, we have a choice as to the forest legacy we leave. I have a few ideas.

Figure 9. Don’t forget to look down while you are looking up and around in an old-growth forest. Source: George Wuerthner.

Proforestation

Forests should be allowed to age naturally. Like a good single-malt scotch, the older the better. Fundamentally, it’s all about letting the forests we have today grow older. Far older. To old growth. In a 2019 journal article, Tufts University professor Bill Moomaw, Trinity College professor Susan Masino, and Highstead Foundation senior ecologist Ed Faison coined the term proforestation.

The recent 1.5 Degree Warming Report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change identifies reforestation and afforestation as important strategies to increase negative emissions, but they face significant challenges: afforestation requires an enormous amount of additional land, and neither strategy can remove sufficient carbon by growing young trees during the critical next decade(s). In contrast, growing existing forests intact to their ecological potential—termed proforestation—is a more effective, immediate, and low-cost approach that could be mobilized across suitable forests of all types. Proforestation serves the greatest public good by maximizing co-benefits such as nature-based biological carbon sequestration and unparalleled ecosystem services such as biodiversity enhancement, water and air quality, flood and erosion control, public health benefits, low impact recreation, and scenic beauty. [emphasis added]

Figure 10. Mature, going on old-growth, forest in the proposed Telephone Gap timber sale on the Green Mountain National Forest in Vermont. Source: Sarah Stott.

Real Preforests, Not Simplistic Early Successional Habitats

While rare, complex early successional habitat (aka preforest) was a real stage in the life cycle of forests in the American East. The occasional fire or hurricane did take out a whole stand, but mostly complex ESH came from a massive number of microdisturbances in a stand. One tree or several fell and created a little opening that lasted a while and was favored by certain wildlife species. Almost all the current (and planned) ESH is simplistic in that almost all of the commercially valuable trees are removed from the site. In a natural preforest, a legacy of live and dead and standing and fallen trees is fundamental to the structural, compositional, and functional complexity of the site.

Figure 11. Ancient eastern hemlocks in the Green Mountains of Vermont. Source: George Wuerthner.

Very Large Nature Preserves

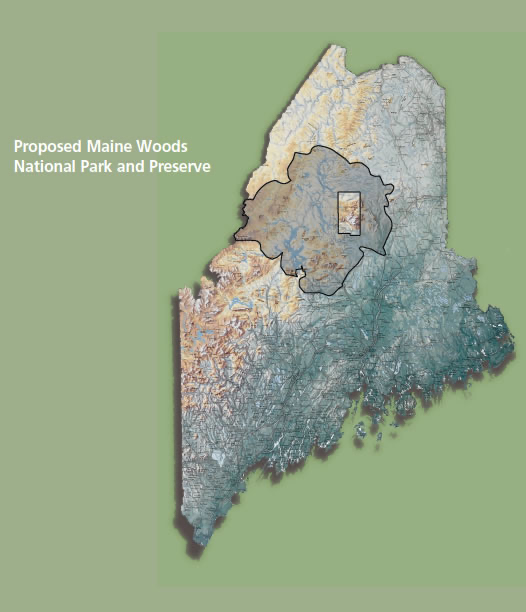

The taming of the wild East in the United States came early, well before the idea of very large nature preserves such as Yellowstone National Park, established in 1872. Few very large nature preserves exist in the American East. This needs to change, starting—but certainly not ending—with a Maine Woods National Park and a White Mountain National Park in New Hampshire.

Figure 12. Conservationists need to think and act with more zeros in their goals. The proposed Maine Woods National Park, which would encompass 3.2 million acres. The tall rectangle within it is Baxter State Park at 0.209501 million acres. Directly to the east of the state park but not shown on the map is the Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, proclaimed by President Obama in 2016. At 0.087583 million acres, the national monument is two-fifths the size of Baxter State Park. Source: RESTORE: The North Woods.

Tonnes of National Wildlife Refuges

To achieve the scientifically essential goal of conserving 30 percent of the nation’s lands and waters by 2030 (aka 30x30)—on the way to 50x50—a large amount of natural, somewhat natural, and naturally recoverable private lands needs to become public lands within the National Wildlife Refuge System. The forests in these refuges for wildlife should be allowed to grow old—not burned or brushed back as they often are now.

Figure 13. A telltale indicator of an old-growth forest: large boles of downed wood. Source: George Wuerthner.

See my three Public Lands Blog posts on the National Wildlife Refuge System: Part 1: An Overview, Part 2: Historical Evolution and Current Challenges, and Part 3: Time to Double Down.

Conserving Mature Forests to Allow Them to Be Old-Growth Forests Again

Due to the history of national forests in the American East, there are public lands that contain large amounts of mature forests that—if left alone—could again become old-growth forests. Conservationists are urging the Biden administration to promulgate an administrative rule that would protect all mature and old-growth forests and trees on federal forest lands. See Public Lands Blog posts “Biden’s Executive Order on Forests, Part 1: A Great Opportunity and Biden’s Executive Order on Forests, Part 2: Seize the Day!

Figure 14. Cemeteries: a refuge for old-growth trees. Source: George Wuerthner.

Filling in the National Forests of the East: Reinvigorating the Weeks Act

The fact that we have any national forests in the American East is thanks to Massachusetts Republican US Representative John Wingate Weeks (1860–1926). The Weeks Act of 1911 allowed the Forest Service to establish national forests that were not first carved from the public domain as in the American West. Where there is a national forest in the East, one can thank a visionary state legislature that had to approve such before the Forest Service could buy the land. It’s not too late for the legislatures of Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Maryland, and Delaware to be visionary. The law is still on the books. If they are politically afraid to be that visionary, legislators could vote to establish more state forests, but that might entail spending state rather than federal money.

Figure 15. Old-growth eastern white pine on the bank of the Oswegatchie River in the Adirondacks, New York. Source: George Wuerthner.

The exterior boundaries of the national forests in the Forest Service’s Northeast and Southeast Region enclose 48.6 million acres. Yet, only 25.6 million acres is publicly owned national forest land. Some 23 million acres (47 percent) of the land within the boundaries of national forests is not the nation’s forests. This land includes developments and settlements, but much of it is forested (from very fine to very clear-cut) or open fields that were once forested and could be again. No further action of state legislatures is necessary. See the Public Lands Blog post “National Forests in the Eastern United States: An Incomplete Legacy.”

Figure 16. A forest of “peckerpoles” that given enough time will grow again to be an old-growth forest. The colloquial term is most commonly used to refer to small trees that have come back after clear-cutting. The American East (and West for that matter) has vast numbers of peckerpole stands. Though some modern usage of the word is now associated with woodpeckers, its original and most common usage has nothing to with species in the subfamily Picinae. Source: George Wuerthner.

Bringing Back Beavers and Bats

Many of the natural openings in what were once vast and heavily forested landscapes were engineered by beavers. A keystone species (“a species which has a disproportionately large effect on its natural environment relative to its abundance”), the beaver is the only dam builder I like. An old-growth forest without beavers is like whiskey without alcohol or bread without salt. See the Public Lands Blog posts “Leave It to Beavers: Good for the Climate, Ecosystems, Watersheds, Ratepayers, and Taxpayers (Part 1)” and “Leave It to Beavers: Good for the Climate, Ecosystems, Watersheds, Ratepayers, and Taxpayers (Part 2).”

Figure 17. The official mammal of the states of New York and Oregon. Source: Government of the City of New York.

The federally endangered northern long-eared bat is acutely threatened by white-nose syndrome and wind turbines. It is also chronically threatened by habitat loss. While it hibernates in winter in hibernacula (mines and caves), during the rest of the year it “may be found roosting singly or in colonies underneath bark, in cavities or in crevices of both live trees and snags, or dead trees.” It prefers forest that is “a dense growth of trees and underbrush covering a large tract.” In other words, older intact forests.

Figure 18. The endangered northern long-eared bat. Source: US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Bottom Line: “If you have built castles in the air, your work need not be lost; that is where they should be. Now put the foundations under them.” —Henry David Thoreau (Walden, 1854)

For More Information

The following local organizations are among those in the vanguard of conserving and restoring mature and old-growth forests and wilderness in the American East:

• Northeast Wilderness Trust, Forever Wild video

• Save Public Forests Coalition

Figure 19. The literature on old-growth forests in the American East hasn’t been voluminous. I just read the hot-off-the-press-and-into-my-iPhone Nature’s Temples: A Natural History of Old-Growth Forests by Joan Maloof. Revised, expanded, and organized into bite-size chapters, this first-person account by the founder of the Old-Growth Forest Network is both a fun and an informative read. Source: Princeton University Press.

To Take Action

The Climate Forests Campaign (“Let Trees Grow: Protect the Climate”) is a broad coalition of conservation organizations leading the effort to achieve permanent administrative protection for the nation’s remaining mature and old-growth forests on Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management holdings.

Figure 20. Your humble author (right) visiting a very relic and very threatened stand of old-growth forest (200+ year-old trees) in the Cheat River watershed on the Monongahela National Forest. Source: Randi Spivak, Center for Biological Diversity.